I ended the previous piece speaking about what has happened to my country after dismantling practically every vestige of its republican past. The revolutionaries abolished even the privately owned shoe-repair shops. They changed names as charming as “La Cenicienta” to Unit 256 for General Shoe Repair. They stripped them of every sign of identity, every trace of belonging. Where there had once been a prudent owner and two, three, or four cobblers, the space was taken over by a director and a deputy director...

I keep in my files an article The New York Times published on June 11, 2020. You’ll recall those were particularly unsettled months. The paper updated it on the 24th, while the protests over the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis—on May 25, 2020, at the hands of a white police officer—were still echoing. The crime—captured on video and broadcast everywhere—unleashed a global wave of outrage against systemic racism and police violence in the United States.

The greatest library of its age, that of Alexandria, burned intermittently over several centuries. Thousands of scrolls vanished, and with them much of antiquity’s science, philosophy, and literature. The intellectual inheritance of the ancient world was reduced to ash. We cannot rule out deliberate intent in some of those episodes. Long before, a vast portion of Phoenician-Punic art had disappeared in the wars we know as the Punic Wars. Nothing remained of Carthage, a cultural and artistic power of its time.

Not long ago I came across a Facebook post claiming that “sometimes… destroying art is art.” It offered three examples that, to my mind, have little to do with one another. Let’s take them one by one.

On the morning of November 15, 2022, two activists from Letzte Generation (Last Generation Austria) threw a black, oily liquid over Gustav Klimt’s Tod und Leben, on view at Vienna’s Leopold Museum...

The last time I was at the CAC was in late 2017, for Caledonia Curry’s exhibition—better known as Swoon—titled The Canyon: 1999–2017. It was her first museum retrospective. I don’t recall every detail with clarity, but I do retain the certainty that it was a profoundly inspiring experience. Eight years later I return to the CAC for the public opening of What a Revolutionary Must Know, by the Iranian American artist Sheida Soleimani (b. 1990, Indianapolis).

Perhaps it was possible, even then, to sense that Jesus of Western Avenue, inaugurated on October 16, 2021, at the Cleve Carney Museum of Art (College of DuPage, Glen Ellyn, Illinois), would become Tony Fitzpatrick’s final solo exhibition in his lifetime. The show gathered more than sixty recent works, reaffirming his—almost proverbial—fascination with Chicago’s urban nature and environment, expressed through his unmistakably personal graphic language.

A few weeks ago, a post appeared on my Facebook feed from the Beagle Freedom Project, celebrating the seventy-fifth anniversary of Snoopy — perhaps the most universal of all beagles. Since 2010, the Beagle Freedom Project (BFP) has been rescuing, rehabilitating, and rehoming animals once used in research laboratories. The initiative was born of people who, for some reason, paid special attention to this breed — probably for its docility and its good-natured temperament.

One of the people I love most in the world—among other reasons, for something like this—cried for several minutes upon realizing that the book which had occupied her for a brief stretch of time had come to an end. To close it and return it to the shelf meant abandoning a world she already considered her own: one where good and evil were distinguished in every conceivable way. Beyond its beauty, that universe offered purpose, a sanctioned form of contemplation, and a steadfast commitment to the benevolence of the spirit.

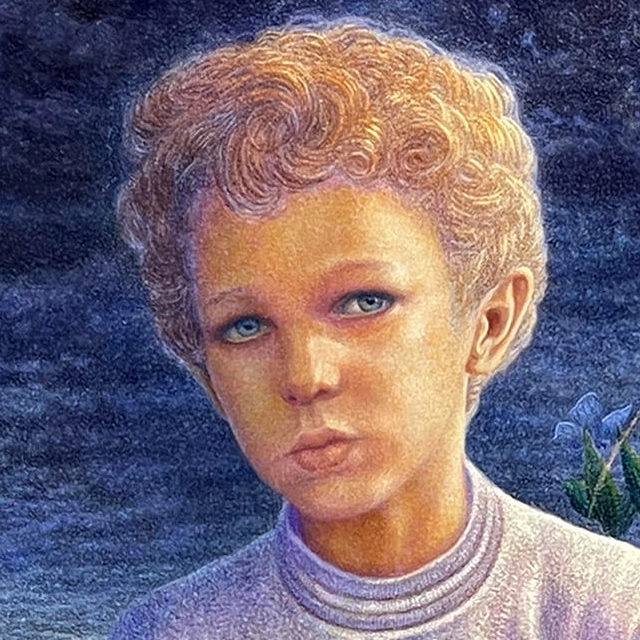

To speak of Kina Matahari is to confront the politics of disguise. Her work unfolds where visibility becomes dangerous and the body itself turns into a medium of camouflage. Between the myth of the colonial dancer and the lived reality of the contemporary artist, Skin as Camouflage traces a lineage of women who have negotiated power through performance, artifice, and survival. What begins as an act of concealment becomes, in her hands, a language of emancipation.