There are not many mammals—imposing ones, at least—among the Nazca geoglyphs. No lions, no horses, which arrived in the Americas with the Spaniards in the sixteenth century, long after the lines were drawn (approximately 200 BCE–700 CE). There are dogs and cats, monkeys, serpents, parrots, whales, and the famous hummingbird, to me the most beautiful of them all.

Many of us love stories about extraterrestrials. Enjoyable, measured, tinged with mystery. For some, though, they become a feverish fixation. They comb the internet the way people once prowled libraries, hunting for hidden messages, for the codes and arcana exchanged in some shadowy dimension—guardians of the secrets.

They see in the Nazca figures one of these “proofs.” According to their logic, if back then no one could reach the altitude needed to behold them, the figures must have been made for those who could—or, far more thrillingly, for those who descended. The knowledge of the time was more than enough to understand that the majestic Andean condor could see them. Their gods, on the other hand—who were not gods in the Greco-Roman sense but hybrid supernatural beings common in the pre-Hispanic Andean imagination—had something human in them, but far more animal. Because humans, somewhat defenseless, realized that nearly all animals possessed abilities that overwhelmingly surpassed theirs. Any little fish could survive longer underwater than the one they named “the man of immense lungs.” And what to say of birds, those who crossed the sky, gods of omens, who connected the human world with the divine: the “messengers,” of course.

What is undeniable is that they outlined the figures, and there they remain for anyone who can afford the ticket. And yes, they were made with a purpose. Whether they were landing strips or silent control towers for an alien airport—fine. There’s mystery enough to satisfy believers and Barça fans alike. They were, it seems, precursors to many contemporary initiatives.

A few days ago, volunteers restored the enormous figure of a lion carved into the hillside near Whipsnade Zoo in Bedfordshire, in the United Kingdom. Hundreds of enthusiasts stomped— with a distinctly British diligence—across the 1,100 tons of chalk that form the feline’s silhouette. Unlike the Nazca figures, this one was conceived to be seen by humans of less enthusiastic spirit. Admission to the zoo is not cheap, although its approval rating—16,757 reviews—gives it an impressive 4.5 out of 5.

They’ll say it was built as the zoo’s emblem, whatever they like, but certainly not with the same mystical devotion that shaped the Nazca lines. The lofty gazes of mountain gods have little to do with the pedestrian visitors of the zoo. The Whipsnade lion is a monumental marketing gesture, a billboard on a hillside, a spontaneous homage to Irish step dance, tap, and flamenco footwork.

As a marketing strategy it's not as pioneering as Nazca either, but it has its years. The lion was designed by R. B. Brook-Greaves in 1930—or early 1931, since construction began in November. By April 1932, its general outline was already visible on the slope. It was completed in the spring of 1933, becoming the largest chalk figure in England. During World War II, the lion was covered to prevent its silhouette from serving as a reference point for German pilots. In May 1981, to celebrate the zoo’s 50th anniversary, it was illuminated with 750 bulbs, transforming for a single night into a gigantic glowing patch. Owen Craft, the zoo’s general manager, is proud of the lion and celebrates that its restoration has returned its original brilliance.

The Cerne Abbas Giant, that 55-meter naked colossus brandishing a club on a Dorset hillside, is perhaps the most provocative and enigmatic figure in the British landscape. Its origin lies somewhere between mythology and satire. Some see in it an echo of Helis, an Anglo-Saxon deity; others argue it is a late incarnation of Hercules; and there are those who insist it was carved during the English Civil War as an explicit mockery of Oliver Cromwell. Its famous anatomy—cited as often as it’s photographed—may be due to a Victorian error or excess, an attempt to fuse, in a corrupt burst of design, a tiny penis with what might once have been its navel. A naked hero who is not Greek is a rarity, and Greek heroes, as we know, were never well endowed. This one provokes blushes and prudery. Even a bar in Parliament grants him a fig leaf to preserve institutional respectability.

For centuries, the British soul has shown a certain inclination toward carving enormous figures on hillsides—probably because it is a markedly undulating country, lacking flat, comfortable surfaces.

Such disproportionate figures dot many of its hills. Horses, giants, and lions condense thousands of years of landscape, myth, and dubious practical utility. The Uffington White Horse, for instance, more than three millennia old, points to a ritual origin linked to fertility deities; the Cerne Abbas Giant wavers between pagan memory and political satire. All share a tacit purpose: to turn the landscape into a canvas upon which a faith—and a monumental pride—can be reaffirmed.

The Uffington White Horse, in the Berkshire Downs, is the oldest of all the hill figures and has received uninterrupted care for three millennia, since its creation in the Iron Age. Soil tests place its origin between 1200 and 800 BCE, and around it proliferate legends ranging from sleeping dragons to the improbable awakening of a resurrected Arthur. Some suggest the animal is not a horse but a stylized dragon, an idea encouraged by the proximity of Dragon Hill and by similar figures found on second-century BCE Celtic coins. For historian Mark Hows, however, the silhouette clearly evokes the Celtic goddess Epona, protector of horses, and indeed the other two dozen or so chalk horses scattered across Great Britain may be nothing more than imitations—or late echoes—of the Uffington original. Of all of them, only the Osmington Horse, carved in 1808 to honor George III, includes a rider. Its own story offers an ironic twist: in 1989, a television program attempted to “restore” it and ended up damaging it, forcing a proper repair ahead of the 2012 Olympic Games, when it shone once again before millions of viewers.

Comparing the Nazca figures to these English doodles is hardly fair. It is no coincidence that the former enjoy universal recognition. And yet, what they share—what is fantastic—is humanity’s transcendentalist will. Despite the absurdity of outlining something that could someday be condemned by some collective claiming that the lion is part of the cultural patrimony of Africa’s colonized peoples, the volunteers devote themselves to the task with devotion. Because it lies in human nature to confront and emulate the divine.

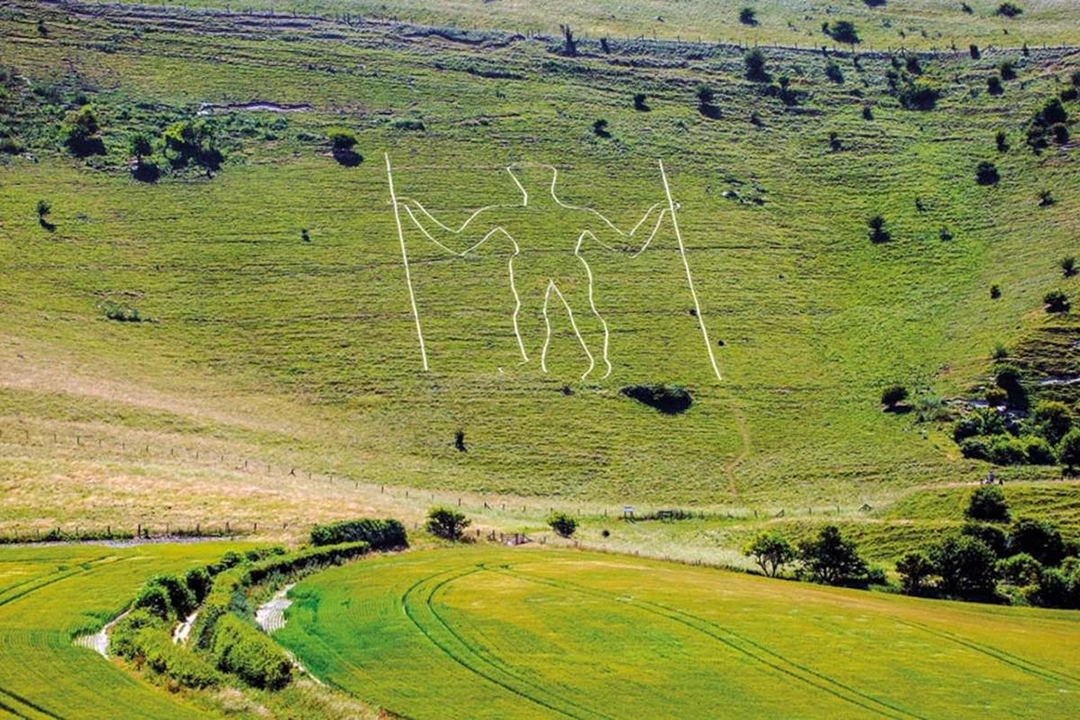

In Wilmington, East Sussex, rises the Long Man, a figure far more restrained than its exuberant cousin in Dorset. Until the nineteenth century it could only be seen when the sun struck at a precise angle, but since 1874 its silhouette has been fixed with yellow bricks, permanently revealing this “mysterious guardian of the South Downs,” as the Sussex Archaeological Society describes it. Its origin is as disputed as that of any prehistoric figure. Some consider it ancient; others argue it was the work of an artist-monk from the nearby priory—placing it between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries—and still others connect it to the fourth century thanks to Roman coins bearing similar figures. It has even been compared to an armored figure found on Anglo-Saxon ornaments. The truth, for now, remains beneath the grass and chalk.

Comments powered by Talkyard.