Image illustrating the original text in The Washington Post

In The Climate of Art Collecting, Christopher Cameron examines how extreme weather events are radically reshaping the economics of the art world. In the wake of recent fires, hurricanes, and floods, private collections, galleries, and studios face losses without precedent, raising troubling questions about the fragility of cultural heritage and the limits of insurance. The piece shows how climate change is forcing collectors, insurers, and museums to rethink preservation strategies and their own responsibilities in a market growing ever more vulnerable.

What follows is a personal reflection on what I believe to be most significant.

Art is created—or acquired—almost always with a shared purpose: to be seen, to enter into dialogue with others. There are, of course, artists who, out of modesty, conviction, or sheer mystery, prefer not to show their work, but such cases are rare—especially when we speak of artists of true talent. And there are collectors who, once a piece is theirs, hide it away as if possession outweighed the act of sharing. Thus emerges the art of shadows: works that exist in secret, that breathe in seclusion, far from the eyes of the world.

Throughout history, the fragility of the art object has condemned it to a cruel impermanence. Thousands of extraordinary works have vanished in wars, looting, fires, or floods. Art, which so often resists oblivion, has implacable enemies: fire and water—opposites in essence, allies in destruction.

I too was, for years, a very modest collector. Not out of luxury, but affection: each work that came into my hands arrived as a gift, an act of kindness from artist friends. Some pieces were beautiful beyond measure. None faced a natural disaster, but they did encounter something far more patient and infallible: time.

Most of them survived, not because I knew how to preserve them, but because they managed to escape me. I lacked the conditions and the means to protect that small treasure entrusted to me. And yet many of those works remain close by, still alive, still speaking to the world—but no longer from my walls.

My personal story is minor in the grand tally of losses and attachments. But I bring it up because The Washington Post published today an article on the subject. The text, titled The Climate of Art Collecting. Extreme weather is shaking up the economics of the art world, is longer than a Monday.

Image taken from the print edition of The Washington Post

I read it as if climbing a hill. And with great pleasure I distilled it into a few paragraphs to share with you—friends, colleagues, people who either row against the current or so often languish in infernal queues:

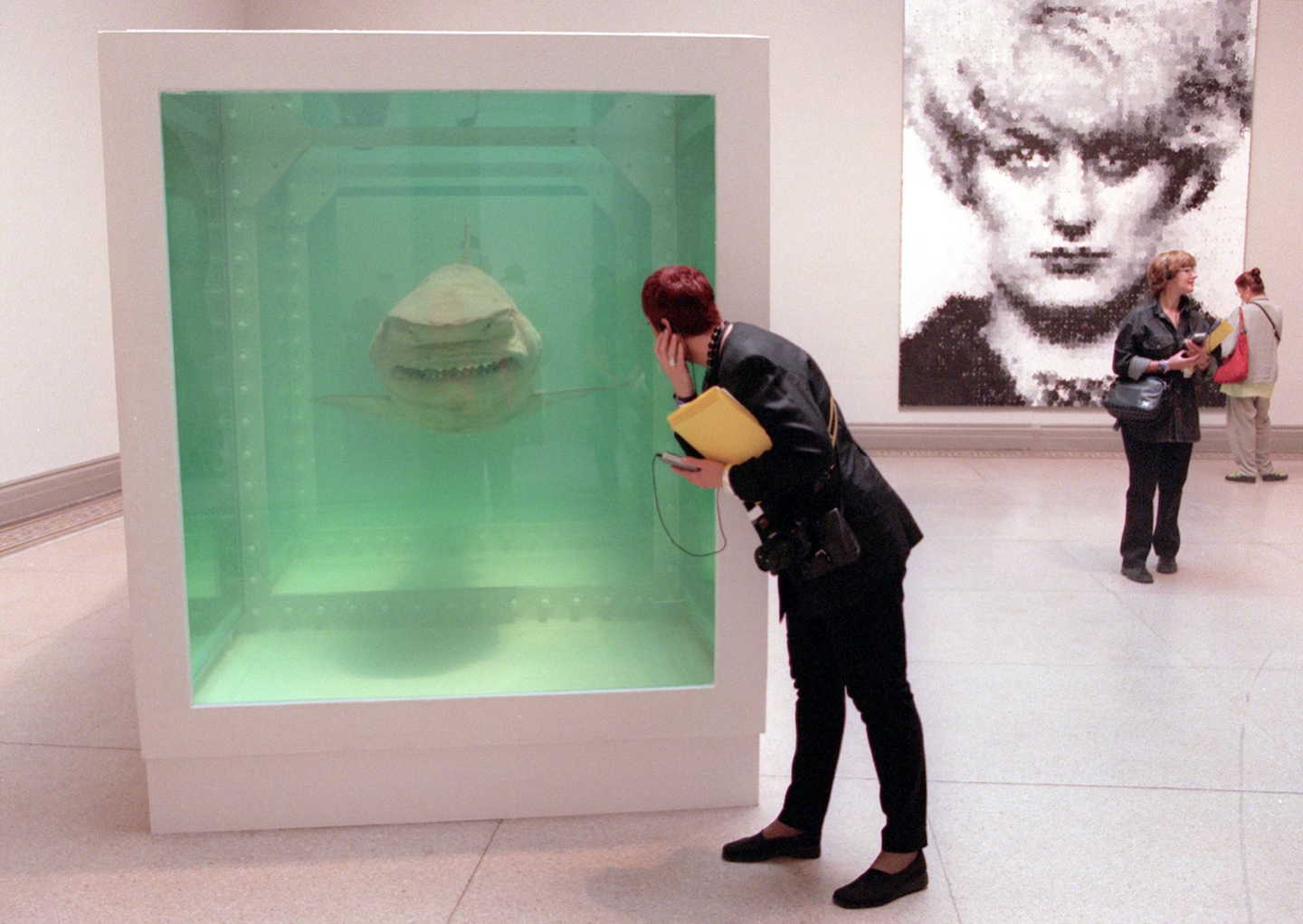

The wildfires that ravaged Los Angeles destroyed not only mansions and palm trees; they also consumed an essential part of contemporary cultural heritage. Ron Rivlin, collector and gallerist specializing in Warhol, saw his home reduced to ashes along with more than 300 works of art, including 30 Warhols and a monumental spin painting by Damien Hirst. He saved three canvases, the ones that fit into his car, while the fire advanced relentlessly. And like him, many others have remained silent. It is said to be the greatest loss of art since World War II, but no one knows—or will admit—just how many pieces were truly lost.

This tragedy exposes a deep fissure: the United States has no centralized art registry. No cadastre, no transparency, no coordination between insurers, museums, and collectors; the system floats in ambiguity. What can be done when the cultural value of a work burns alongside its monetary value? Cameron’s article does more than document disaster; it asks uncomfortable questions: is it ethical to keep masterpieces in regions prone to climate risk? Who decides what deserves to be saved?

Some, like the Getty Museum, survived thanks to rigorous protocols: clearing brush, constant irrigation, trained brigades. But in the private sphere, solutions range from Swiss vaults to replicas hanging in luxury homes. Isabelle Bscher recounts how some clients prefer to store the originals and live with copies; others, like Bill Gates, favor digital screens that rotate virtual works. Art as symbolic presence rather than material object seems to be a growing trend among those for whom wealth itself becomes a burden.

In this new landscape, the figure of the collector is changing. Hedges, another voice in the article, puts it bluntly: the “art prepper” has been born—someone who amasses not only works but also protection systems, private jets, and bunkers built to withstand meteor strikes. Because if fire can reach Pacific Palisades, it can reach anywhere.

This story is a warning, a stark reminder of art’s place—and its fragility—in an age of climate threats. Perhaps it is time to rethink not only how we protect it, but also how willing we are to share it with the world before it disappears.

Ron Rivlin, 51, art collector and owner of Revolver Gallery, poses for a portrait at his gallery in Los Angeles on March 17. (Philip Cheung/For The Washington Post)

Comments powered by Talkyard.