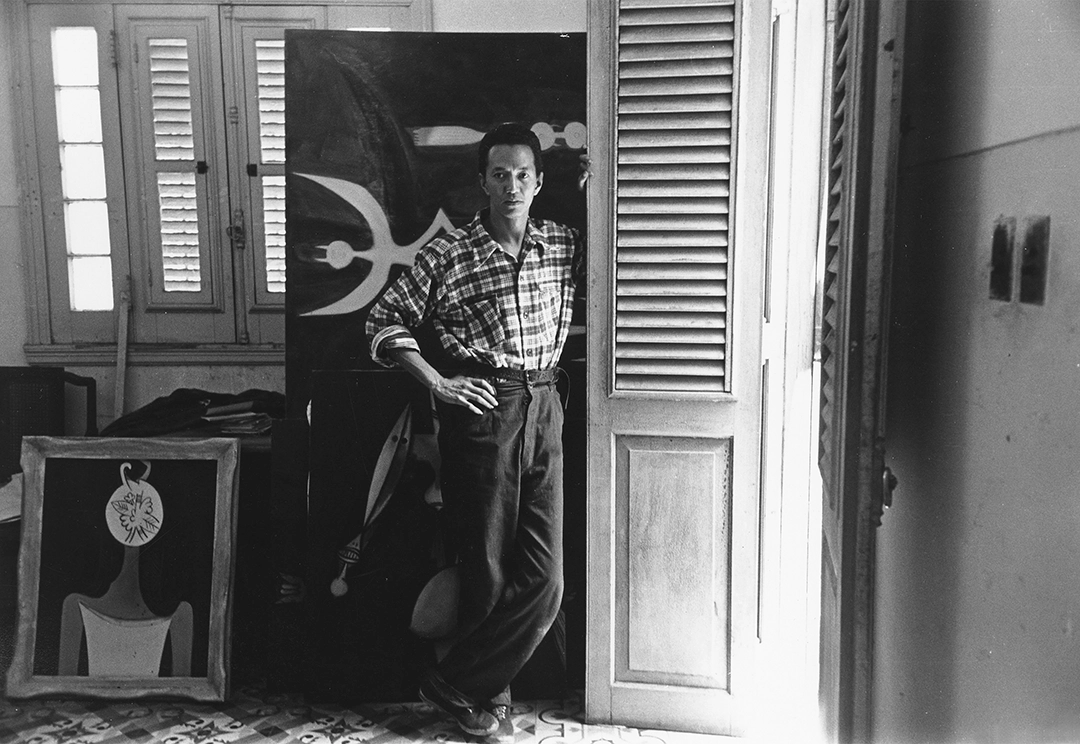

Wifredo Lam in his Havana studio, 1943 — MoMA.

What could I possibly say today about Wifredo Lam and the exhibition the MoMA has devoted to him? Little that hasn’t already been uttered—successfully or not—by the hundreds of critics and journalists who have read, interpreted, or merely circled around the curatorship of Christophe Cherix (David Rockefeller Director) and Beverly Adams (Estrellita Brodsky Curator of Latin American Art).

When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream has drawn many Cuban friends who live in New York and in other states. I doubt many traveled long distances expressly to see it, but I am fairly certain that nearly every specialist and practitioner of the visual arts honored the opening with their presence.

Every time I visited the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, I was captivated by the Lam works held there. My gaze evolved—as gazes do—with time, with experience, and with the knowledge I accumulated through my work, almost always tied to the visual arts.

For a time, I worked at the Wifredo Lam Center of Contemporary Art, designing materials about his biography and artistic trajectory. I also worked on his website, which never reached its final phase. In my homeland, beginnings abound, but endings are scarce.

Wifredo Lam fills me with a pale kind of pride. He is Cuban, but Cuba was for him a distant reference point, a comfortable thematic reservoir. The Cuba he imagined—at least as one can infer from his work—stretched beyond its natural boundaries, beyond its shores and reefs. I believe he could clearly perceive the root network that linked the island to its ancestral bases and its deeper identity structures. Something most of us think we see and understand. I am increasingly unsure that we do.

From its earliest years, the Cuban Revolution constructed an anticolonial narrative that cast itself as heir to the struggles of maroons and Black mambises. It wove Afro-Cuban history into the epic of national liberation. The almost ostentatious incorporation of African culture served not only internal aims: it bolstered the Revolution’s international projection, lending it symbolic prestige among newly independent African states and the broader Third World. It was a decisive moment in its anti-imperialist solidarity agenda. To bring the barrio closer to the Palace, the process was consolidated through the institutionalization of Afro culture and the creation of entities where the African component occupied a central place.

Before 1959, very few Cuban artists had integrated Black culture consistently into the visual arts. Wifredo Lam was practically the only one who forged an Afro imaginary that avoided both folklorization and exoticism. Amelia Peláez approached it only through ornament, and Mario Carreño did so only sporadically.

When the Afro became state policy, it was institutionalized, legitimized in academia, and placed at the center of the revolutionary narrative. That framework opened space for artists who engaged Blackness from an ideologically sanctioned position: Manuel Mendive, Flora Fong, Belkis Ayón, José Bedia, and the ritualist groups of the 1970s and 80s—all heirs to a cultural climate the Revolution had turned into program.

Wifredo Lam did not develop an Afro-Cuban imaginary during his formative years in Cuba; his early work, prior to 1923, reflects the academicism of San Alejandro and confines itself to portraits, still lifes, and conventional scenes devoid of Afro references. The iconography that now defines him—hybrid figures, masks, Afro-Caribbean mythologies—emerges much later, after nearly two decades in Europe. It was there that he completed his education and transformed his artistic vocabulary. He studied in Spain, aligned himself with Republican circles during the Civil War, and absorbed influences ranging from Goya to Expressionism. In 1938 he moved to Paris, where he met Picasso, Breton, and the Surrealists, entering into direct contact with the European avant-garde. That period—marked by war, exile, and experimentation—gave him the formal and conceptual tools that, upon returning to the Caribbean, would intertwine with the Afro-Cuban to define his mature language.

The Jungle, 1942-43. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Inter-American Fund. © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS)

He returned to Cuba in 1941. That renewed encounter with Afro-Cuban religions and rituals provided the visual and spiritual core that would radically transform his painting and make him the chief architect of an Afro-Caribbean language within modernism. He remained on the island for roughly a decade (until around 1951), developing both his Afro-Caribbean vocabulary and his surrealist practice. In general, the art world did not give him the attention he deserved, though writers and avant-garde artists recognized him immediately. His work arrived fully formed—international in register and endorsed directly by Picasso, the Surrealists, and the European cultural elite. Cabrera, Carpentier, and Fernando Ortiz understood that Lam was not imitating Afro-Cuban culture from the outside, but restoring a spiritual universe they themselves studied through anthropology, literature, and cultural history. His painting offered them the synthesis they had long sought: European modernism, Afro-Caribbean mythologies, and a profound anticolonial consciousness. For a Cuban avant-garde intent on defining what was “ours” without lapsing into folklorism, Lam was a gift from the heavens—a direct resonance with their inquiries and with the project of thinking Cuba from its African roots.

In 1951 he returned to Europe and settled between Paris and Albissola, where he worked with ceramists and broadened his material experimentation. During those years he exhibited widely in Europe and the United States, collaborated with poets and publishers on illustrated books, and consolidated his presence in the international circuit of Surrealism and late modernism. His work gained visibility, circulated in major museums, and formed part of numerous collective projects.

Once a celebrated figure, he returned to Cuba at the height of revolutionary fervor. He was received like a king returning from a Crusade. His friend Carlos Franqui, then a key figure in the revolutionary cultural apparatus, invited him to the May Day celebrations at the Plaza de la Revolución. When he asked questions, he learned that all the work he had left behind had been nationalized and transferred to the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes. They also informed him that he was now, more or less, Cuba’s official painter. He smiled, offered thanks, and returned to Paris, from which he missed Cuba with enviable comfort. He died there in 1982, without anxieties and without having to shoulder the marble weight of his historical persona.

Despite how little attention Lam paid to the young Revolution—anyone could see it—the regime could not afford to discard him as it had Celia Cruz, Olga Guillot, or Rolando Laserie. He belonged to the Pantheon of Giants, alongside Ernesto Lecuona and Bola de Nieve. In the visual arts, they could not erase Cundo Bermúdez or Amelia Peláez either—artists who likewise refused to trim their sails to the new winds. They represented exceptional symbolic capital for Cuban modernism and for the nation’s cultural projection abroad. In broad terms, revolutionary cultural policy oscillated between total cancellation of politically inconvenient figures and the partial, almost forced incorporation of those whose work was indispensable to sustain the narrative of Cuban cultural greatness.

So they managed to hoist Lam—without ticket—onto the Victory carriage; named the island’s most important contemporary art center after him; and commemorate his anniversary, in black and white, on the cultural page of the official press.

With figures of talent—athletes and geniuses of every sort—who aligned themselves with the Revolution, the exile, in the broadest sense, has shown little patience. And it is equally true that Cuba has thinned out or stretched itself, like a postage-sized pat of butter on a stale loaf spanning many miles, while the pride of being Cuban—again, in the broadest sense—lives its lowest hours.

Wifredo Lam in Cuba, 1950. Photo: Mark Shaw / mptv / eyevine. Artwork: © Wifredo Lam, DACS 2023

Comments powered by Talkyard.