Léon Bénouville. La Colère d'Achille, 1847

While writing the previous chronicle, I took a few pauses to search for depictions of Achilles in the history of art. To my surprise, they are scarce—and rather anemic. The balance between his weight in the collective imagination and his trace in the visual arts is tenuous, almost absurd.

I stumble across La Colère d’Achille, a painting by Jean‑Achille Bénouville, completed in 1847. It now hangs in the Musée Fabre in Montpellier, France, specifically in the Salle Ingres et l’École des Beaux‑Arts. Bénouville—a French neoclassicist—devoted himself chiefly to historical, religious, and mythological themes. The trending topics of his time. The fashion of depicting the sordidness of local fauna would arrive many years later. His work is marked by rigorous composition, a restrained palette, and an idealized human figure—hallmarks of mid‑19th‑century French academicism.

This Achilles, ladies and gentlemen, is a poem. A pre‑furious poem. It is impossible to know the precise reason for this fit of pique—there were many. The Iliad unfolds in 24 cantos—24 “books” narrating just a few weeks in the tenth year of the siege of Troy. Decisive days in which our hero moved from one bout of rage to another. We must understand him: ten years at the foot of the walls—heat, cold, mosquitoes, serpents… without a bath. Hector mocking them from atop the ramparts.

If we are to swallow this piece like a bitter pill, in one gulp and without prior critique, we might say the image captures Achilles in a transitional state of restrained fury, laced with obsessive ideation. Such states are typical of someone deeply wronged or betrayed, yet still holding onto the barest thread of rational control. Tell us, Achilles, what is it that confounds you—Agamemnon, the death of your beloved Patroclus? Give us a hint. We might also say he stands in a moment of cognitive dissonance: he knows that an impulsive act could have grave consequences, but his body is primed for violence. This, I repeat, is what we might tell someone who has not seen the canvas.

And how does Achilles look in this work?

His eyes, wide as saucers, stare into nothingness. His posture reveals a surface tension in the muscles, far too light for a state of fury. His right hand rests against his temple. That clawed hand and that gesture strike me as contrived, a gratuitous artifice—a cheap device to signal his psychic tension. The way his feet are set—one ahead of the other—suggests that Bénouville cared more for the grace of the pose than for his emotional state.

Such would be the description of an art critic who happened to be the painter’s friend.

But in my view, within the iconographic tradition of the Homeric hero, it is bewildering—not to say laughable. The title of the painting promises a colossal fury, an eruption of divine energy, the very embodiment of the violence inherent in the greatest warrior of Greek myth. What I see instead is a muscular, dazed boy sitting in a chair as though awaiting his turn at the proctologist.

His nudity does not confirm the divine lineage of his attributes; it undermines them. His epic called for excess; what remains is restraint, and a rather shy one at that. His expression teeters on a pout. In his vacant gaze we do not see a hero in torment but a distracted man suddenly wondering if he locked the door, if he turned off the stove.

A lamentable misstep is the presence, off to the side, of a lyre. That symbol of balance between the Apollonian and the Dionysian is reduced to a decorative prop, almost a toy abandoned at the hero’s feet. What has a lyre to do with fury? Where is the spear, where the sword? The composition blends adolescent languor with a catalog‑ready neoclassical aesthetic.

Compared to the searing absence we encountered in the post about The Horses of Achilles—where the hero’s rage was embodied in the restless frenzy of his animals—this weakling is a footnote without verb or blood. What we glimpse is not fury but hesitation, glory turned to pose, mythology reduced to a stage set.

Bénouville does not portray wrath; he captures the inability to act, the collapse into empty introspection, a kind of premature, flavorless existentialism. The demigod, stripped of his most primal impulse, becomes a salon fop—fit, perhaps, to decorate the study of some solitary, melancholic aesthete utterly out of tune with the epic tale that begot him.

This Achilles is no hero; he is a symptom and a warning. A reminder of what happens when the lyre replaces the spear. A demigod without purpose or argument. An affront: a kingbird, a caged canary, a foolish dog, a stale biscuit.

Jacques-Louis, David. The Anger of Achilles. Google Art Project

P.S.

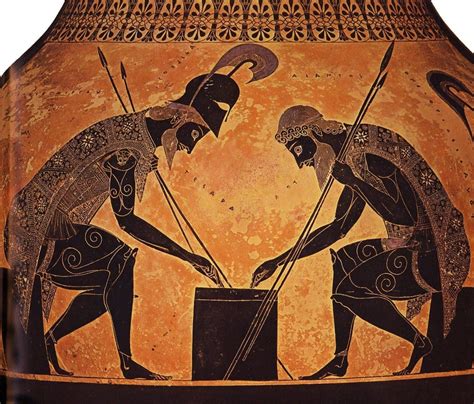

Other Achilles of similar ilk: Exekias’ amphora showing Achilles and Ajax playing dice, on view at the Vatican Museums. The Achilles who slays Penthesilea—also ceramic, by an unknown hand, nearly five centuries older than Christ—housed in the Staatliche Antikensammlungen in Munich. That cup shows Achilles killing the Amazon queen in battle, at the very instant their eyes meet and he falls in love with her. A full‑blown Greek tragedy. See in gallery.

Another of his rages: the one painted by Jacques‑Louis David, now in the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. Contradictory as well, because nearly everyone in the scene carries more presence and gravitas than Achilles himself. There are plenty scattered throughout art history.

Comments powered by Talkyard.