No confirmed remains of the Great Library of Alexandria have been identified, yet the city sheltered other marvels—above all its famed lighthouse—whose sheer monumentality left recoverable fragments. What does endure is a material ecosystem of learning and cult that sketches the intellectual landscape of the city: the Serapeum, often described as a “daughter library,” with the Column of Diocletian and portions of the complex, whose subterranean galleries are now read as ritual passageways rather than book stores; and the Kom el-Dikka ensemble, a cluster of late-antique lecture halls from the fourth to the seventh centuries that testifies to Alexandrian academic life without linking directly to the Great Library.

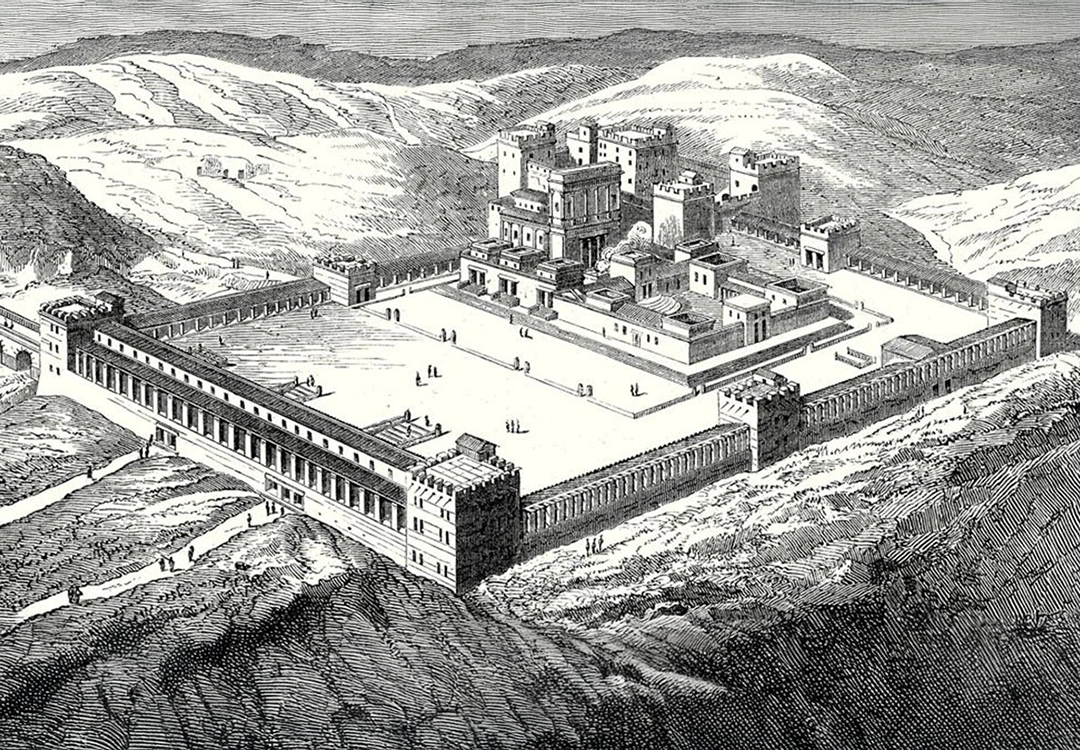

The greatest library of its age, that of Alexandria, burned intermittently over several centuries. Thousands of scrolls vanished, and with them much of antiquity’s science, philosophy, and literature. The intellectual inheritance of the ancient world was reduced to ash. We cannot rule out deliberate intent in some of those episodes. Long before, a vast portion of Phoenician-Punic art had disappeared in the wars we know as the Punic Wars. Nothing remained of Carthage, a cultural and artistic power of its time. Centuries later, the Roman legions of Titus would raze the Second Temple of Jerusalem in 70 CE, the spiritual and architectural heart of the Jewish people. The inventory of destruction does not end

That is what we were and, in many ways, what we remain. We are inscribed in the organic world’s logic, held in an unstable balance between life and death. One could even say we live merely to postpone the end of the cycle. Within that unfathomable chaos, fashioned for us by what cannot be scrutinized, art emerges as an act of symbolic ordering. It gives form to what has none yet and turns chaotic experience into representation that searches for meaning and harmony. Art functions as sublimation, channeling an instinct bent on restoring the human being’s equilibrium with its surroundings.

Artist's impression of the restored Second Temple which replaced Solomon's Temple, Jerusalem. From Les Merveilles de la Science, published 1870.

To destroy art is also natural, even organic. Entropy answers, everywhere and always, whatever resists chaos. Human beings carry disorder wherever they go. They take pleasure in unmaking forms, breaking symbols, fragmenting memory, plucking petals from daisies. This is the work of Thanatos, the drive that opposes an Eros stubbornly devoted to continuity.

Our response grows fragile where these cyclonic forces converge. A few exceptional individuals push beyond the minimum order that survival demands and produce something higher, what we call art. For me, it is the fullest expression of the will to endure.

There are also malign geniuses who elevate entropy, disorder, chaos, and the destructive vortex to an almost artistic pitch. As with art at the opposing pole, destruction can acquire a disquieting beauty.

From the beginning, humans have intuited that the power of the symbol resides in art understood as representation and unifying force. After the assailant tries to break the artist, the hand reaches for the work. It does so because the work is transcendent and because it keeps memory. A fragment of our species is there, crystallized in form, a kind of talisman promising the continuity of the self and of what one takes to be “one’s civilization.”

Let us turn to a few examples and see how popular cinema approaches this theme.

Begotten (1990), by E. Elias Merhige — an experimental, dialogue-free film that stages a cosmogonic myth in which the death of a deity gives rise to Mother Earth and the Son, who pass through a cycle of birth, destruction, and reconfiguration. Shot in harsh 16 mm black-and-white with deliberate degradation that scorches highlights and crushes shadows, it evokes ritual imagery and a timeless, archaic aura.

Begotten premiered in the United States in 1990. It is an experimental black-and-white film without dialogue. It stages the suicide of God as a cosmogonic myth. From the divine body the Earth Mother is born, and from her the Son, who moves through grotesque visions in a cycle of birth, death, and resurrection. Shot on 16 mm and subjected to extreme image degradation to simulate archaic or ritual footage, the film provoked equal parts rejection and fascination on release and has since attained cult status in experimental cinema. Violence, decay, and destruction become metaphors for creation and renewal. The figures move through a liminal space between annihilation and genesis, revealing the near-ritual dimension of imaginary destruction when it enables symbolic reconfiguration.

Fight Club (1999) — Brad Pitt and Edward Norton on the night when the club is born, along with the idea of “resetting” life.

In Fight Club (1999) there is a scene in which, after the Narrator (Edward Norton) and Tyler (Brad Pitt) brutalize Angel Face (Jared Leto), the Narrator confides in voice-over, “I felt like destroying something beautiful.” The line marks a fracture in his psyche. It is not only about the club’s physical violence. It names the destructive impulse as release, an urge to vent against beauty, perfection, and what has been placed beyond touch.

Donnie Darko (2001) — a mask, insomnia, and the intuition that destruction also creates.

Donnie Darko arrived in 2001 under the direction of Richard Kelly, a psychological science-fiction thriller whose gifted yet troubled protagonist begins to see a giant rabbit named Frank who warns him the world will end in twenty-eight days. What follows is a chain of events that entangles paranoia, time travel, and mental fragility. The phrase “destruction is a form of creation” recurs with insistence and suggests that breaking something can clear a passage toward a new reality. Destruction functions as symbolic reset.

Melancholia (2011) — intimacy at a human scale, cataclysm at a cosmic scale.

Lars von Trier’s canonical Melancholia (2011) imagines the end of the world with such meticulous beauty that destruction appears clothed in aesthetic grace. It operates as purge and as the consummation of the inevitable. Ruined heritage becomes emblem of a regime’s end or a melancholic transition. The cinematography amplifies the spectacle of collapse.

I could add five more examples and, if needed, another five. The undoing of whatever dares to endure is deeply lodged in the unconscious and leaps forth at the first opportunity. This is not about Ai Weiwei or about vandals who pour oil over classical works. It is about the wolf that governs a disquieting share of our subjectivity. It is Thanatos speaking from the dawn of human history. Even in so-called civilization the pattern holds. Some raise cathedrals. Others bring them down with demonic delight.

Art Under Threat

If art is also a form of equilibrium, it will always stand exposed to our compulsion toward imbalance. Creation demands the labor of integration. Destruction arrives at once and delivers a rush. Art embodies identity and thus becomes the victor’s first target. It also preserves memory and symbolic unity, which renders it vulnerable to any will that seeks to erase or rewrite the past. Statues of outmoded heroes—art nonetheless—were conceived to last and weigh accordingly, yet their fate is never secure. They stand in precarious balance under the constant threat of humanly generated chaos.

Is there any remedy for a humanity that creates and destroys symbols without rest? Perhaps the question does not close. Perhaps it simply opens the next bout between order and chaos.

Comments powered by Talkyard.