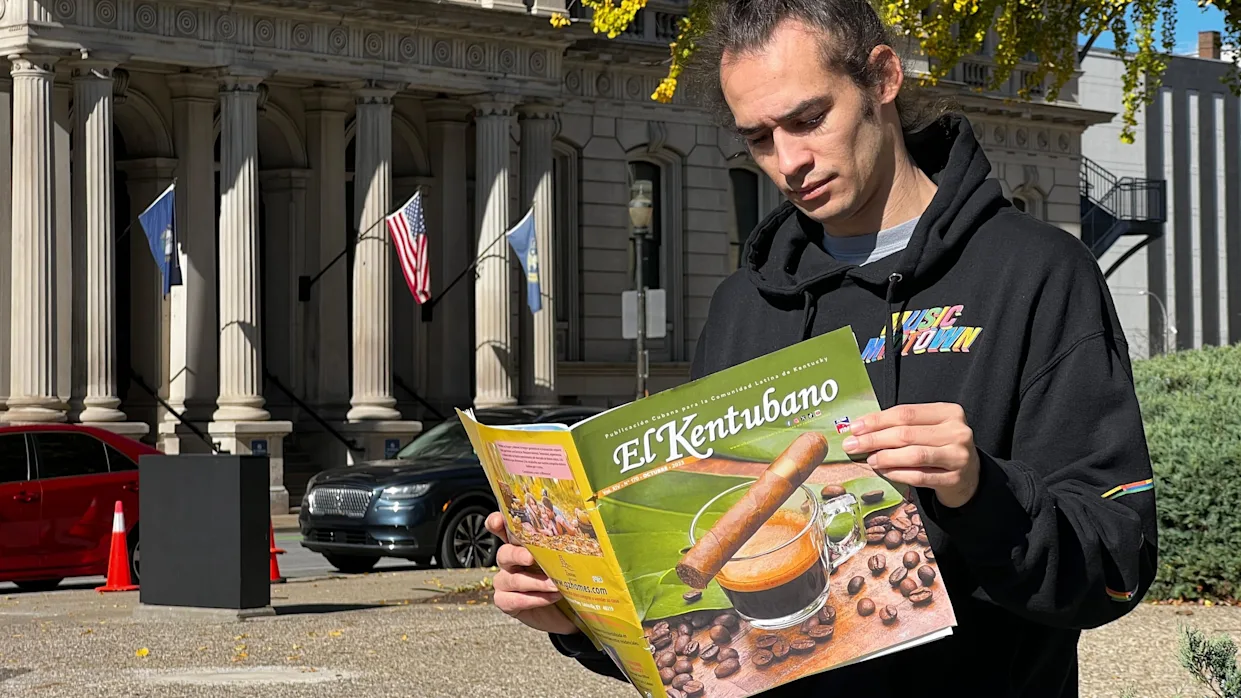

Local Faces: Jonny González, a passion for baseball and dreams that never surrender. #ElKentubano—exalting, recognizing, and applauding the good works and leaders of our community.

This past weekend, Annex Gallery carried out a working visit to Louisville, Kentucky, with the purpose of attending a talk offered by several Cuban artists on the challenging process of sustaining their creative practice within an economic, social, political, and even climatic context radically different from the one they had once known. The conversation took place at noon in the main hall of Louisville Visual Art and extended for nearly two hours. Four Cuban artists from the group engaged the local audience in dialogue about their experiences as emigrants while also delving into specific aspects of their work. The exhibition, titled Artistas Cubanos Chévere, will remain open to the public until August 21.

About these artists and about Cuban art in these latitudes we shall have time and occasion to speak later. Because—living the experience and considering the sheer number of Cubans who now live and work in Louisville—it occurred to me to conduct a small investigation into the origins of this community. To recount this story, first to myself, because I still struggle to believe it. I had heard vague rumors when I lived in Florida, but I could never have imagined the magnitude of this migratory phenomenon, which I would describe as extraordinary. Its magnitude, moreover, is relevant within the Cuban context, since Latin American migration in general has another scale and another nature.

Thus, Louisville, in the very heart of the Ohio Valley, known for horse derbies and bourbon, has become the stage of an alternative diaspora. What began as the nearly invisible presence of scattered pioneers in the first decades of the twentieth century has, over time, transformed into one of the most dynamic Cuban communities in the United States and the world. More than fifty thousand “Kentubanos”—as they call themselves—embody today a hybrid and singular identity, the outcome of a confluence between history, resilience, and a network of institutional supports that managed to discern the opportunities of migration.

At the beginning of the last century, the Cuban trace in Louisville barely registers in the federal censuses: isolated names which nonetheless already delineated a footprint. Engineers, laborers, modest entrepreneurs—men and women who found their place in a city just beginning to open itself to the industrial age. The professional diversity of those first settlers anticipated a feature that would repeat itself more than a century later: the innate capacity of Cubans to turn exile into an economic and social engine.

No less complex were the racial dynamics that traversed that early presence. The fact that some were recorded as white and others as Black reflects the plurality of an island transplanted onto a territory marked by the rigid segregation of Jim Crow. There were even those who attempted to reinvent their identity: Ferdinand Castleman Robinson, born in Kentucky, declared himself “Cuban” in the 1930 census, perhaps in search of social ambiguity, of exoticism, or simply because, by being considered foreign, he could rewrite himself within an implacable hierarchy.

Yet the great story was still to be written. After the 1959 revolution, hundreds of thousands of Cubans fled the island, giving rise to the celebrated Freedom Flights and to programs such as Operation Pedro Pan. Miami absorbed the majority of that torrent, while Louisville remained on the sidelines. But the creation of that vast demographic “reservoir” in Florida would prove decisive: it was from there, decades later, that many of those who would fuel Kentucky’s rise would come.

The true turning point arrived in 1995, when around eighty-five rafters from the Guantánamo camps were resettled in Louisville by agencies such as Kentucky Refugee Ministries and Catholic Charities. It was not a spontaneous migration but a deliberate institutional planting. That small group constituted the critical mass from which the community would grow organically and with accelerating speed.

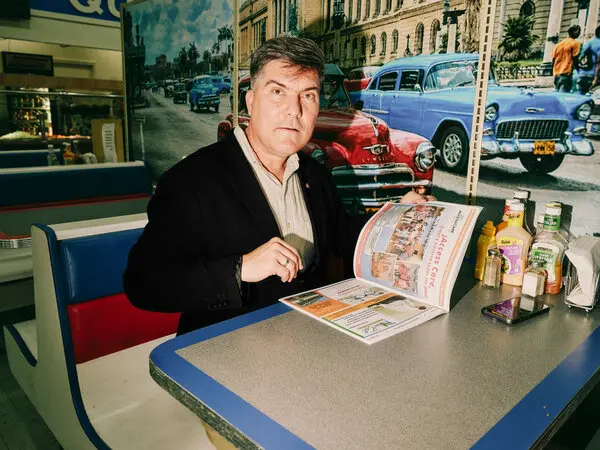

Luis Fuentes flips through the advertising pages of El Kentubano. Many Cuban businesses place ads in his magazine, which is aimed primarily at their community in Louisville. By Tracey Eaton | NBC News

From that seed sprouted a process of chain migration. Families arriving found fellow countrymen already settled, networks of support, and tangible proof that Louisville offered opportunity. Examples such as Berta Weyenberg, who in 1996 arrived with her children drawn by the presence of her brother, a physician, or Luis David Fuentes, who years later founded El Kentubano, illustrate the twin engines of growth: family reunification and economic ascent.

In the last decade, Louisville has ceased to be a secondary destination and has become a primary port of entry. The most recent catalyst was the opening of the Nicaraguan route in 2021, which multiplied arrivals. The figures are startling. More than nine thousand Cubans were resettled in the fiscal year 2024 alone, representing over three quarters of all refugees in the city. “The Havana of Ohio” is no longer a casual nickname but a demographic fact impossible to contest.

The attraction is comprehensible. In contrast to the prohibitive costs of Miami, Louisville offers abundant jobs in giants such as Amazon, GE, or UPS, competitive wages, lower taxes and rents, and—perhaps the greatest magnet—the real possibility of purchasing a home for less than $200,000. For those of us who grew up in a country where private property was a dream, owning a house means much more than stability: it is, in concrete terms, the realization of the American dream. To this must be added the existence of a robust institutional infrastructure: resettlement agencies that provide basic services, grassroots organizations such as La Casita Center, and, at the heart of the network, El Kentubano, the magazine that since 2009 has connected businesses, families, and aspirations. The ecosystem combines the official framework with the community’s lifeblood, creating a multiple support system that has enabled accelerated integration.

Kentubanos: the wave of Cubans transforming Kentucky’s largest city

The economic impact is visible: more than 500 Cuban-owned businesses now operate in Louisville, revitalizing neighborhoods, contributing taxes, generating employment. Iconic restaurants such as Havana Rumba or La Bodeguita de Mima offer not only native cuisine but complete cultural experiences. With the creation of real estate agencies, auto shops, daycare centers, and an endless array of small businesses, the “Kentubanos” have turned the city into a mosaic of enterprises where productivity and determination mingle with the intoxicating aroma of chicharrones and morning coffee.

As could not be otherwise, this dynamism has been accompanied by the cultural effervescence that any number greater than two Cubans naturally provokes. Festivals such as Sweet Havana Carnival in the city’s downtown, art exhibitions, and the proliferation of live music have made Cuban culture an ambassador that surpasses nostalgia and offers itself as a plural celebration. The “Kentubano” is no longer merely an inheritance from the island but an identity in its own right—hybrid, increasingly recognizable, and celebrated within Louisville’s social fabric.

Mojitos!

This growth also brings tensions, of course. The pressure on social services, the language barriers, and the risk that success may erode its own attractiveness all serve as reminders that every migratory epic will be marked by challenges. Yet the attentiveness and responsiveness of the Cuban community are already at work: associations and local leaders labor to accelerate work permits and ensure that the prosperity once fostered is distributed as equitably as possible. Louisville’s paradox is that, in order not to become a mirror of Miami—where Cuban identity often creaks under the frenetic metropolitan pressure—it must learn to manage with caution its own miracle and, above all, its expectations.

The century now behind us reveals the sediment of an unexpected journey: that of the nearly invisible pioneers of 1900 to the eighty-five rafters who in 1995 laid the foundation of a community; from that institutional planting to the cultural and economic flourishing that today shapes the city. Louisville is the new frontier of the Cuban diaspora, an example of how cities far from traditional routes can transform themselves into centers of identity, memory, and future. The “Kentubanos” not only found refuge: they reinvented a city and, in so doing, inscribed a new chapter in the extraordinary migratory history of the United States.

Cuban-American Association of Kentucky

Comments powered by Talkyard.