Frida Kahlo in what is now the Casa Kahlo Museum, circa 1947. Credit: Museo Casa Kahlo.

It is enough to walk long enough through the arteries of any major city for the iconic eyebrows of Frida Kahlo to emerge from some unexpected corner. Alongside the Virgin of Guadalupe and the poblano chili, they constitute Mexico’s leading exports and a confused symbol for millions of women worldwide. In her homeland her image circulates on banknotes, perfumes, and the most unimaginable supports. To give you an idea, I once found her on the shelf of a grimy pastry shop in Baku, Azerbaijan.

My relationship with Frida has had its ups and downs. I visited the Casa Azul a long time ago—a small, fascinating museum whose spaces, intimate and reverberant, have kicked death itself out the door. Frida remains so alive there it feels as if she has just stepped out to buy bread. Years later, I indulged—almost morbidly—in the film starring another illustrious Mexican, Salma Hayek, in 2002, directed by Julie Taymor. Artist, actress, and director delivered an inspiring work that contributed to Frida’s enthronement as a universal symbol. Yet beyond these emotions, with a cooler head, the thought struck me that too often Frida’s story had been consumed without seasoning, stripped of its necessary condiments. Resilience, plain and bare. The film’s soundtrack lent her a vibrant—yes, I dislike the adjective, but here it is necessary—and deeply human dimension, counterposed to the mestiza goddess effigy that admits only tributes of color.

It is also curious to see how the once iconic Diego has slowly dissolved in the unexpected pardon Frida granted him in life, a pardon most of us have since withdrawn.

But the total Frida conceals, in my almost humble opinion, a great deal of poetic substance that may be revealed in what is now exhibited in the Casa Roja.

The Kahlo family held birthday celebrations and gatherings in the Red House until only a few years ago.

Fully aware that Frida’s contemporary image demands to be reformulated with a feast of minor details, the city has opened, three blocks from the Casa Azul, a Casa Roja. Opened to popular curiosity, it lays bare the artist’s intimate territory in the form of a domestic archive. If the Casa Azul has triumphed as a telenovela across half the globe, the Red one is a prequel. It narrates the origins and the affective network that made a Frida Kahlo possible, shifting the focus from export icon to the context that engendered her. A profusion of small details now joins those long visible in the original museum.

The house belonged to Cristina Kahlo, Frida’s younger sister, who moved there some time after her affair with Diego Rivera.

Cristina, the youngest of the Kahlo sisters, owned that Casa Roja. After marrying Frida, Diego Rivera paid off the mortgage on the Casa Azul. Yet this gesture—perhaps too intrusive—was not well received. Guillermo Kahlo, Frida’s father, came to feel that house was no longer his, and the family’s intimacy reorganized itself, taking shape within Cristina’s home. There they celebrated birthdays, settled conflicts, and accompanied Frida in her hardest moments, both physical and mental. There too death surprised Matilde Calderón, the mother, in 1932. From then on, this house sustained the affective fabric of the Kahlo clan. Meanwhile, the Casa Azul grew tied to the public and political sphere. León Trotsky and his wife, for instance, lived there between 1937 and 1939.

Portraits of the Kahlo family still hang in what was once the dining room.

The intimate stories of this new setting will rearrange many details of the biographies. After the ill-fated episode with Diego Rivera, Cristina resurfaces as her sister’s chief ally. She accompanied her through the painful convalescences of surgeries and procedures, weaving the practical and emotional fabric that souvenirs are still incapable of conveying. The Casa Roja also sheltered Frida’s encounters with Trotsky and with Isamu Noguchi, who on one occasion, upon hearing from the servants that Diego Rivera was approaching, scrambled up a lemon tree in the courtyard and fled in panic across the rooftops.

What the newly opened Casa Roja exhibits is not the Frida of catalogues. It is the relics of her domestic life: letters signed with diminutives, photographs, dresses, dolls, medicines, gas receipts. It even honors the memory of Guillermo Kahlo with a red, darkened room that recalls the migrant father and photographer who sharpened his daughter’s gaze.

Room dedicated to Guillermo Kahlo.

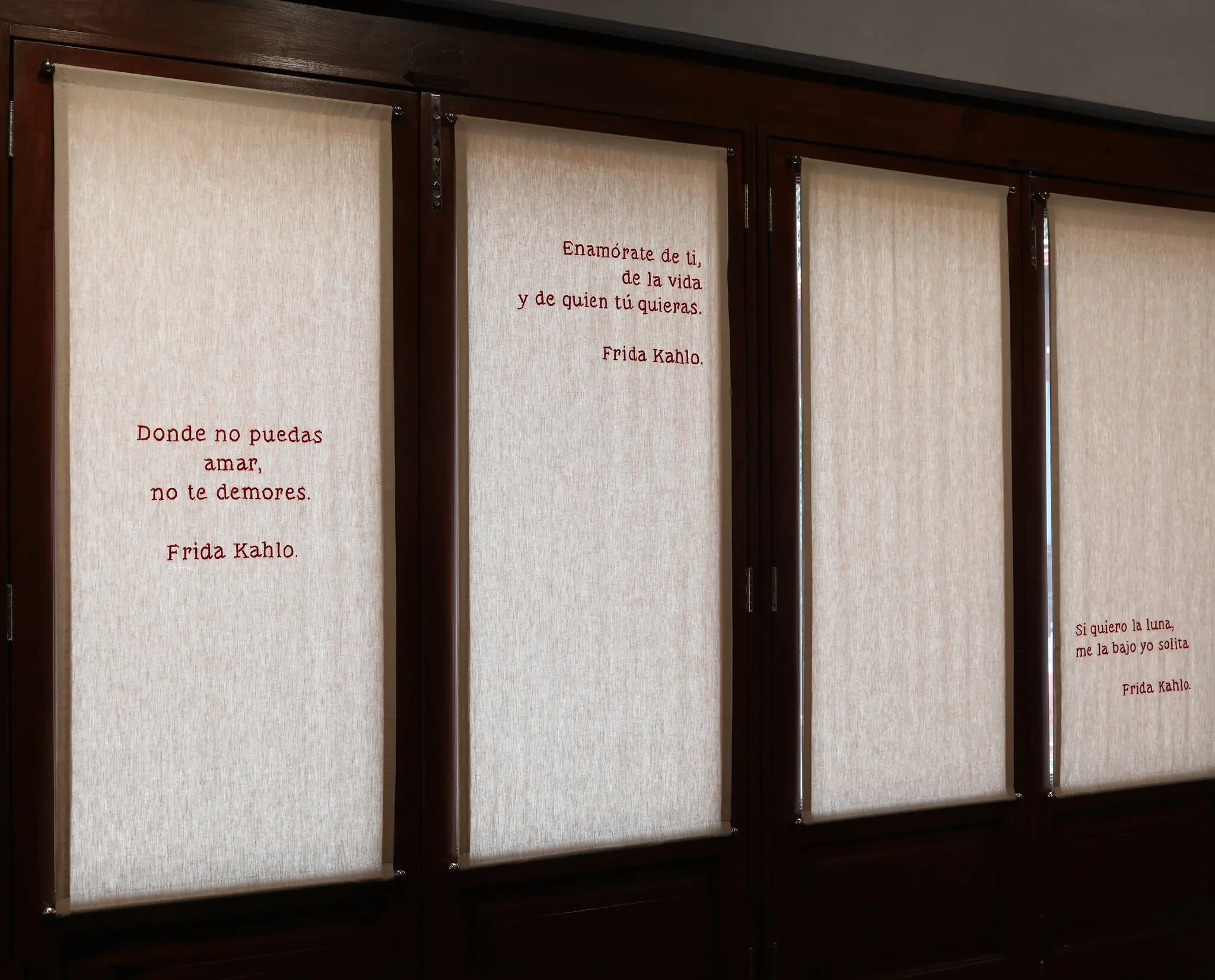

The museography, designed with David Rockwell Studio, avoids digital spectacle. Rather than aestheticizing her daily life, it documents it. And it does so through an analog, fully sensorial reading. Windows are veiled with embroideries made by women who today invoke Frida as homage—“What would I do without the absurd and the fleeting?”—returning to her work the domestic cadence that nourished it. The curatorial gesture is completed with El mesón de los gorriones, a possible mural by Frida in the kitchen (c. 1938), where the play on “gorrones” [spongers] ironizes about the diners and the sharing of the common. The grapefruit tree planted in the patio and the tree in the mural intertwine olfactory and visual memory, binding the living house to its representation.

One might say that this new Casa Roja reframes the gaze the Azul has been shaping for far too many years. And it fulfills a definition that until now had been merely theoretical: the sisters’ affective scaffolding, the whispers at the table, the modest traces of their small economies. The Azul confirms itself as public mythology; the Roja exposes the bones that uphold the symbology.

With the support of the Kahlo Foundation, the project adds a prize and grants for emerging artists, yet its greater contribution is to displace Frida from mercantile icon to domestic archive, to restore context, human scale, and above all, to render visible the fabric that made a work of such magnitude possible.

Comments powered by Talkyard.