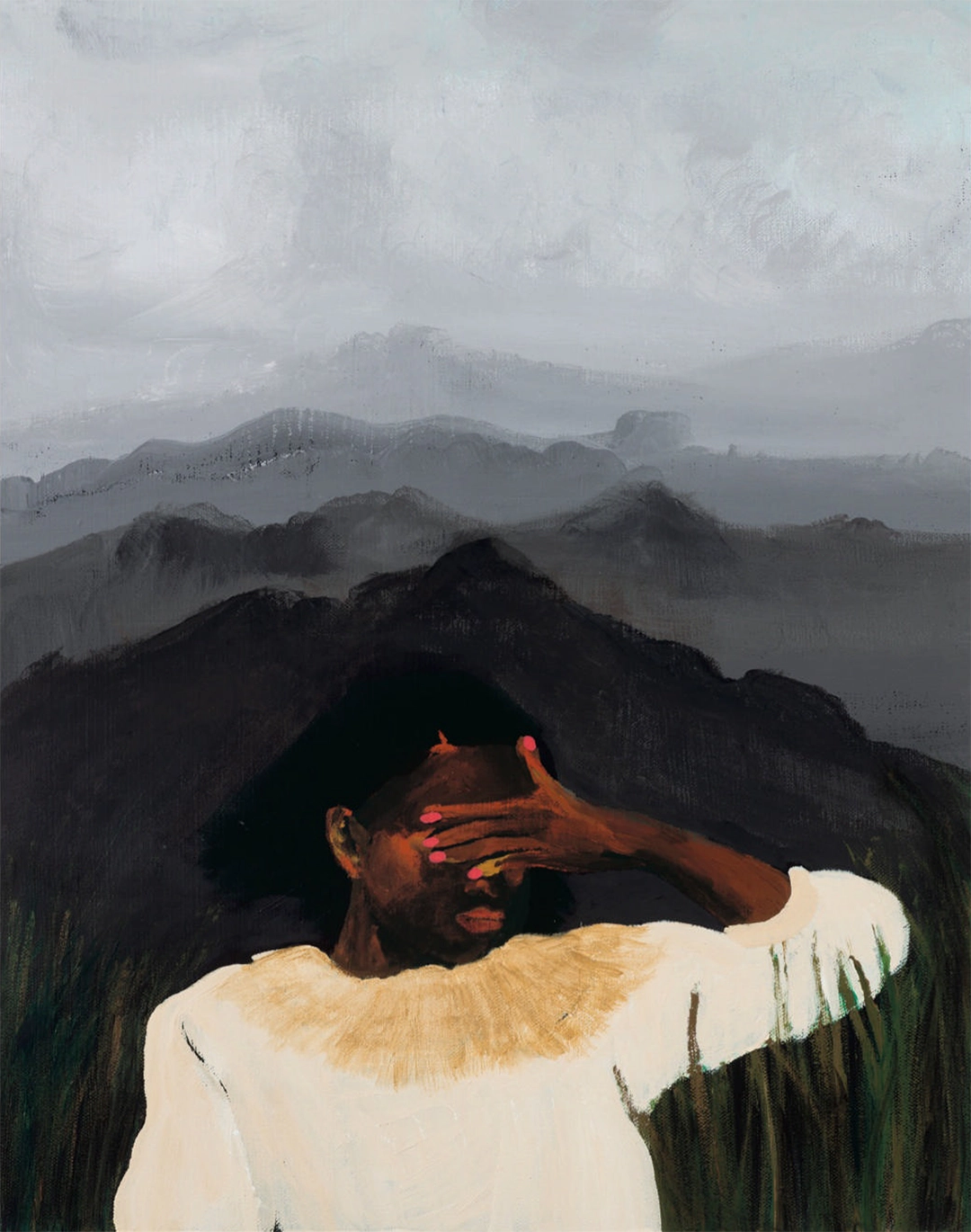

Prophetic, a painting by Danielle Mckinney, whose work is on view this month at the Rose Art Museum. Harper’s Magazine. November, 2025

Day after day, I browse through a handful of publications that, either in their entirety or in their cultural sections, comment on the most significant events within the visual arts. They form the main source of my modest archives. At times I come across striking images that merely illustrate an article; fortunately, when the magazine is a serious one, the caption provides all the essential data. Yet beyond the excellence of the work itself, it’s worth asking, every so often, whether—as illustration—it’s truly a fitting choice.

In this case, the text is a work of fiction by Olivia Laing, reconstructing how Pier Paolo Pasolini and his crew carried out the pre-production of Salò, in search of a language of confinement where the symmetry of the frames was essential to seal off both visual and mental space. They go scouting for locations, and that making-of becomes a moral meditation. The Republic of Salò as an unfinished trauma; mise-en-scène as closure; costume as evidence and accusation —a monochrome palette, hierarchies of domination—; the layers of complicity that enable horror; and the film as an exorcism of private and political wounds. It is a past that terrifies—and one our present has yet to dispel.

In Laing’s story, the character Danilo accuses the system of being sustained by everyday complicity. Many of us “look the other way” at times, and with half-closed eyes become passive participants in horror.

That is why I find Prophetic, by Danielle McKinney, an uncannily precise illustration—almost too precise, in its emphasis. Its monochrome scheme with a single chromatic accent mirrors the “drained of color” vision of Salò; its hazy landscape and steady frame produce enclosure and suspended time. The white dress gathers the gaze and turns clothing into a locus of meaning. It does not adorn; it argues. Within Laing’s framework, costume functions as both accusation and testimony, so that white becomes a cipher for the image’s ethical dimension. At the same time, by covering her eyes, the figure interrupts the reflex circuit of spectatorship—face, gaze, appropriation—drawing a boundary, withholding availability, and deactivating the gratification of looking without consent. That refusal imposes an ethical distance and forces us to reconsider what it means to look—and what it means to look away.

Still, what drew me most to the image were its formal values. The figure dominates the foreground, her back turned to her surroundings. The landscape—European in appearance, yet more likely a mental than physical space—perverts facial recognition, externality, and notoriety, hurling us directly into her interiority. The gray and black mountain ridges, almost monochrome, stratify into bands reminiscent of Zurbarán’s darkest tones and the light narrative of Vermeer. They function best as psychic topography, imposing distance, foreboding—prophetic—and silence. This chromatic economy is typical of McKinney, who often lets the figure emerge from darkness to reveal her psychology. The nails provide the brightest note of color—warm accents that would have pleased a color glutton like Matisse. In that contrast I read the tension between an inferable inner storm and a dry, categorical gesture of refusal: exterior calm, latent intensity.

Danielle McKinney by Pierre Le Hors, Vogue

Danielle was born in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1981. She holds a BFA from the Atlanta College of Art and an MFA from Parsons School of Design. During the pandemic she left photography to devote herself entirely to painting. Her work has been shown at Marianne Boesky Gallery (New York) and Galerie Max Hetzler (Berlin/London). Tell Me More, at the Rose Art Museum (Brandeis University), is her first solo museum exhibition in the United States. Her women—mostly Black—appear in states of rest, introspection, and self-care, in counterpoint to their historical hypervisibility as function. Curatorial texts have framed her work as a narrative of resilience—but then, what isn’t today a narrative of resilience?—of beauty and autonomy in Black womanhood. Their serenity invites us to breathe alongside them, legitimizing their right to rest and to interior life.

A remarkable work, and a splendid use by Harper’s Magazine’s art direction and design—could one expect less from the oldest continuously published general-interest monthly in the United States? Hardly. Does this digression take us away from the initial question? Perhaps. But if there is one thing neither Salò—nor the image that accompanies it—allows, it is to look away. Faced with the signs of a return to inhuman and shameless times, we cannot turn aside; least of all, cover our eyes.

Comments powered by Talkyard.