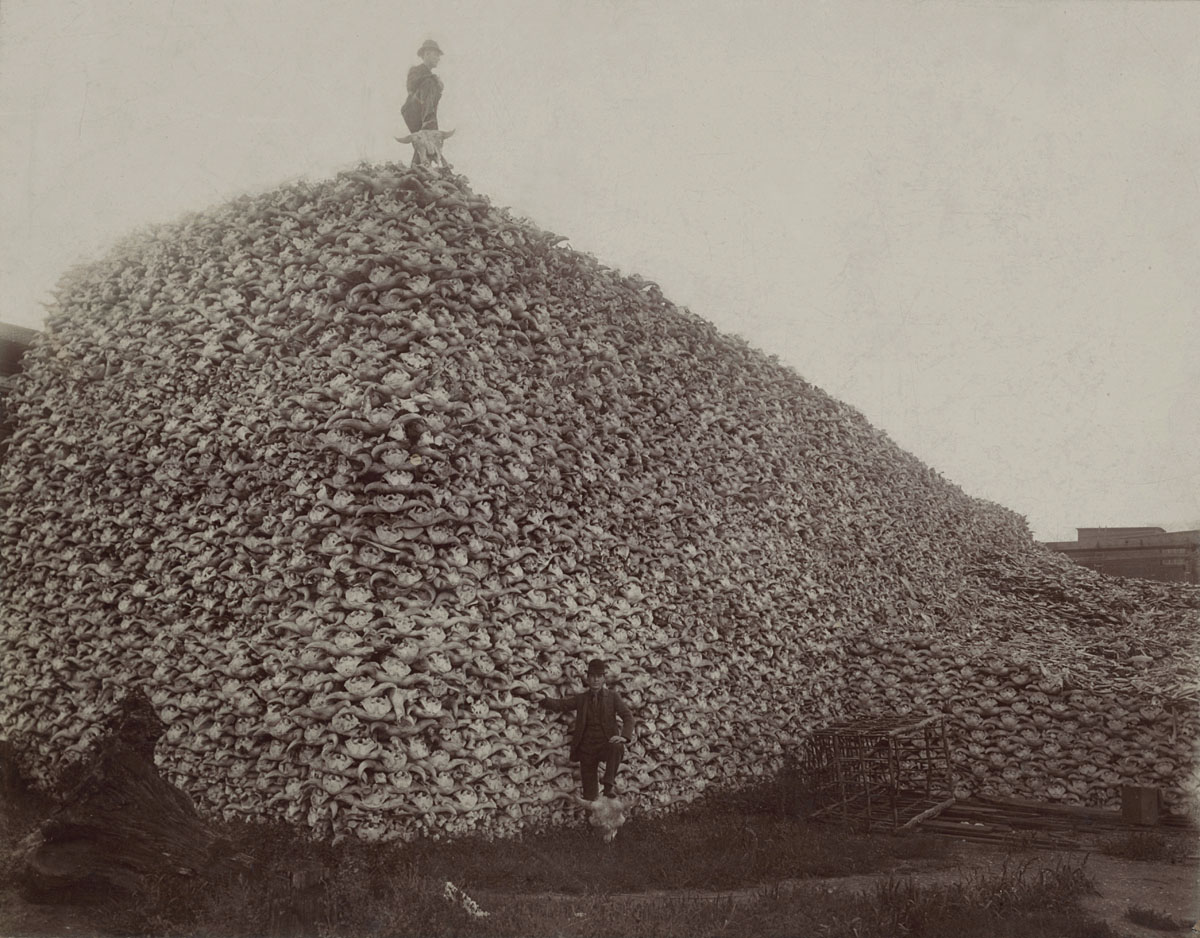

A mountain of bison skulls awaiting to be ground into fertilizer. Some sources date the photograph to around 1892, others to the mid‑1870s.

Don’t bother. There was neither a penultimate nor a last. That story was a lyrical invention by James Fenimore Cooper to captivate the eager readers of the early nineteenth century. The tribe, much diminished—now part of the Stockbridge‑Munsee—lives today in Wisconsin, to the west of the Great Lakes, enduring the heavy snowfalls the region bestows for much of the year. And what do they do? They run casinos, persistently demand the restitution of their lands, and in their spare time, pass on their culture to the new generations.

The full‑blooded Mohicans once lived in the Hudson Valley region, in what is now the state of New York. Their original name, Muhhekunneuw, means “people of the waters that run swiftly.”1 They were not given to many words. Beyond their linguistic austerity, they farmed, fished, and hunted. They had a taste for protein and detested the midnight gnaw of hunger. They traded furs with the earliest Europeans—English and Dutch. Within months, they were declared persons and drawn into a brief conflict.

But let us, for a moment, take Mr. Cooper at his word and imagine there truly was a lone surviving Mohican. How did we lose the rest? Through battles with other tribes, through the ravages of smallpox, through relentless colonial encroachment. One decisive factor, beyond doubt, was the disappearance of their totem animal: the bison.

This majestic herbivore is now an emblem of North America. Monumental in size, bound to the continent’s first peoples since time immemorial, it was regarded as a sacred being. It was received as the greatest gift the gods could offer: meat and fat for sustenance, hides for clothing and shelter, bones for tools and weapons. For the tribes of the Great Plains—the Lakota, Cheyenne, Comanche—it was the axis of life itself. More than flesh, it was spirit. A creature of supreme purity; and among them, the albino or white bison was revered as a celestial incarnation, descending to bring abundance, strength, and resilient hope.

This profound bond sealed their fate. The European settlers quickly understood that without the bison, the tribes would have no choice but to move on. The cruelty lay in the intent: to strip them not only of their sustenance, but of their identity, their customs, their very culture.

The U.S. government encouraged the slaughter of the bison to unimaginable levels. In the span of half a century, their numbers fell from nearly sixty million to fewer than five hundred. Their bones were crushed for fertilizer, their hides shipped to Europe, their flesh left to rot.

Was hunting truly the main cause of the near‑extinction of the American bison? Some doubt it.

The image that prompts these notes was taken, according to some sources, in 1892 at the Michigan Carbon Works in Rougeville, Michigan. It captures a pivotal moment: the American expansion westward. It shows a man standing nonchalantly atop a mountain of bison skulls. The casual pride of his stance betrays a total disconnection from the ecological devastation at hand—and a foolish, self‑satisfied pride. There was a time when even refined ladies were invited to shoot into massive herds from the comfort of passing trains, purely for the perverse thrill of watching those bewildered giants collapse. Hundreds each day. This, they called progress. In its name, and in the name of industrialization, driven by their hunger to capitalize on every natural resource, settlers enacted an unprecedented campaign of subjugation upon the wild. For the first time in the planet’s history, a single species imposed such an obscene asymmetry upon nature itself. Born predators, they annihilated everything—humans, cultures entire.

It is idle to judge the nineteenth century with a twenty‑first‑century mind.

Let us not lose perspective either: it would have been impossible to wipe out sixty million bison with light firearms alone. Millions—indeed, the majority—perished from diseases introduced by European livestock. The same fate befell many of the great Indigenous populations of the Americas. That does not, however, diminish the deranged, blood‑driven frenzy of the white colonizers.

Now let us attempt one last exercise: to imagine what the proud tribes of the North once witnessed five hundred years ago. Consider that a full‑grown bull bison reaches almost three meters in length, two meters high, and can weigh up to 2,600 pounds. A typical herd could stretch thirty kilometers long and half a kilometer wide. Feel the ground tremble under the pounding of thousands of hooves, hear the endless lowing, the thunderous roar that carried far ahead of them, the rising cloud of dust trailing these boundless rivers of life as they coursed across the plains. Far away, the hunters’ hearts beat faster—torn between reverence, hunger, desperation, and joy. Warriors and hunters who, in their deep understanding of the sacred balance of living things, grieved as they took the soul and flesh of an animal they considered a brother. A spectacle no human being will ever witness again.

1I am still unsure what, in fact, flows swiftly—the water… or the Mohicans?

Postscript

1 – The original photograph is kept at the Detroit Public Library, part of the Burton Historical Collection, which preserves documents and images significant to Detroit’s history and its surroundings.

2 – The bison have recovered. Their numbers are estimated at around half a million, mostly on private ranches. Many are crossbred with domestic cattle, resulting in hybrid bison. Yet there are about 25,000 genetically pure bison grazing in protected reserves, many within Yellowstone National Park.

Comments powered by Talkyard.