Go to English Version

Go to English VersionIn the early years of the eighties, while I was slogging through junior high, two ravishing Hungarians crossed my path. Katalina Soós shot past at such speed that I could only glimpse her contours through a pocket telescope. The other, Szonja Török, struck me with the same force with which the Tunguska meteorite flattened the remote Siberian taiga. Hungarians were something else entirely. You could tell by their avant‑garde hairstyles, by the freedom and self‑assurance with which they moved. They took what they wanted without asking. From the banks of the Danube, János Kádár governed his people with a soft hand. Aligned with the Soviet Union—as he could hardly avoid—he maintained a policy of political and economic openness that somehow made Hungarian women more… open.

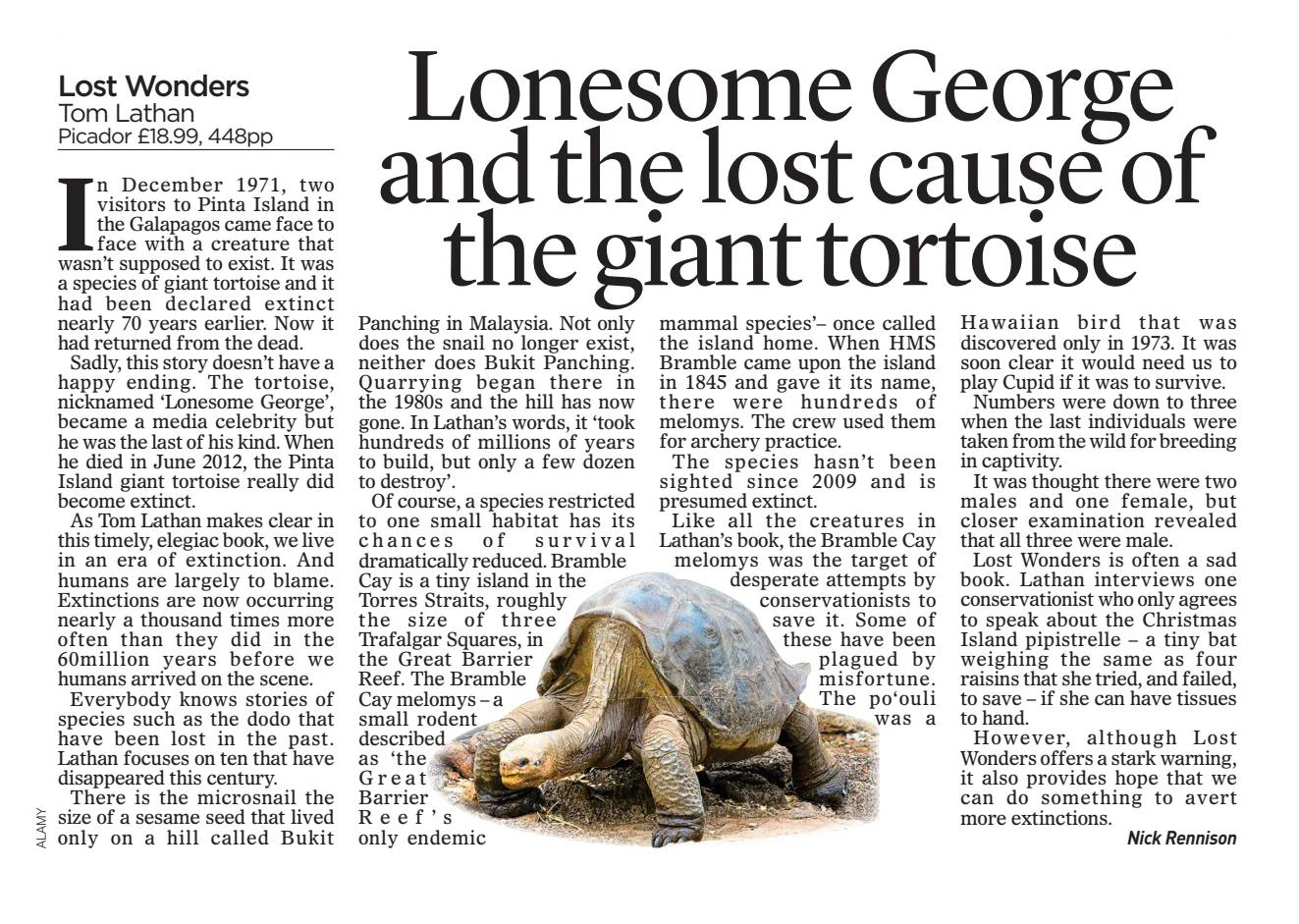

On a mild December morning in 1971, a Hungarian—microbiologist József Vágvölgyi—wandered along one of the beaches of Pinta Island in the Galápagos, accompanied by the Briton Peter Pritchard. They were engaged in the scientific version of a treasure hunt. Any fleck of gold, a ring, something left behind by some drunken pirate at the dawn of time. What they found was astonishing: the last known specimen of a giant tortoise, long believed extinct since the turn of the century. The surprise was immense, even to the international scientific community. Peter was already known for his work conserving endangered turtles. The Hungarian was virtually unknown. Yet there he stood, and we cannot scrub him from this tale of Hungarians.

The tortoise—a male—was christened Lonesome George. News that a specimen from the Pinta Island subspecies still lived was of enormous importance to conservation efforts in the Galápagos. It inspired the creation of a National Park and a frantic movement to breed the species. But velocity and breathtaking acceleration are not in the nature of tortoises, no matter their size. And although Lonesome George became a celebrity—long before social media—he left no descendants.

On Lonesome George’s weathered face one can see the deep furrows carved over centuries by sun and silence. His dark, moist, and gleaming eyes hold the memory of a world long before our own. They hide secrets that will never be revealed. The jaw—barely curved in a motionless expression—presses the infinite patience of a sage who watches the passing of men without flinching, knowing that life is slower and vaster than we can ever grasp.

In a luxury suite at the Charles Darwin Research Station in the Galápagos, George received numerous lady visitors, native to Isabela Island. These little tortoises in bloom shared certain genetic traits with George; they arrived with glossy shells and coral‑sick teeth. George paid them no heed. Others—certainly none of giant stature—lingered for days, yet the imperturbable one resisted all temptation.

George finally died in 2012, and the subspecies Chelonoidis abingdonii was declared extinct.

What does this text inspire in me?

The image, of course. That immense weariness you sense in the extinct one, the last, the unrepeatable.

It never occurred to anyone to try with a Hungarian turtle, say the European pond turtle, the only one native to the region. There’s even another, a red‑eared slider (Trachemys scripta elegans), smuggled in by traffickers and now displacing the native species with its cheeky, uninhibited ways. Perhaps George needed something more: the lilting sway of Brahms’s Hungarian Dance No. 5… we shall never know.

Let me be clear: despite my age and my name, this is no autobiographical allegory. It is not a mating call, nor a courtship cry.

And if by chance Szonja Török happens to read these lines, let her know that…

The last known specimen of the Pinta Island giant tortoise (Chelonoidis abingdonii), photographed at the Charles Darwin Research Station, features in Nick Rennison’s review of Tom Lathan’s book Lost Wonders (Picador, 2024), published in a British literary supplement as a poignant emblem of species that vanished before our eyes.

Comments powered by Talkyard.