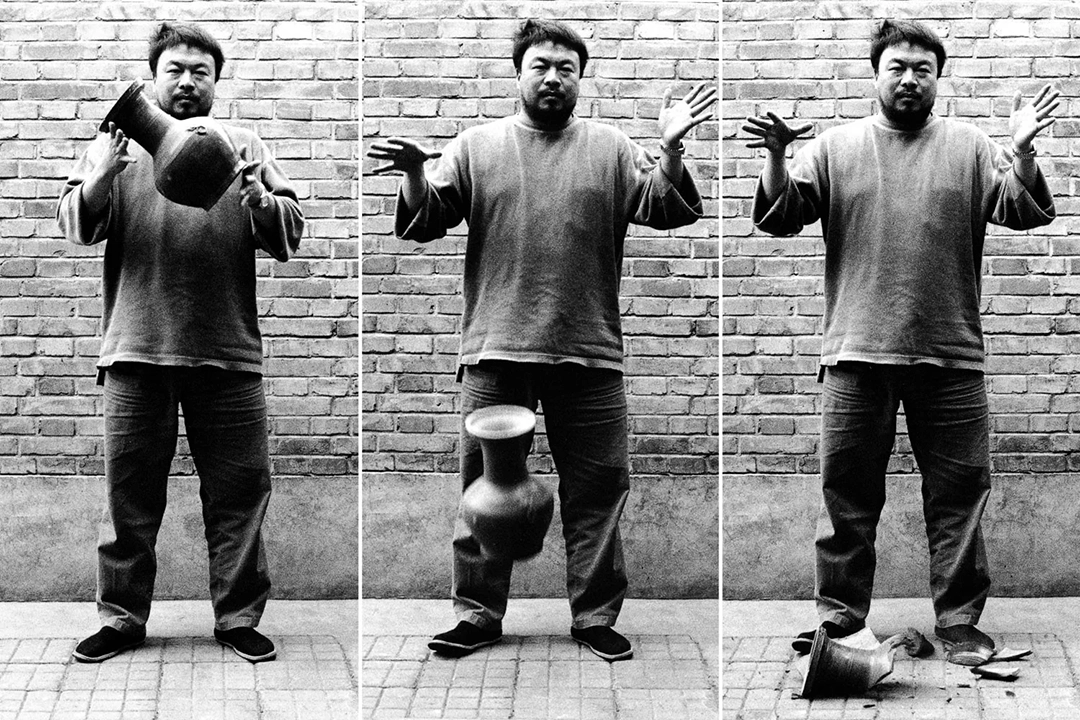

Gustav Klimt, Death and Life (1910–1915), Leopold Museum, Vienna. In November 2022, climate activists from the group “Last Generation” splashed black liquid onto the painting to protest the climate crisis. The work—which sets the figure of Death against a cluster symbolizing Life—sustained no permanent damage, thanks to protective glazing.

Not long ago I came across a Facebook post claiming that “sometimes… destroying art is art.” It offered three examples that, to my mind, have little to do with one another. Let’s take them one by one.

On the morning of November 15, 2022, two activists from Letzte Generation (Last Generation Austria) threw a black, oily liquid over Gustav Klimt’s Tod und Leben, on view at Vienna’s Leopold Museum. Klimt began the piece in 1910 and reworked it many times over the following six years. It is likely he had doubts, for the theme bears such depth—such symbolic weight—that with the slightest misstep it tilts into the puerile. Of Klimt’s works—though it is a key piece of Austrian modernism—it is among those I like least.

The attack protested Austria’s fossil-fuel industry—particularly the company OMV, which happened to be sponsoring the museum that very day for St. Leopold’s Day. There was no permanent damage. It cannot be called iconoclasm, since the intent was to stage a political performance. I have also read that such incidents should force museums to rethink their role amid social and environmental crises, insofar as a work of art today can shift from an object of contemplation to a vehicle for symbolic mobilization. What colossal nonsense.

Banksy’s “destroyed” painting sells for over €21 million.

This marks a record for the Bristol-born artist; until then, his costliest work had been Game Changer, a drawing he donated during the pandemic, with proceeds directed to the UK’s National Health Service.

The second example is the live destruction of Girl with Balloon

On October 5, 2018, Sotheby’s held an auction in London. Among the lots was Girl with Balloon, made by Banksy in 2002—one of his most iconic images—a screen print on canvas, framed. As the hammer fell at £1,042,000, a hidden mechanism in the frame was triggered. The canvas slid down and a shredder concealed within the frame sliced its lower half into strips.

Banksy had installed the mechanism years earlier, intending the work to “self-destruct” if it ever went to auction: a personal action against the commodification of art, a deliberate gesture that turns destruction into creation. In fact, what remained of the original—and I still suspect this, too, was deliberate—led the artist to rename the piece Love is in the Bin (2018). Here the destruction came not from outside but from the author himself, producing a new work that multiplied in value. There is much to unpack. But in the end, Banksy “destroyed” a piece that, in some sense, was and remained his.

Sotheby’s sold it again for £18.6 million in October 2021, unlocking an unexpected level of fetishization. The case sharpened a debate in contemporary art: can deliberate destruction also be a creative, critical act?

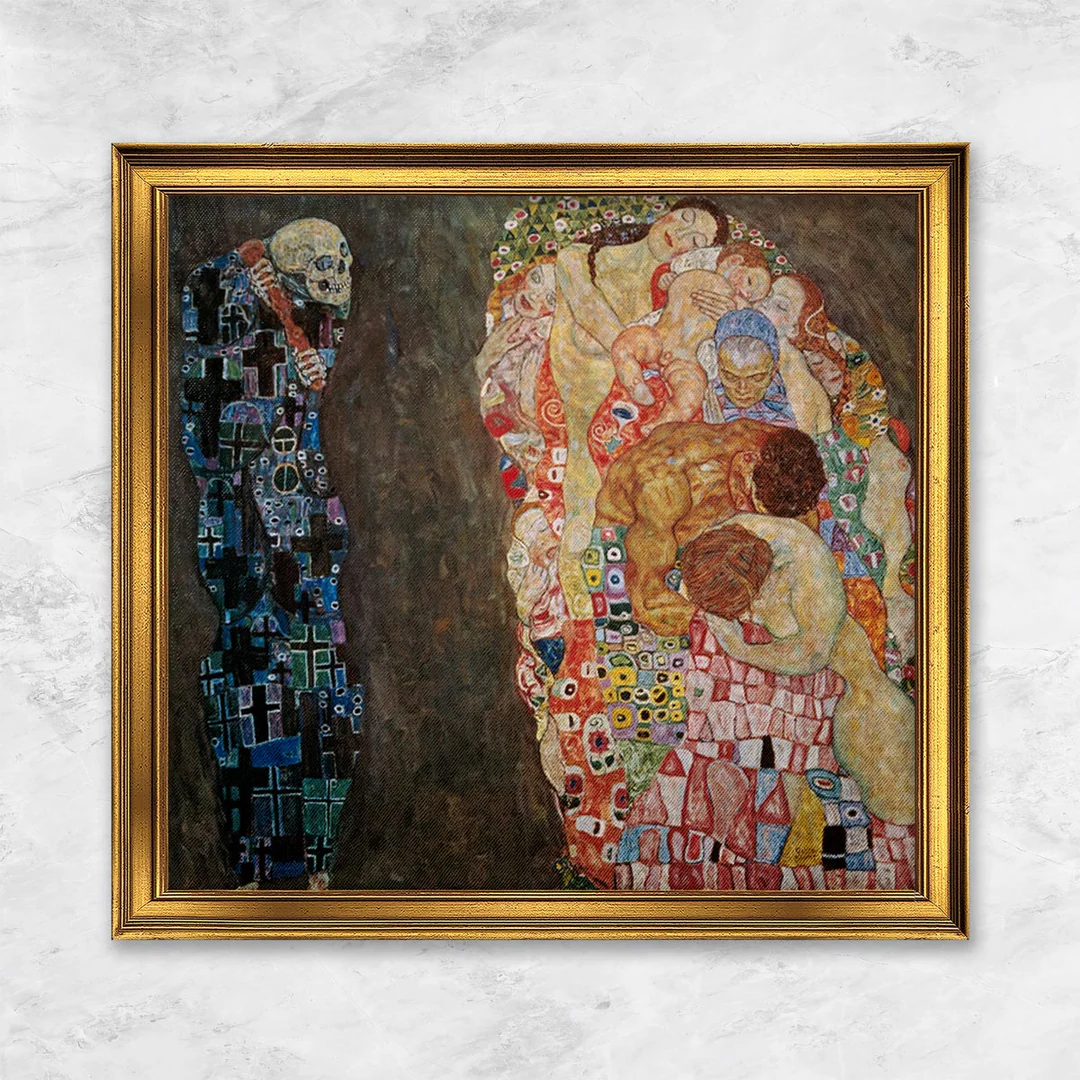

Although the work’s label indicates the vase was from the Han dynasty—as the artist himself has stated—the absence of comprehensive public documentation regarding its provenance and authentication leaves its status as an “irreplaceable” heritage object partially indeterminate. This, however, does not diminish the significance of the artistic gesture; it merely frames it within a strategy that questions, precisely, the very notions of authenticity, value, and patrimony.

The third case

In 1995 the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei drops a Han-dynasty vase (roughly two thousand years old). The action is recorded in three moments: he holds the piece; he releases it; he watches it shatter on the floor.

In my view, Ai Weiwei perpetrates an artistic action—because that was his intention—but also a criminal one, with malice aforethought and cruelty. It is carefully premeditated. He ensured there was a camera to document it and make it public. He aims to convert his act of destruction into cultural myth, fixing for eternity his image as absolute transgressor.

Ai Weiwei challenges the sacralization of heritage, treated as untouchable by any critical intervention. He also denounces the Chinese state’s power to decide which objects are sacralized as “national treasures.” By destroying a millennia-old object of such high economic and symbolic value, he exposes the tension between material value and conceptual value—and may well seek to alter the prevailing value system. Put simply: to persuade the system that the vase he smashed is worth less than the performance and the documentation that replace it.

From the other shore, since one cannot trade blithely in scarce two-thousand-year-old vases, it is an excellent marketing idea to sell the crime—with all its political charge, needless to say—in as many editions as possible, at an even higher price. Two artist’s proofs and an edition of ten, for instance.

The industry has treated the gesture as an action against history that produces a new critical object—one that confronts how both the communist regime and the art market instrumentalize the past. And it offers yet another bit of nonsense: to reconsider the weight of tradition under the urgencies of the present.

Do not mistake me. There is nothing more alluring than attending to the present. But just as we do not tear up our childhood photographs—when we were vulnerable and foolish—we do not need to destroy two-thousand-year-old vases to propose or assert a new civil, economic, or historical order, or whatever one wishes.

I have divided these reflections into several parts. In the next, I want to address the unnerving pleasure—the almost narcotic vertigo—induced by any act of destruction: the savor of that brutal, intoxicating, euphoric surge of dopamine that makes us feel like true animals.

Comments powered by Talkyard.