There are cities that return the gaze: they do not yield docilely to the frame, but rather address those who contemplate them. They demand a way of seeing that does not reduce, that does not foreclose. Havana, in this Dossier conceived by the Cuban photographer Pedro Abascal, appears as an entity that observes, folds, and tenses; it refuses to become a mere stage or backdrop.

I have known Pedro since 2004, perhaps even earlier, from the time I began attending the exhibitions held in the dozens of galleries and institutions of Old Havana. I do not remember how we became friends; it seems we were so before we had properly met. Pedro is one of the great Cuban photographers of the past decades. Some of his photographs would make Cartier-Bresson raise an eyebrow.

Edvard Munch was one of the most finely tuned loudspeakers of his time’s spirit—the Zeitgeist. Dostoyevsky had been one before him, and Kafka would be another later on. He belonged to that rare class of human beings God seems to have assembled in haste—leaving the skull half-finished, the sutures open, the nerves exposed—those daemons of History chosen to transmit its message to humanity.

I met Mark at Annex Gallery, where he is working as an intern. Before I knew he made photographs, and therefore counted as an artist, I thought of him simply as someone who always needed a drink bottle within reach. One of those insulated flasks used by athletes or hydration fanatics that seemed to follow him more faithfully than his own shadow. I also knew, before seeing a single picture, that he supported Barça.

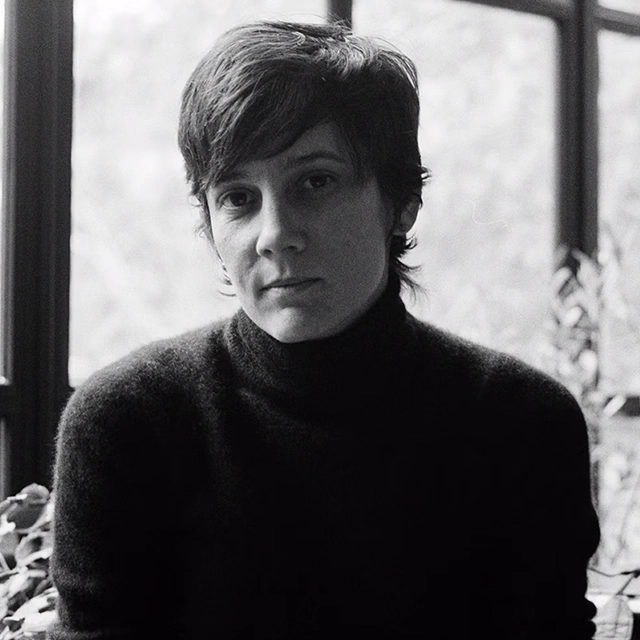

Talia Chetrit’s presence on the contemporary map of photography is not defined solely by the dismantling of her own intimacy. Born in 1982, trained in the analog tradition and in a visual thinking acutely aware of its own mechanisms, she has turned the domestic sphere into a territory of suspicion, especially in the series where she grazes—without fully yielding—the experience of motherhood.

The fall edition of The Paris Review features the work of two artists. Martha Bonnie Diamond is one of them. Born in New York in 1944, she died just two years ago, in 2023. She was among the most singular pictorial voices of her generation. For more than six decades she explored the city as a perceptual register. Rendering it recognizable never interested her.

Evelyn Sosa is a young Cuban photographer who has already left a subtle yet unmistakable imprint on the artistic ecosystem of the American Midwest. In 2024, she took part in Through a Stranger’s Eyes, an exhibition presented under the FotoFocus program. Coming from the Caribbean—and, more precisely, from Miami—she introduced a transnational conversation rarely encountered in these latitudes.

A few weeks ago, I visited Snakes and Ladders, the endearing exhibition by Sheida Soleimani at the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati. What struck me most was the meticulous care with which she constructed the settings that would provide a specific frame for the subjects of her photographs. I had the impression that she did not want to leave anything to chance...

The universe is a concert of patterns. Galaxies, solar systems, and planets share elements in common and others that set them apart. The same holds true for nations, cities, and communities. Cincinnati possesses a remarkable artistic community. As I gradually come to know its members, patterns begin to reveal themselves—those that identify them as part of a universal order, and those that distinguish them from others operating in different ecosystems, whether within the metropolitan circuits of Europe or in what is often called the Third World.