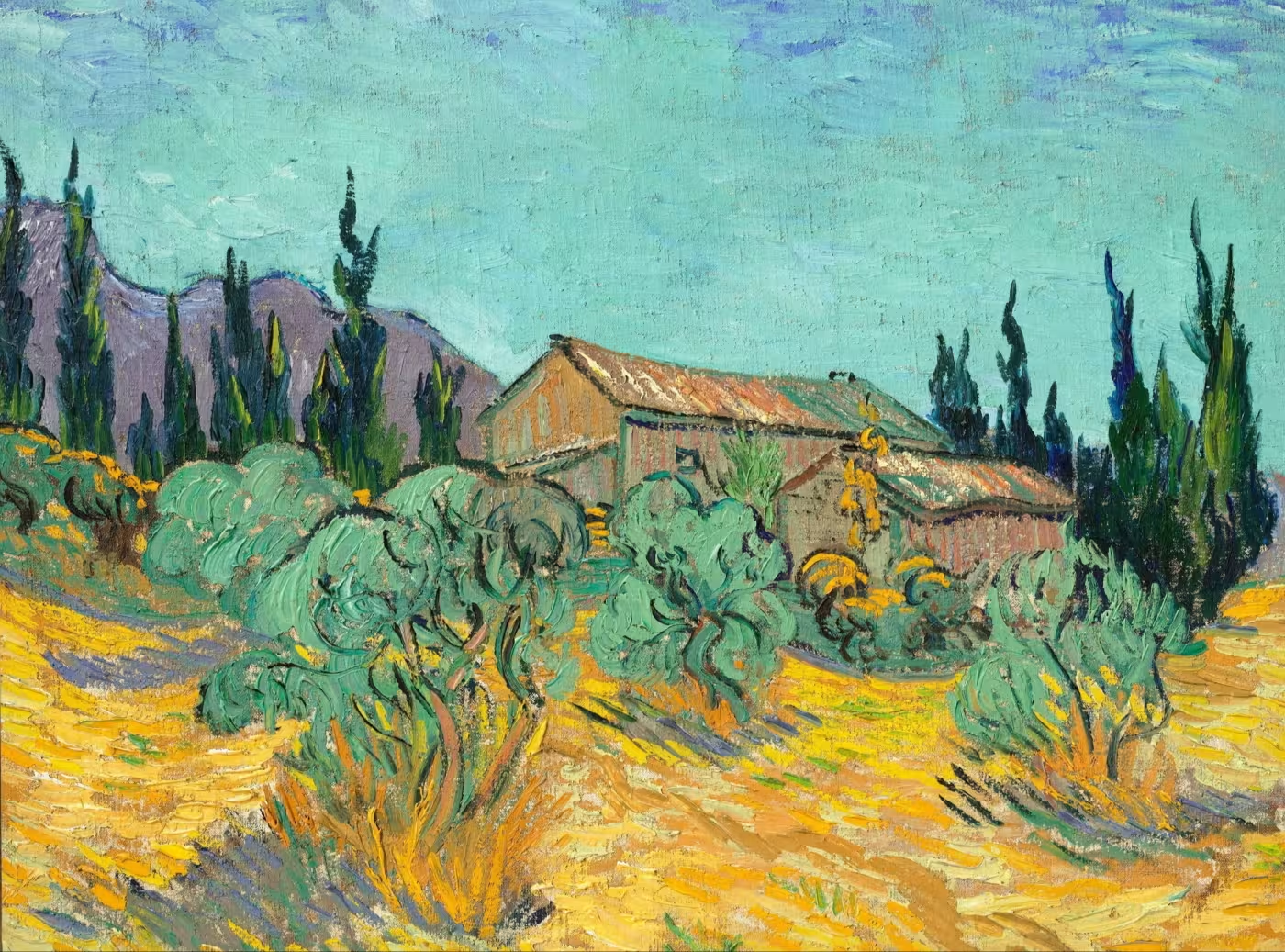

‘Cabanes de bois parmi les oliviers et cyprès’ (1889) by Vincent van Gogh was acquired by Beaumont Nathan for $71 million at Christie’s in 2021 © 2021 Christie’s Images Limited

The art market revolves around monumental sums. What captures the spotlight is usually the excessive sale, the broken record, the news that one artist or another has climbed the rankings. The tip of the iceberg. Behind these dazzling transactions lies the effort, talent, and dedication of one of its key figures: the advisor. A specialist who assumes he will never shine before the public, though he is the one who prepares the ground for a mechanism sustained by fascinating yet essentially deceptive flashes. What reaches the outside gaze are headlines taken over by auctions and artists—whether alive or long gone. One could say we are left out of the game, that the party was conceived for a different class of people.

Suppose fortune hands me a lottery prize and, after the inevitable expenses, I am left with a few spare millions. If in some reckless fit I wished to buy myself a Van Gogh without pretensions—what would be the first thing to do? Hire an advisor, of course. First, because I have no desire to enter an auction and clash with emissaries of glittering fortunes. I prefer a relatively discreet operation. I have some notion of what a Van Gogh costs, but I do not know which, among those that might be obtained for a “mere” few millions, would be the best option—and whether it is also free of the suspicion of forgery. Minutiae, yes, but decisive. There is a long stretch between taking a piece down from where it now hangs and placing it on the wall of my new apartment.

Henry Wyndham and Melanie Clore, founders of the advisory firm Clore Wyndham © Nick Harvey / Shutterstock

It will unleash oppressive, cryptic paperwork and a frenzy of activity. The advisor will be the one to clarify the bureaucratic tangle and survive the intensity of all the stakeholders involved. Perhaps that is the essence of his craft: to hold the buyer’s hand and decode what a piece is truly worth beneath the veils of fashion and speculation. The moment the first step is taken, the transaction becomes a labyrinth of prices, provenances, taxes, and inheritances. The advisor works like a guide who, in silence, translates confusion into clarity and direction.

Art, in its most authentic form, should speak for itself. Yet the market has manufactured countless filters that end up diverting attention toward everything surrounding the piece: the roll call of former owners, the historical prices, the chain of sales. All of it wrapped in the sophisticated label of provenance.

The advisor frees the collector from such torment and allows him to focus on the essential. Which will not always be the genuine enjoyment of a work that has long moved him. It may be an investment, a way to shelter capital from inflation, or a matter of many other motivations. The true encounter with the piece, within the intimacy of one’s own space, comes only when the moment is right.

Lateefa bin Hamoodah, Beaumont Nathan’s regional advisor for the Middle East © Charles Shearn

Such professional interventions are not confined to spectacular acquisitions moving in the millions. In almost every case they prevent mistakes, open doors to works previously out of reach, and mediate in processes where family emotions obstruct decisions about inheritance. Art is not only passion or money. Often it is heritage, symbol, and memory. And when all of this collides and creates a logjam, a lucid, dispassionate mind must mediate between the pulls of the ideal and the weight of reality.

As those well versed insist, the due processes of the art market cannot be navigated without the guidance of an expert. For it is a circus that has little to do with the mystery of art or of a single work: it has its own. The market must persuade, implant in the collective consciousness the notion that a piece of canvas, soaked in oil, is worth millions—and to do so it must act as a dark magician, implacable and ruthlessly sophisticated.

In the face of that storm the modest buyer and the artist are like butterflies, and the work itself a little flower battered by the wind. And so, if we are to pay millions for that canvas, then it is worth paying for sound counsel as well—for the guide who can find firm ground in a swamp or a passage through frozen mountains. The one who can turn uncertainty into a habitable space. That is probably his true value: to cast light upon the hypnotic and sometimes schizophrenic world of the art market.

Alice Black (left) and Tatiana Cheneviere, co-founders of Black + Cheneviere

Comments powered by Talkyard.