Go to English Version

Go to English VersionBy the late nineteenth century, a group of Japanese statesmen had decided they’d had all the shogunate they could reasonably endure. However beautiful the swords and scabbards, it was time to catch up and tune themselves to the rest of the world. Japan had to modernize and find other uses for the wheel. Those visionaries from the domains of Satsuma, Chōshū, Tosa, and Hizen became the architects of the new state. The decisive figures, as I see them: Ōkubo Toshimichi (Satsuma), one of the most influential leaders and principal architect of political and administrative reform; Kido Takayoshi (Chōshū), crucial on the cultural and intellectual front, who pushed through the abolition of the feudal system and sent the first students abroad; and Okuma Shigenobu (Hizen), founder of Waseda University. None of this would have been possible had Tokugawa Yoshinobu, the last Shogun, not chosen to surrender in order to avoid civil war. Emperor Meiji —who, like any emperor, practised the imperial art of looking— became the symbol of national unity and of the end of the shogunate. His restoration marked the formal return of power to the throne.

These illustrious Japanese knew perfectly well that no one in the world sharpened knives quite like they did, but that was no longer enough to compete with the Western powers. They had spent too long contemplating —politically speaking— their own Nipponese navel, and the world had overtaken them on the right with dizzying speed.

After the First World War, Japan sent its most polished and self-contained sons to study and dissect the habits of their German, French and American counterparts. Western artists were, in turn, invited to Japan to teach their techniques. The traffic in both directions sparked an unprecedented fascination with “the modern”. Modernity itself became a value, and with it came the subjective, the abstract, and a taste for gazing into the darker abysses of the human psyche.

As Western magazines and illustrated books arrived, urban Japanese discovered Art Deco, Hollywood films and the great touring dance companies. Confronted with the kinetic frenzy of those foreign dancers, classical Japanese performers realised that their own gestures looked immobilised, subtly spasmodic, calibrated by ancestral geometries. They understood that dance could tap directly into carnality and vitality, into pleasure as the ultimate end of experience. And they recognised that what they had been doing since the Nara (710–794) and Heian (794–1185) periods resembled, more than anything, a bow to the puckered tastes of feudal lords rather than to any primitive spirit of expression. There was no way for their choreographic vocabulary to converse with the world in front of them without being dismissed as a historicist exercise.

The new languages that began to dominate the national stage did not progress much beyond suffocated imitations, disconnected from Japanese sensibility. These were bodies that, in Hijikata’s words, “behaved like tourists within themselves”.

It is in this climate that Tatsumi Hijikata, together with Kazuo Ohno —in a country battered by devastation, censorship and the grinding tension between tradition and modernity— founded butoh, a radical break with Western ways of conceiving dance. Initially called ankoku butoh, “the dance of absolute darkness”, it was a declaration of rebellion, not only corporeal but spiritual. And although it traced a path back to rituals deeply rooted in Japanese culture, it also drew heavily from German Expressionism and the European avant-gardes. The result was something wholly new: raw, extreme choreographies that resonated with the archaic memory of the Japanese body. A choreographic alphabet that embraced the grotesque, the slow, the visceral and the marginal to confront —in a distinctly Japanese way— historical pain and the strange beauty that germinates from defeat.

Onstage, those bodies seem to be occupied by impatient spirits, by invisible presences that give flesh to memory. They connect organically to corporeal traditions born of the animistic, the rural and the ceremonial. They open space for the duality between life and death that still pulses in remote Japanese villages and runs through the entire culture. This is the aesthetic of yūgen —the mysterious, the implied— and of wabi-sabi, that exacting attention to the imperfect and the perishable. These are the traditions that embrace ritual darkness, emotional restraint, the intensity of the minimal gesture.

The result is a theatricality of extraordinarily fine, almost timeless beauty.

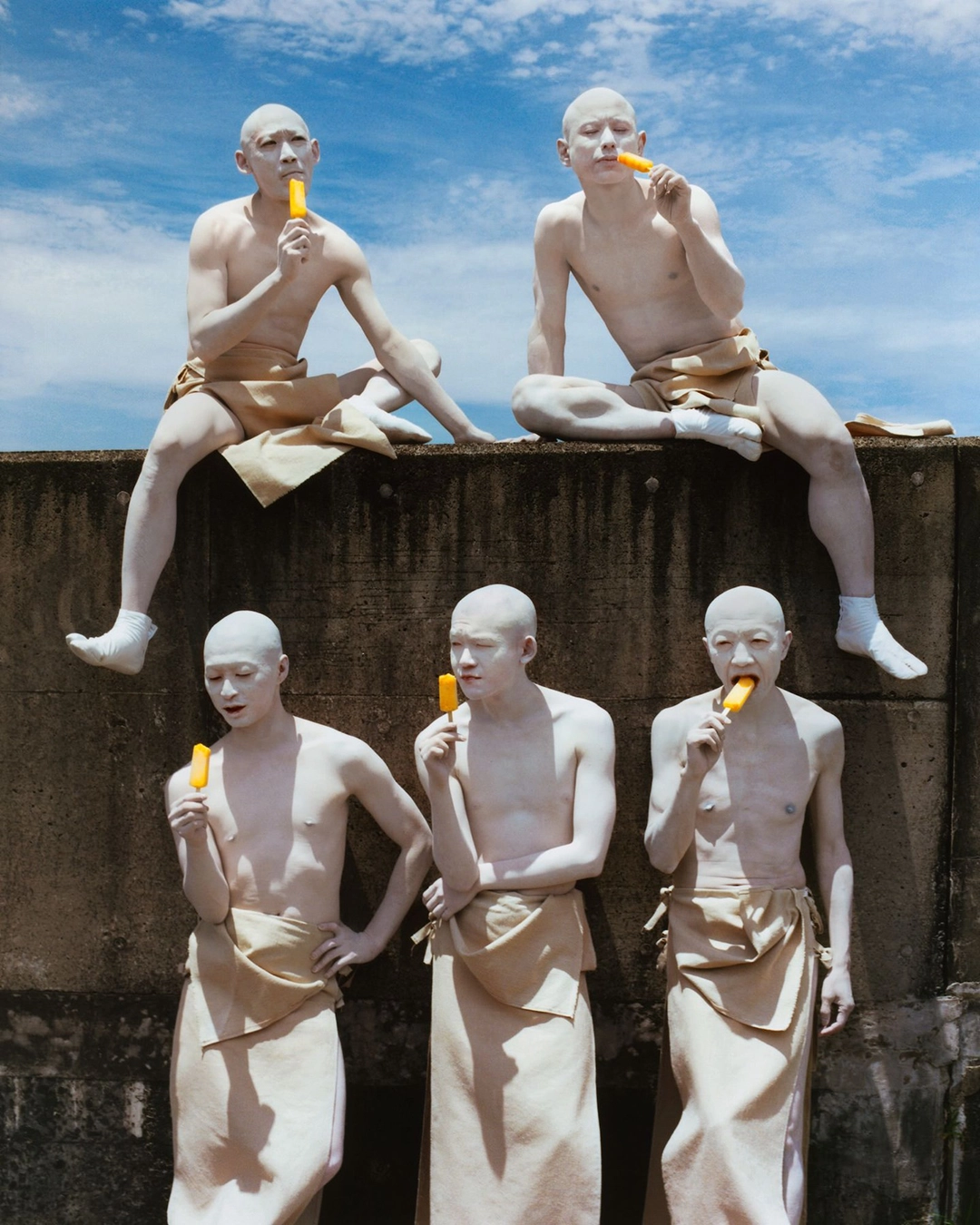

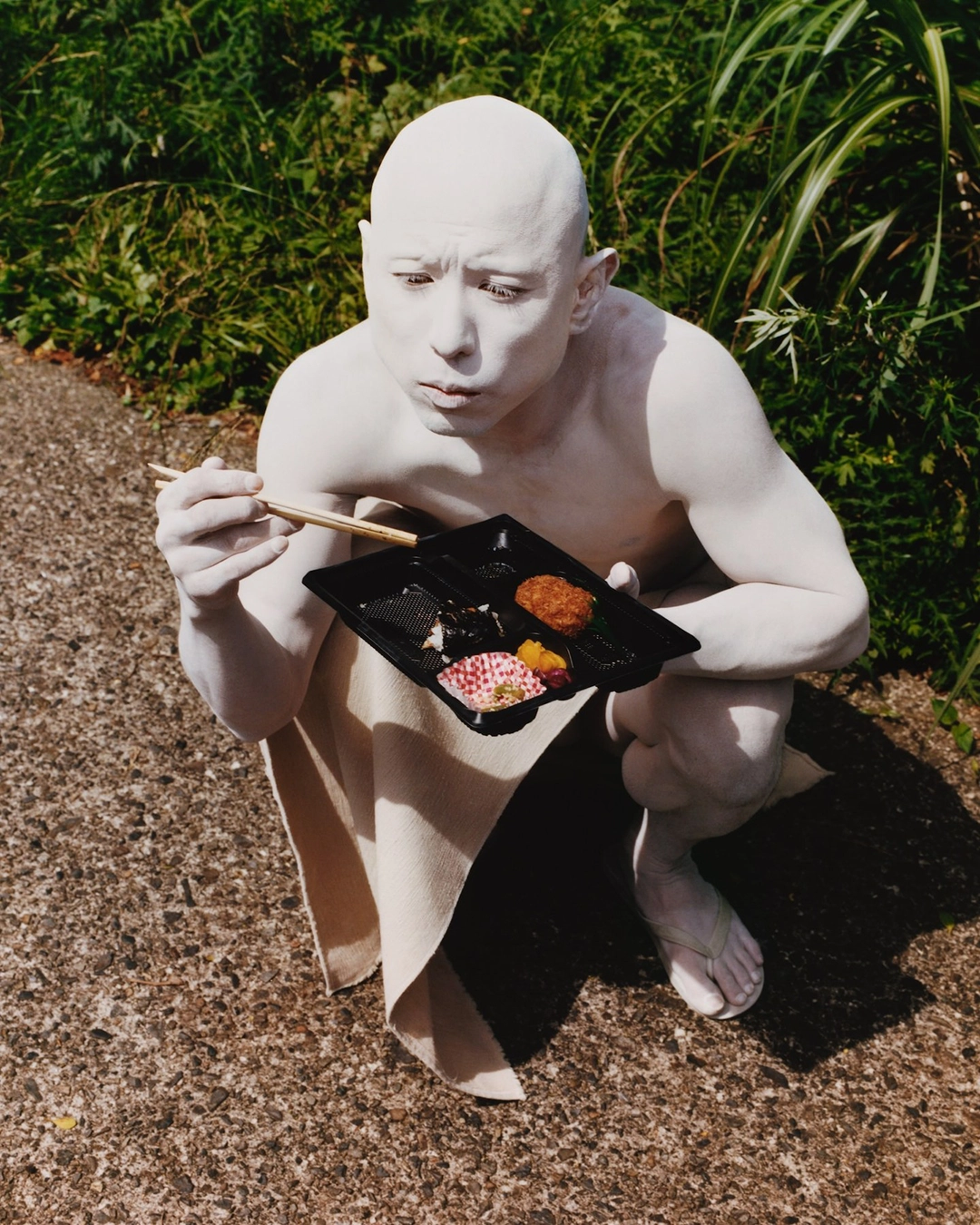

It is this beauty that British photographer Tom Johnson encounters almost by chance, through his friend, stylist Mari Ohashi. She ushers him into that universe of painted bodies and shaved heads, where intensity seems to rise from strata older than thought. Visually, it is an ambush: an unexpected discovery that refuses to let go. What began as a simple magazine editorial soon overflowed its frame. The images demanded more room. First they became an exhibition. Then they insisted on becoming a book.

Over the course of two trips, armed with digital cameras, medium format gear and 35mm film, Johnson followed butoh into landscapes that echoed its own darkness: mountains, hillsides, and the volcanic island of Oshima, where the cover image was taken. Improvised movement —central to his working method— dictated the rhythms. Johnson proposed groupings; Ishii Norihito —a dancer and choreographer with Sankai Juku, one of the most influential and celebrated butoh companies in the world— expanded them into almost spontaneous choreographies. Weather and atmosphere became part of the process. Chance was allowed to dance as well.

For Johnson, it was essential to show butoh’s less rigid face, closer to its underlying vitality. His photographs capture fugitive moments inside carefully constructed scenes: dancers eating lunch, riding a skateboard, checking their phones. In one image, several of them lick bright yellow lollipops under the sun, their painted skin gleaming. Johnson laments that “fewer and fewer young people feel called to butoh.” “It could disappear along with the generation that sustains it today.” He adds something that few notice: in this dance born from a wounded country, there is humour. A strange, almost spectral humour, but profoundly human

Why go so far just to arrive at a photography exhibition?

Because I want to draw attention to the superficiality of our experiences. The images that surround us, the artists themselves. Everything we perceive stretches its fibres back to the beginning of time. Each image has an unimaginable internal anatomy, and what we do —also because we cannot travel back in time with every blink— is structure its contemplation with little bones of our own. I do not doubt that dear Tom feels butoh deeply, but not as its creators did. For us, it is a brief flare we will forget within an hour. But butoh once spoke precisely of that: of the ephemeral nature of experience, of the fact that pain is the primary raw material of what we are, that nothing is simple and nothing is forever.

Butoh, by Tom Johnson, is published by Sixteen World; an accompanying exhibition is on view at 1014 Gallery, London, through November 28.

Comments powered by Talkyard.