Go to English Version

Go to English VersionLeafing —digitally— through the latest issue of Tech Life magazine, I come across this advertisement for Luminar 4. I was almost seduced—abducted, rather—by the promise of a digitally retouched future.

A brief investigation confirms that Luminar is a photo-editing software developed by Skylum. It is built upon artificial intelligence and stirs considerable curiosity in the market of credulous souls, among the devotees of technological tinsel and those with very little resistance to the allure of advertising. It incorporates automated tools such as sky replacement (AI Sky Replacement), texture enhancement (AI Structure), and portrait and skin adjustments (AI Portrait and Skin Enhancer), capable of transforming images quickly and with seeming realism. Its interface is organized by tabs to facilitate a simple, non-destructive workflow. It includes pre-designed styles (“Looks”) applicable with a single click, whether in its standalone version or as a plugin for Photoshop or Lightroom. Although its library management is limited and some processes can be slow, it stands out for its accessibility, the strength of its algorithms, and the possibility of achieving professional results without the need for a steep learning curve, which makes it an appealing alternative to traditional editors like Lightroom, especially for those who seek efficiency and creativity through a single payment without subscription.

As you can see, it is easy to be carried away by what digital marketing specialists so skillfully tell us.

Advertisement for Luminar 4, in the Tech Life magazine published yesterday, August 16, 2025

In advertising, the ability to dazzle is the ultimate weapon: a touch of artificial brilliance is enough to leave the audience wide-eyed. The usual strategy is to saturate the product at hand with colors, promises, and flawless smiles so that no one dares to inquire about the essential. The average consumer does not seek depth, but sparkles; not certainties, but the lightning flash that distracts him for a fleeting second from his tedium. And thus the marketplace becomes a grand spectacle of fireworks where the real value of the product matters little: what counts is to dazzle just long enough to warm the credit card before the eyes adjust to the dreary penumbra of reality.

My alarm went off at the thought of an application like this being used on the passersby of our images—on the niece who will become, in turn, an aunt, a grandmother, an ancestor smiling from an HD photograph. Will we attempt to advance toward unreality, merely to dazzle the descendants who are not yet born?

Family memories altered artificially are no longer memory at all, but packaged mirages: a sugar-coated postcard where wrinkles are erased, silences are filled with smiles, and even the most unbearable uncle is transfigured into a saint. What purpose would there be in storing such falsifications? What value could they hold in the hidden marketplace of our memories? The same as a piece of imitation jewelry that shines, moves, even impresses the foolish, but that at the first severe glance betrays its poverty. With each Luminar retouch, what might have been testimony is reduced to caricature, what once was heritage is degraded into domestic family propaganda. In the end, the only authentic trace that remains is the evidence of our desperation to embalm time, to graft false perceptions into the minds of people we will never know.

The corruption of memory is abominable. One thing is the historical discourse of the dominant caste—the victors—accepted as truth under penalty of being cast out from the massive chorus of popular adulation, and quite another is to deceive the grandchildren of our grandchildren. I, who believe in the ascension of the soul, would be deeply ashamed to arrive in heaven and have my great-great-grandchild ask me: “And who are you?”.

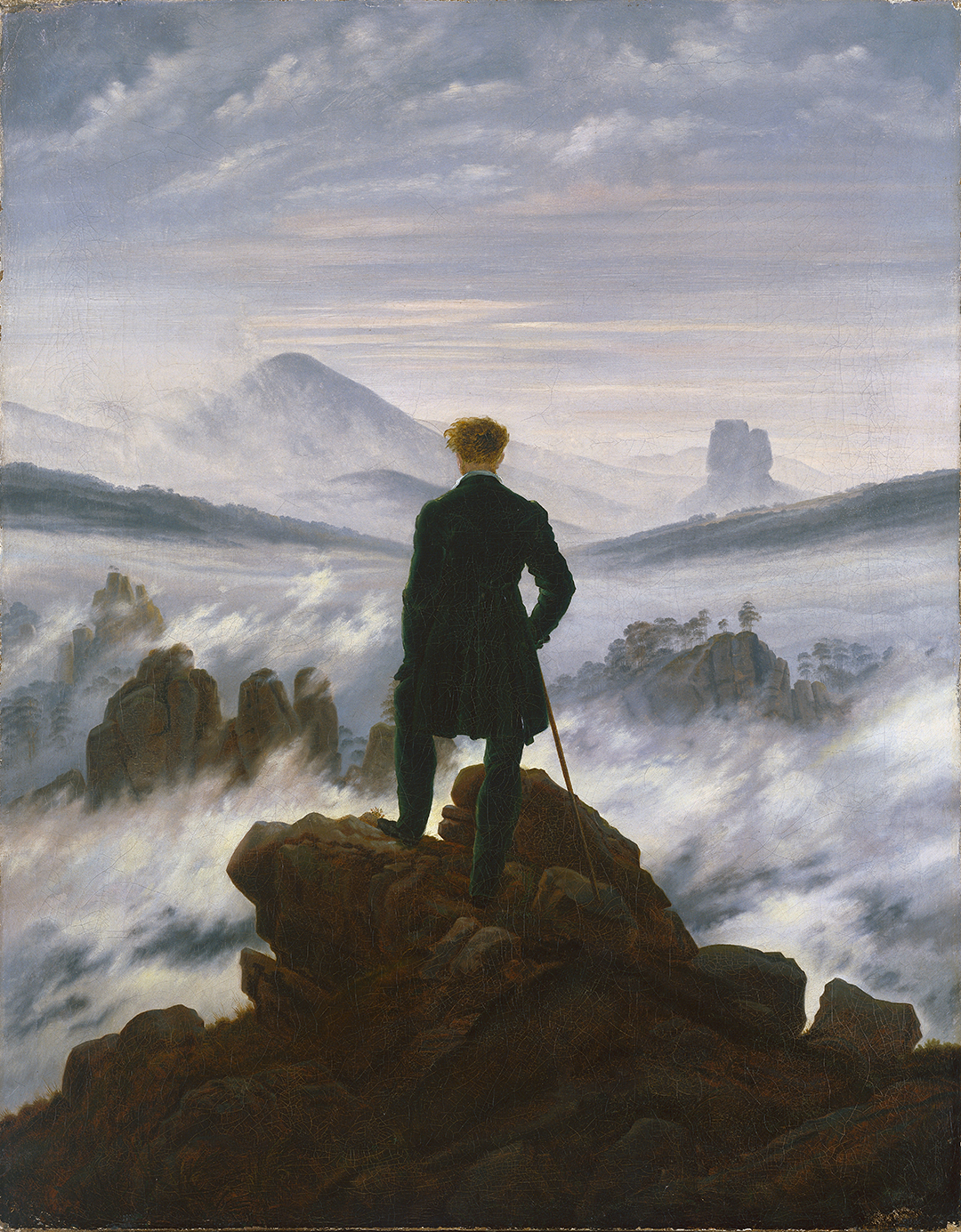

Caspar David Friedrich. Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, 1818. C. D. Friedrich was a German Romantic landscape painter, generally considered the most important German artist of his generation, whose often symbolic, and anti-classical work, conveys a subjective, emotional response to the natural world.

Postscript

Caspar David Friedrich. Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, 1818. C. D. Friedrich was a German Romantic landscape painter, generally considered the most important German artist of his generation, whose often symbolic and anti-classical work conveys a subjective, emotional response to the natural world.

In 1818, Caspar David Friedrich painted The Wanderer above the Sea of Fog: a solitary figure seen from behind, who—without any retouching—embodies the smallness of the individual before the sublime. It was a profound, almost mystical reflection on the relationship between humankind and the immensity of nature.

Two centuries later, a graphic designer—perhaps—chooses to place a little figure in a red jacket, perfectly centered, on the rim of a turquoise crater. The composition is identical, yet the purpose is no longer to stir the Romantic soul, but rather to supplant the work of God and magnify the immensity of the witness. The appearance of a prefabricated aesthetic gravity. The original invited contemplation and existential vertigo; this digitized version seeks instead rapid consumption, the prepackaged depth that will most likely be ignored amid the superficial intoxication of emotional merchandising. Friedrich contemplated eternity; this one, God knows, contemplates the screen, the number of likes. And who, in the end, really cares?

Comments powered by Talkyard.