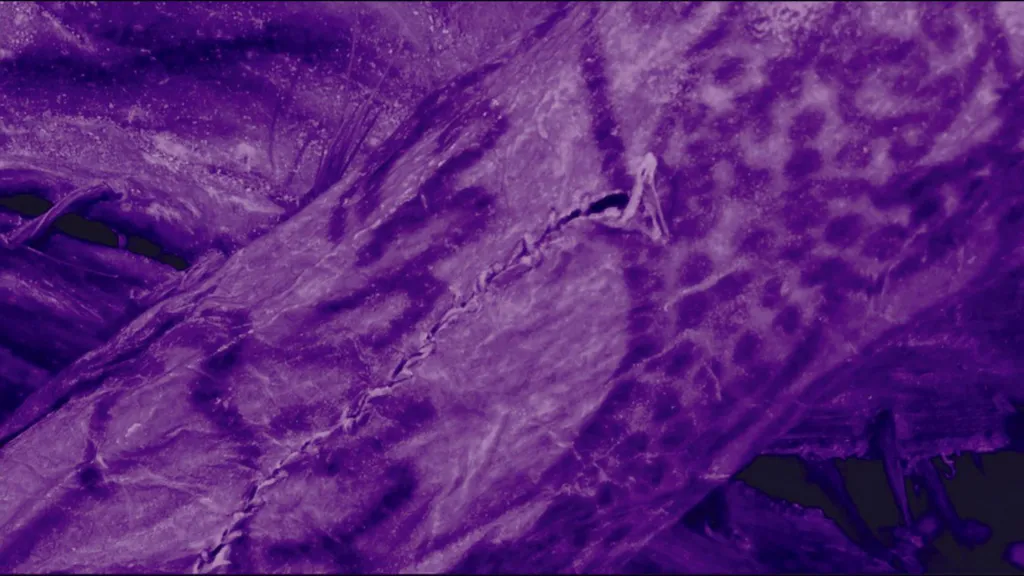

Scans of the ice mummy's skin revealed details of animals and birds on her arms and hand

God knows why I tend to read the BBC’s digital edition late at night. Perhaps because I enjoy — and at the same time, not entirely — its concise and direct style. It does, however, offer compelling articles on themes or events that larger media outlets often overlook. Georgina Rannard, for instance, published a captivating piece (in its English version) about the ancient practice of tattooing on the Siberian steppe. The illustrations caught my attention so intensely that I read the story first in Spanish, then in English — the latter usually offers more detail and photographs.

Rannard brings us to Saint Petersburg, specifically to the Hermitage Museum. Have you ever wondered about the name? It comes from the French ermitage, which in turn derives from the medieval Latin hermitagium, related to heremita or eremita — that is, a hermit. When Catherine the Great began collecting art, she stored it in a series of private chambers she called her ermitage — intimate, tranquil rooms to which very few people had access.

To the context

In the 19th century, in Russia’s Altai Krai, a series of burial mounds — kurgans — were discovered, belonging to a nomadic people who once roamed the southern Siberian steppe. They were part of the Scythian culture, active between the 6th and 3rd centuries BCE, known for their equestrian skill, their mastery of goldwork, their textile practices, and more recently, their remarkable tattooing techniques.

It was the Pazyryk Valley, in the mountains of Central Asia, that lent its name to a group of mummies found in exceptional condition, thanks to the permafrost. These tombs, excavated on high plateaus and valleys, became waterlogged by seasonal meltwater that seeped into their cracks. Over time, they froze completely, preserving the remains for millennia. As a result, not only bones but soft tissues — internal organs, hair, nails, and skin — were preserved. Today, we can examine not only their skeletons but also their garments, hairstyles, and most remarkably, their tattoos.

The most famous of these finds took place in 1949, when archaeologists uncovered a monumental tomb containing the body of a man — presumably a tribal chief or elite figure — surrounded by funerary offerings: horses, finely crafted ornaments, and textiles of great value. Later, in 1993, archaeologist Natalia Polosmak discovered the body of a woman — now housed in the National Museum of the Republic of Altai — buried alone, in ceremonial dress and unarmed, with tattoos on her left shoulder and arm. One of them depicts a deer with antlers in full bloom.

So far, evidence suggests that tattooing was apparently reserved for individuals of high status and was relatively common among women of elite rank. One such woman — dated to around 500 BCE and conserved at the Hermitage Museum — was recently scanned using high-resolution infrared imaging, revealing tattoos that had remained invisible to the naked eye.

Unlike in other cultures, where the body is often viewed merely as a disposable vessel for the soul, the Altai nomads seem to have regarded it — much like we do in the 21st century — as a narrative surface on which to inscribe symbols and histories. Their designs likely served symbolic functions, possibly tied to status, spiritual protection, or genealogical storytelling. These were not gratuitous decorations: they were language, identity, and shield against the threats of existence.

Here, the astonishment

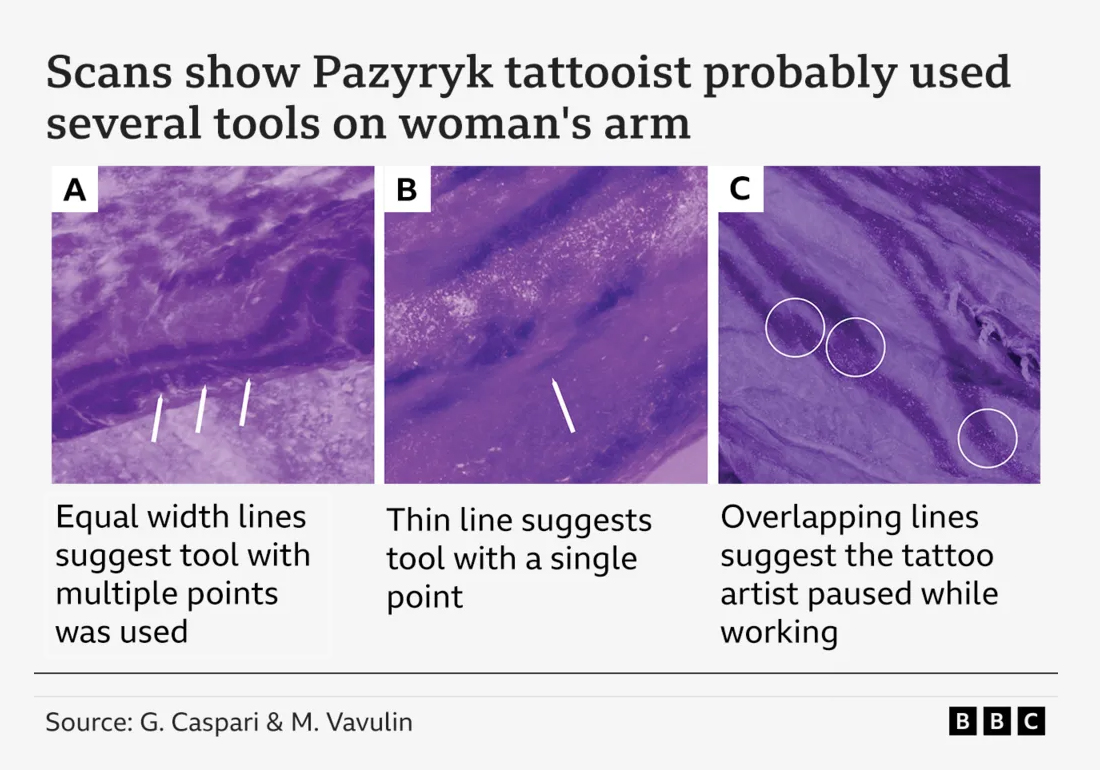

Not only for the BBC — but for me as well — the astonishing element lies in the complexity of these designs, considering their antiquity. These motifs are so intricate they would likely make any seasoned tattoo artist break into a cold sweat. The precision and consistency of the lines astonished everyone. These tattoos were complex, precise, and strikingly uniform. For Gino Caspari — archaeologist at the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology and professor at the University of Bern — the images were far from mere records: they made him feel dangerously close to those ancient artisans, as though he could sense, in each arrested stroke, the rhythm of their learning and the meticulous consciousness of their craft.

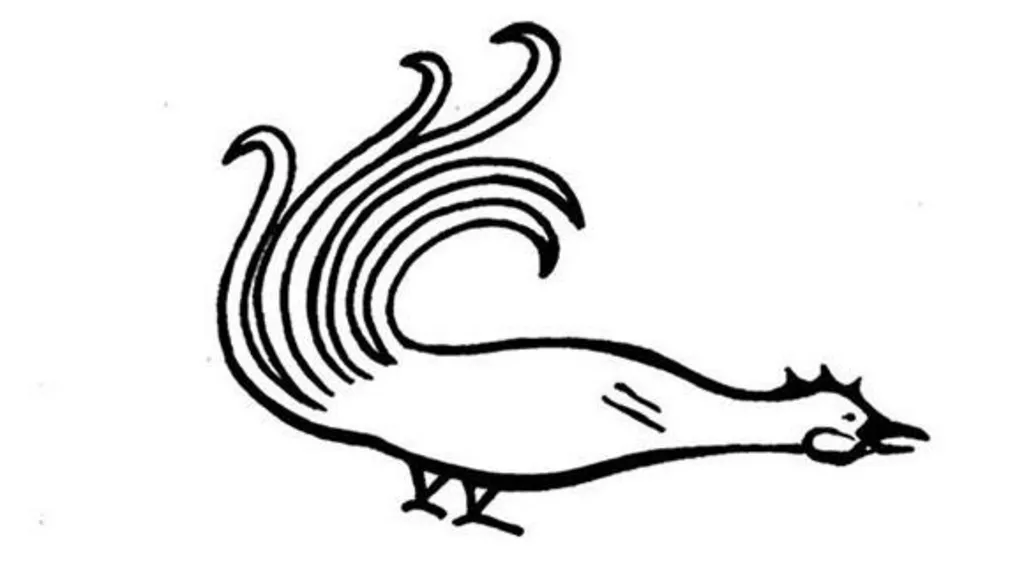

With the force of a bestiary, the woman’s right forearm displayed leopards circling the head of a deer. On her left, a griffin — a creature with the body of a lion and the wings of an eagle — was shown mid-combat with another horned beast. The oblique arrangement of the bodies and the dramatic intensity of these scenes were not ornamental: they formed a distinct aesthetic signature of Pazyryk culture. Yet there were also unexpected elements. A rooster tattooed on the thumb revealed a stylistic divergence. The contrast between the violence of the figures and the precision of their lines suggests that these tattoos did not follow a single shared visual code, but rather may have held personal meanings, narrative fragments, or emblems of identity.

Allow me to go slightly beyond what the BBC has said and offer an interpretation of my own.

Let’s dwell on the complexity of the drawing and its level of synthesis. It doesn’t use linear perspective or a single vanishing point. It’s a flat, two-dimensional composition, where the bodies are arranged symbolically and narratively, not naturalistically. Even so, it achieves a powerful illusion of movement using only curves, overlapping, and directionality. The bodies are distributed in a centrifugal composition that spirals around the deer’s head, which serves as the visual anchor. There’s no conventional spatial depth, but there is a rhythmic, circular perception — something akin to tribal emblems.

An illustration of the tattoo on the woman's right forearm revealed in new scans

The execution relies on precise contour lines of varying thickness — intentional and valued — that define the figures clearly, with no need for shading. Such control speaks not only to technical skill but to a sophisticated understanding of visual balance. The animals are not depicted realistically. The tiger, the leopard, and the deer have been rendered in stylized forms, refined to the edge of graphic design. Their graphic patterns (spots, stripes, antlers) identify them more by symbolic or heraldic value than by anatomical study: expression of gesture is prioritized over anatomical fidelity.

An illustration of the tattoo on the woman's left forearm revealed in new scans

One of the most striking features of these tattoos is their ability to transmit energy and tension. The posture of the felines, their arched backs, sublimate the brutal intensity of the hunt. The curve of their spines enhances their violent aggression, while the deer’s posture — neck twisted backward — invokes collapsed beauty, fragile and exposed. The interplay of bodies was conceived, unmistakably, with choreographic awareness — like a scene in perpetual rotation. The effect is hypnotic, and at the same time, dramatic.

Though the image uses very few visual resources — just black lines on pale skin — the result is sophisticated. The repetition of related forms (curves, claws, antlers) acts as a visual rhythm that guides the eye. This economy of means suggests a distilled technique, likely carried out with tools requiring extreme precision and control. The use of line alone — without shading or tonal gradients — demands extraordinary manual skill to achieve uniformity, symmetry, and fluidity.

An illustration of the tattoo on the woman's thumb and fingers

Beyond its refined graphic execution and aesthetic complexity, this ability to condense energy, mythology, and beauty onto a living surface like skin speaks of a practice that was not marginal, but deeply ritualized and professionalized.

Even if it’s not my primary concern, one cannot help but wonder how they did it.

Archaeologists turned to researcher Daniel Riday, who recreates ancient designs on his own body using historical methods. Based on analysis, Riday believes the tattoos were first stenciled onto the skin and then pierced using multi-pronged instruments made of bone or horn. The pigment was likely derived from soot or charred plants. The process was neither brief nor superficial: estimates suggest the woman’s right arm alone could have required nine to ten hours of work.

What interests me far more — infinitely more, I’d say — is what these tattoos reveal about life and death in those times. Some of them appear to have been cut or damaged during the preparation of the body for burial, suggesting that their value lay primarily in the world of the living. They may have held meaning or function during life, but not necessarily for the afterlife.

A curious parallel with 21st-century tattooing. The distinction between the social body and the funerary body opens new questions about the symbolic function of skin as a narrative surface in ancient cultures. But for a civilization that left behind no written texts, the skin was perhaps their canvas — the place where a mark could be left in the archaeological memory. As indelible as it was on their own flesh.

Comments powered by Talkyard.