Image from 'Biography: 19th Century photographer of Snowflakes – Wilson Bentley.' Monovisions. Black & White Photography Magazine. July, 2018

It is 18 degrees in Cincinnati right now—remarkably close to the record high for a December 26: 20 degrees Celsius, registered in 2016. No snow. It would be tempting to invoke climate change if I were looking for a quarrel, but I’ve just come off several days of snow. I lack serious arguments to do so.

Snow is beautiful, as are snow-covered landscapes—especially when the sun is out and the air stands still. In New York, where temperatures today are far colder, our Martí left behind several reflections on it. He associated snow with moral estrangement, with the exposure of the exile, and with the North’s severity when set against the warm memory of Cuba. In his North American Chronicles, he observes how snow cools the city while at the same time stripping it bare: rather than concealing, its white mantle lays bare inequality, poverty, and the loneliness of immigrants. The urban landscape, far from being ennobled, becomes harsher, more hostile.

In the autumn of 1884—on October 20—he drafted that famous letter to Máximo Gómez, in which he left us one of his enduring sentences: “A nation, General, is not founded the way one commands a camp.” His heart must have been burning then. How not to imagine him anxious, sketching the foundations of an imagined republic meant to stand on its own, through its institutions. His heart burned, trampled and resolute—and so did he.

In those same days, both frozen and incandescent, some four hundred kilometers away, in Jericho, Vermont—where Ana de Armas now rests in a residence with six bedrooms and eight bathrooms—a nineteen-year-old named Wilson Bentley observed ice with fascination. He broke it into tiny fragments and placed them under a microscope. He wanted to know what lay inside. So many experiments led him, the following year, to achieve the first photographs of individual snowflakes. Like the Apostle, he too burned. His hands, however, remained cold.

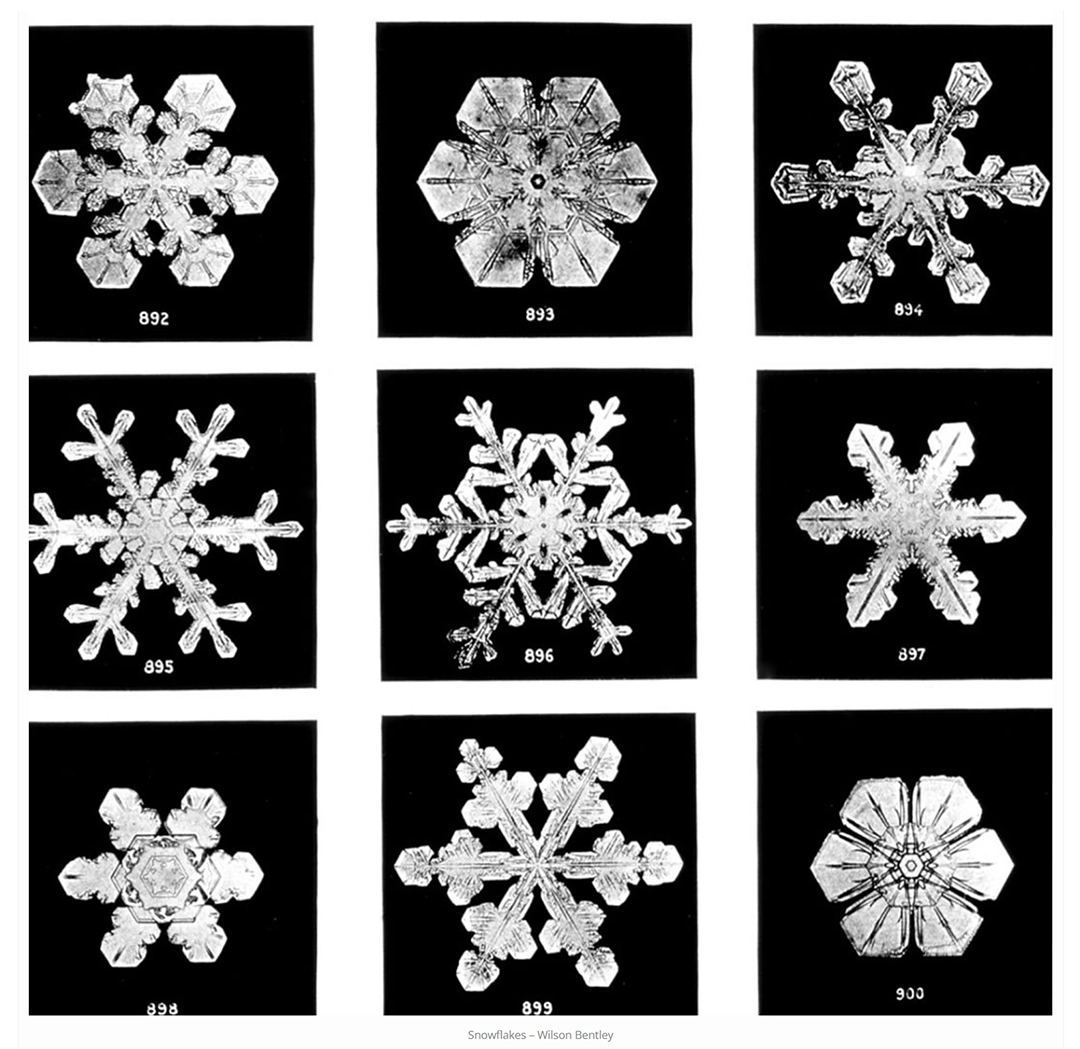

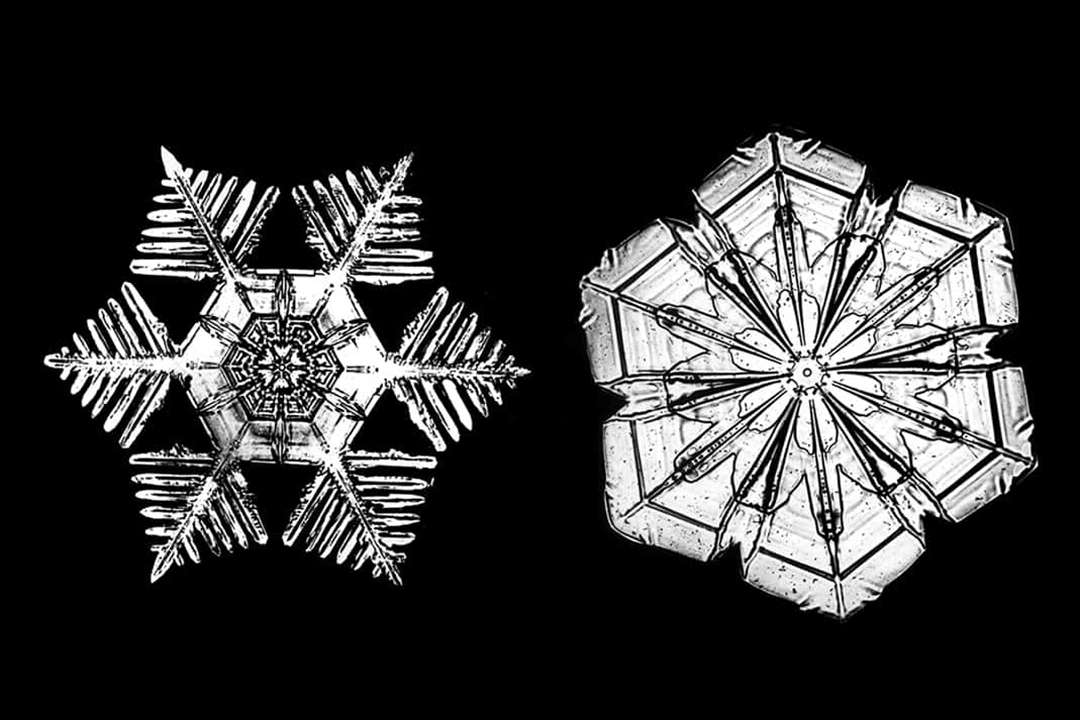

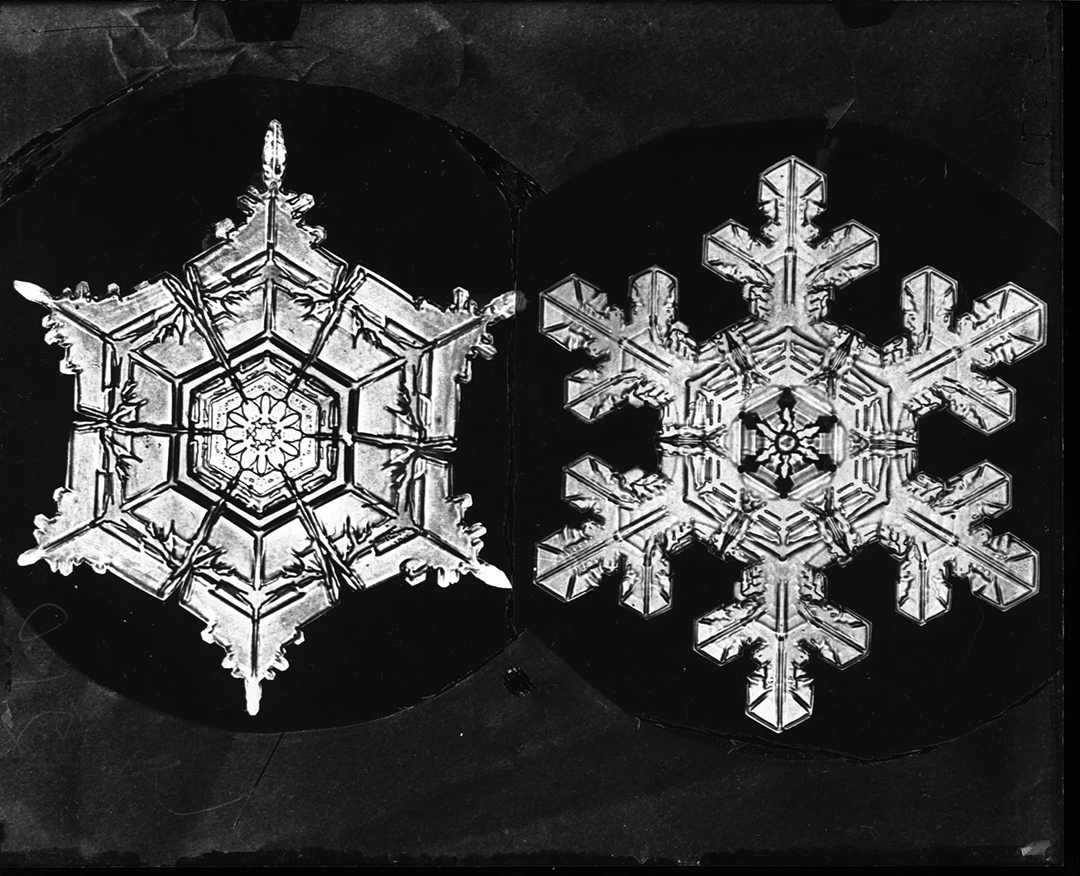

He realized he could never find two identical snowflakes, despite spending nearly the rest of his life photographing them. He produced more than five thousand images, devising ingenious techniques to slow their melting—such as capturing them on chilled velvet—and to reveal their complex hexagonal geometry.

A selection from Snowflake Bentley’s work. Photo from the Wilson Bentley Digital Archives of the Jericho Historical Society

In 1931 he published Snow Crystals, a foundational work for understanding the forces involved in their final design. To this day it remains an indispensable reference for meteorology, the physics of ice, crystallography, and, more broadly, for materials science and the history of scientific images.

The reason we recall his story today is that, beyond scientific rigor, his studies reveal an exquisite aesthetic sensitivity—the poetic expression of mathematics. Humanity thus came to know something singular and extraordinary that nonetheless had no practical use: that each snowflake is unique, that each is a crystalline treasure, a flower of extreme beauty and fragility.

Most of his magical images remain on view in his hometown, while the Natural History Museum in London preserves the digital archive. They are as marvelous today as they must have seemed more than a century ago. He himself, upon dying—still with frozen hands—remarked: “What delight awaits all future lovers of snowflakes and of beauty in nature!”

A selection from Snowflake Bentley’s work. Photo from the Wilson Bentley Digital Archives of the Jericho Historical Society

A small, scientific postscript

The shape of snowflakes is neither accidental nor the result of an aesthetic intention, but of an inevitable physical process. When water freezes, its tiny particles organize into a six-sided structure that repeats itself again and again. As the flake falls, it grows and is affected by cold, humidity, and the air it passes through. These variations make each one slightly different, yet they never violate the basic form. Six sides—never five, never seven. This is why all snowflakes resemble one another and, at the same time, none is the same. Their symmetry is the outcome of a simple, constant natural process. Minor differences do appear, but they ultimately continue along a single path.

When next year you cut out snowflakes for your Christmas tree, count the points carefully: six, always.

A selection from Snowflake Bentley’s work. Photos from the Wilson Bentley Digital Archives of the Jericho Historical Society

Comments powered by Talkyard.