All images have been taken from the Fall 2025 issue of The Paris Review and from various sources on the internet.

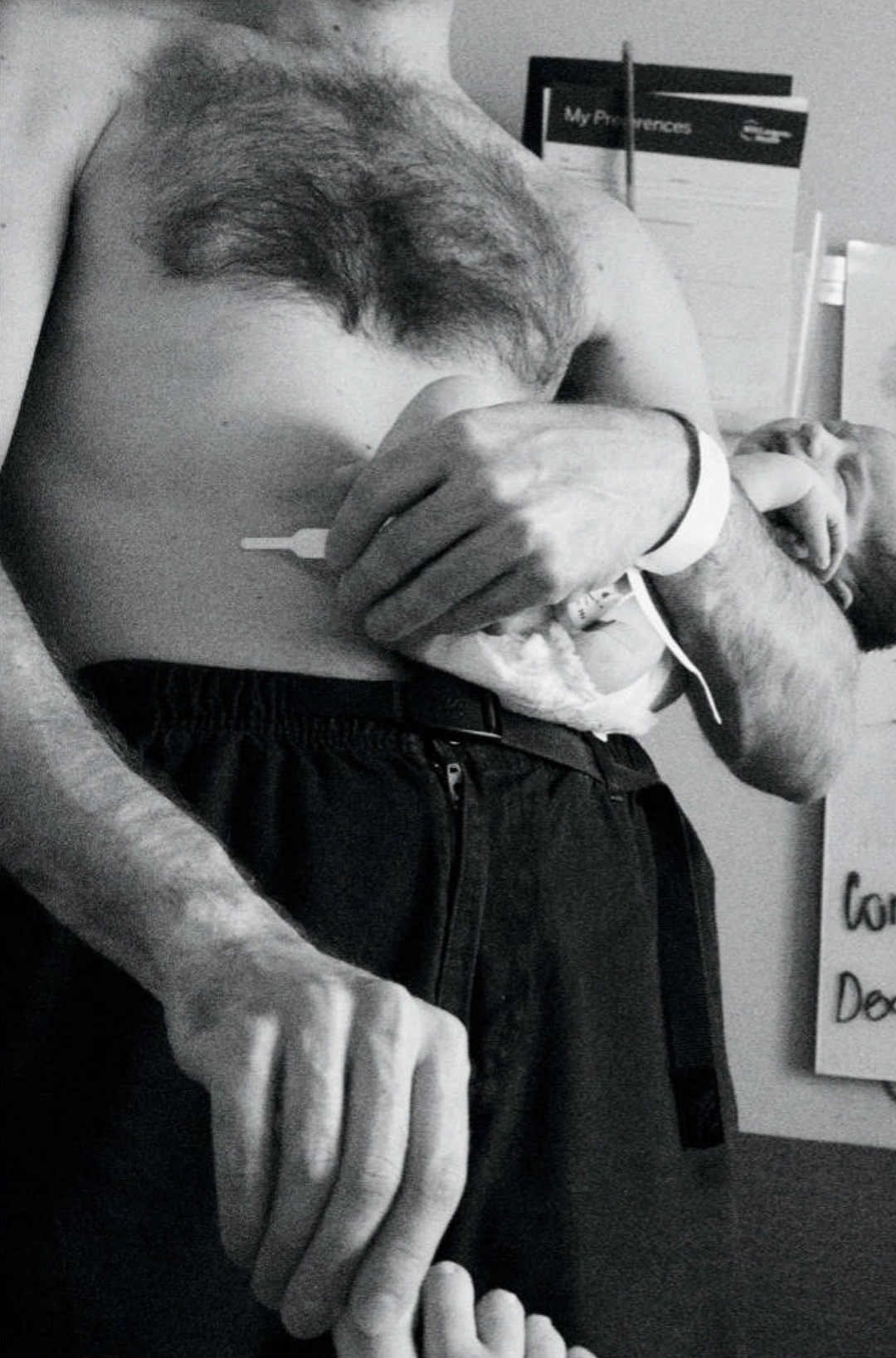

Talia Chetrit’s presence on the contemporary map of photography is not defined solely by the dismantling of her own intimacy. Born in 1982, trained in the analog tradition and in a visual thinking acutely aware of its own mechanisms, she has turned the domestic sphere into a territory of suspicion, especially in the series where she grazes—without fully yielding—the experience of motherhood.

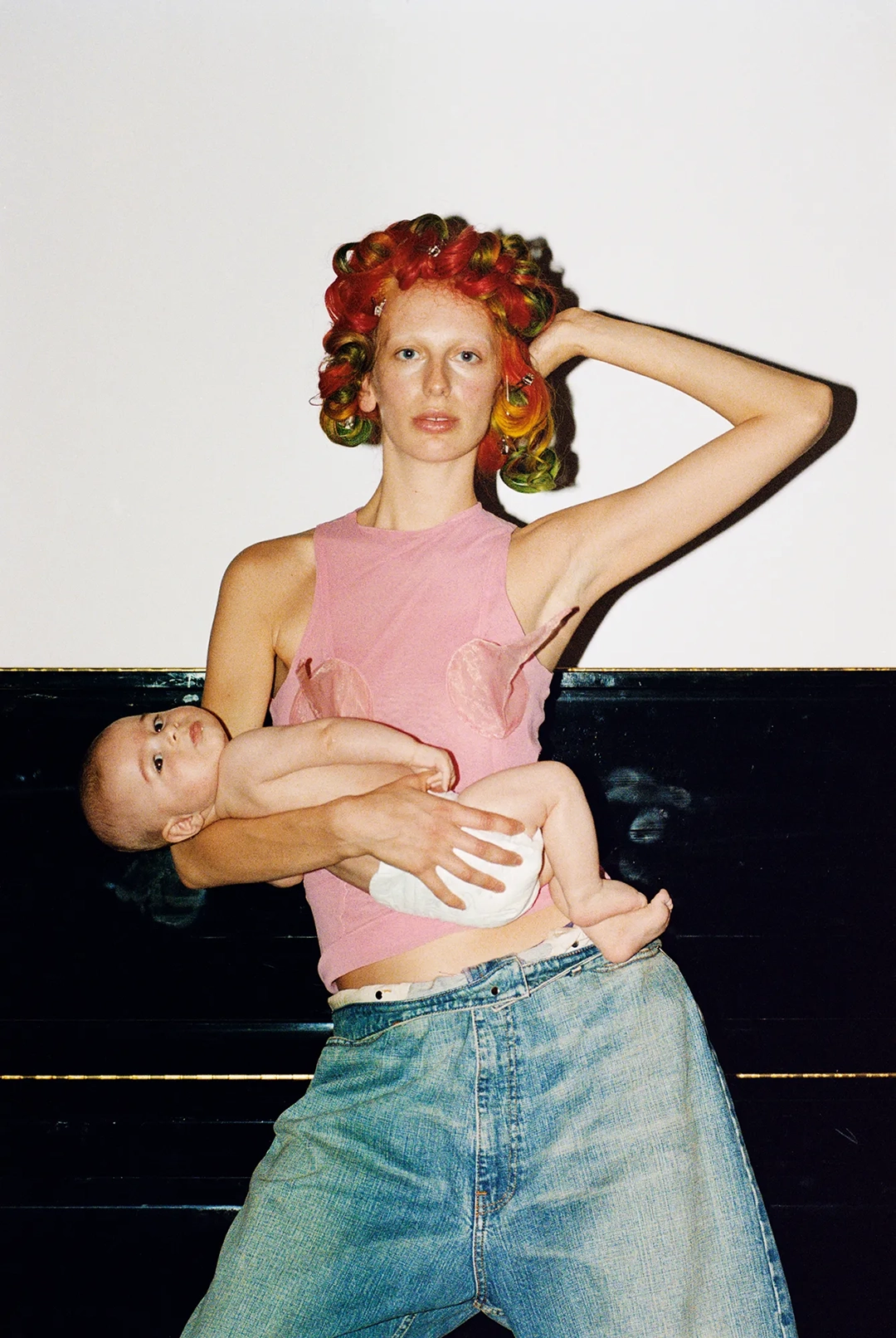

Her approach to the subject does not follow the usual iconography; it distances itself from sentimentality or any therapeutic register. In JOKE, the book published by MACK in 2022, motherhood appears more as a provocation than as a conceptual inquiry.

All images have been taken from the Fall 2025 issue of The Paris Review and from various sources on the internet.

Chetrit insists that her work is not “about motherhood” but about the taboo surrounding it. I am not entirely convinced that she, or whoever writes on her behalf, fully understands the meaning of the word taboo—a point that becomes evident after even a cursory analysis of her photographs. I read that she believes this “intimate process” is not anecdotal but a tool for delineating the range of “violent” images that culture is willing to tolerate.

I do not find much novelty in this. It happens all the time. Many artists intentionally expose images that challenge the psyche of elite environments, such as the cultural sphere. Perhaps this instinctive rejection is held in check by the tolerance granted by training. And yes, it is naturally intriguing to map the kinetics of these reactions in situ, if possible. Even more so when the attack—seen from a certain angle—targets the naïve cultural imaginary of motherhood.

All images have been taken from the Fall 2025 issue of The Paris Review and from various sources on the internet.

Many of these photographs, the rawest ones, stretch the limits of aesthetic tolerance. They exceed the threshold of symbolic discomfort and differential susceptibility, challenging the hegemonic iconography of care and tenderness. Put as bluntly as they themselves are: they focus on the vessel, the oven where a promise is baked.

How does the cultural system metabolize images that unsettle its affective homeostasis?

Probably quite well, because crossing boundaries—within the space expanded by the thirst for transgression and the fascination with the grotesque—is generally well regarded.

Motherhood may be illustrated with the image of a newborn in a mother’s loving arms. But also with the detailed photograph of a cesarean section. Within its imaginary, affective attenuation operates overwhelmingly. Negative features lose emotional weight. An eroticized breast has nothing to do with a breast used for nursing. Both can even be the same breast. If the goal is to undermine the bias of idealization, fine. The norm is to project potential, beauty, and luminosity while ignoring what is problematic, ambiguous, or uncomfortable.

All images have been taken from the Fall 2025 issue of The Paris Review and from various sources on the internet.

What would the natural mechanism be?

Cognitive dissonance managed through attraction. If we like something—or someone—and perceive some discordant element or signal, we automatically reorganize our perception so there is no internal conflict, so that what we desire preserves its ideal form.

Art can push this conflict to another level and trigger other responses. That is what we might call “an aesthetic experience of high intensity and a destabilizing effect.”

All images have been taken from the Fall 2025 issue of The Paris Review and from various sources on the internet.

In Chetrit’s case—and in many others—the material comes from her most intimate circle. She maintains a cold, intellectual distance from it. She assumes her life remains private while showing her own body. She is right. This is the foundation of her reading: intimacy as an act of construction, not exposure. Nothing in her work is spontaneous; each frame, each gesture, each shift in light responds to a conceptual intuition about the power—and the danger—of photography.

All images have been taken from the Fall 2025 issue of The Paris Review and from various sources on the internet

In that sense, her approach to motherhood seeks to insert it into a system of signs where the familiar becomes strange and the strange inevitably familiar. She is probably rehearsing a visual grammar for speaking about the body at a time when—especially women’s bodies—runs the risk of being consumed by reductive narratives.

Her contribution to the contemporary conversation, as the text at the beginning proposes, does not lie in showing what others do not show—which is common—but in daring to expose uncomfortable angles of an institution as sacred to society as motherhood. To declare it a “space” where the image can fracture, and where almost all joy pays a high price in pain.

All images have been taken from the Fall 2025 issue of The Paris Review and from various sources on the internet

Comments powered by Talkyard.