Go to English Version

Go to English VersionA few weeks ago, a post appeared on my Facebook feed from the Beagle Freedom Project, celebrating the seventy-fifth anniversary of Snoopy — perhaps the most universal of all beagles. Since 2010, the Beagle Freedom Project (BFP) has been rescuing, rehabilitating, and rehoming animals once used in research laboratories. The initiative was born of people who, for some reason, paid special attention to this breed — probably for its docility and its good-natured temperament. Beyond rescuing dogs, they also promoted the Beagle Freedom Bill, a legislative effort — now adopted by several states — requiring that animals be released after testing rather than euthanized.

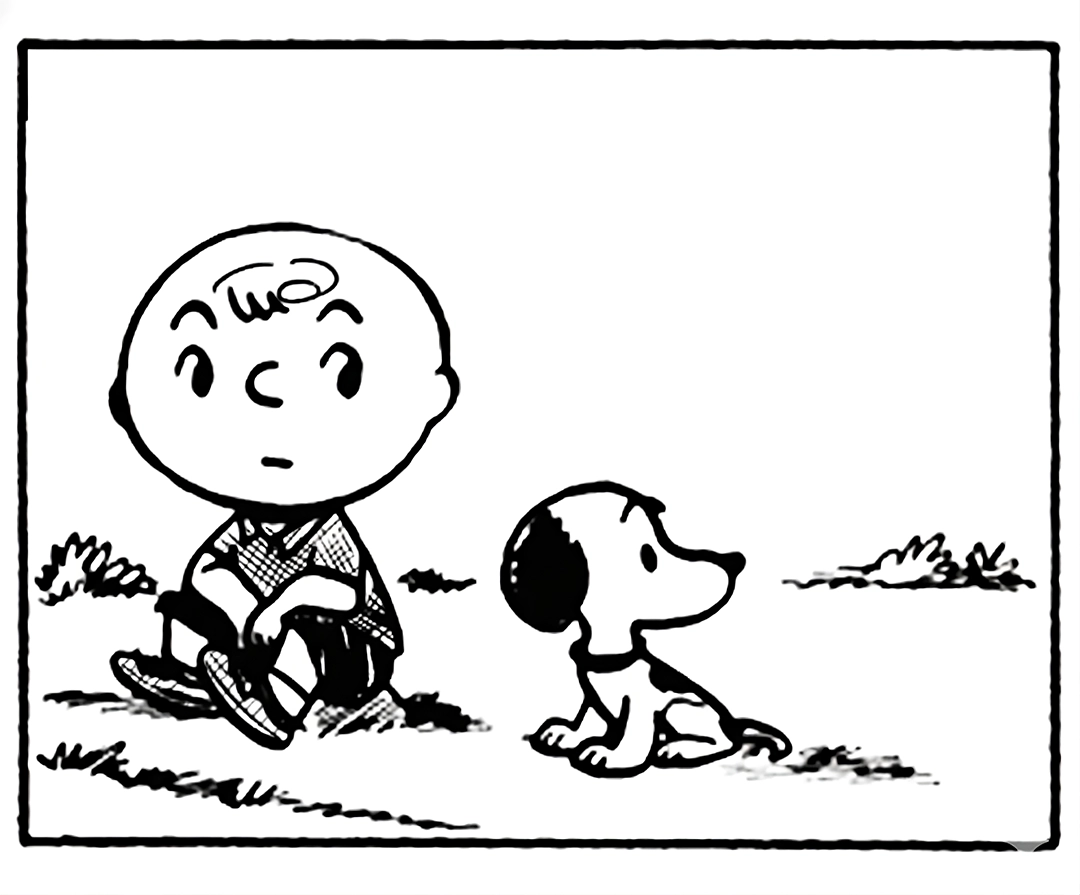

Snoopy would have been among the first to be adopted. He is, after all, an exceptionally charming beagle. The breed, of British origin, is known for its steady temper and playful spirit. Charles M. Schulz took inspiration from a real beagle named Spike — his childhood companion — when he created the character. Whether Snoopy really looks like a beagle is irrelevant; his design is stylized, a free artistic interpretation in which what matters is not biological fidelity but temperament — the expression of character over breed.

Snoopy first appeared on October 4, 1950. Conceived as Charlie Brown’s dog, he remained so for a while — until his own narrative gravity made him independent, transforming him into the true axis of the strip.

Unlike other illustrious comic-strip pets, Snoopy possesses — or seems to possess — an unfathomable interior life. Perhaps he doesn’t, but it feels as though he does. And we will never really know. Without fanfare or strain, he evolved into a global icon of popular culture.

He has appeared on television, in films, in advertising, and even in music videos. NASA adopted him as a symbol of safety in its space missions, granting astronauts the Silver Snoopy Award — a small talisman of perfection and vigilance.

Silver Snoopy Award by NASA

Snoopy embodies imagination, irony, and the dream of escape — traits millions of readers and viewers recognize as their own. Through endless merchandising, theme parks, and charity campaigns, he has become a bridge between nostalgia and the everyday freshness of humor. In that sense, Snoopy stands between the comic strip and real life — a figure that radiates tenderness while delivering, through candor, a subtle social critique. Graphic art, at its best, leaves such traces on our collective memory.

He stands at one corner of a symbolic quadrangle, whose other three vertices are his red doghouse, his typewriter, and his alter ego as a World War I flying ace. Together, they are universal references — archetypes that have inspired generations of artists, designers, and dreamers.

I remember the first time I saw Snoopy — or, rather, the earliest memory I retain of him. At home we had a Soviet television set, a Rubin-207, which required a long ritual of warming up before it would awaken. I must have been seven or eight years old, devoting long idle hours to its flickering light. What I can recover from that haze is a childish dilemma: I wanted to be both Snoopy and Charlie Brown — and, at the same time, to keep Linus van Pelt’s blanket. That security blanket seemed to ward off evil, wakefulness, and the adult world itself.

I remember even more clearly the moment, many years later, when Snoopy ceased to represent a kind of affection and became, for me, a desolate semiotic sign. The culprit was Umberto Eco. In his Postscript to The Name of the Rose, in a chapter titled “The Mask,” he begins the second paragraph with these words: How can one say, ‘It was a beautiful morning at the end of November,’ without feeling like Snoopy? Then he adds: And what if I had made Snoopy say it...?

My poor beagle was devalued, and I ended up seeing him as the emblem of a solemn simplicity and a profundity rendered utterly innocuous.

Originally, the comic strip was aimed at the readers of 1950s daily newspapers: adults and young people with a middlebrow cultural education, accustomed to humor and social commentary in print. Yet the simplicity of the drawing, the tenderness of Snoopy, and the innocence of the children made it irresistibly appealing to younger readers as well.

In those same Postscript pages, Eco confesses that his novel offered multiple levels of comprehension, depending on the reader’s cultural formation. So does Snoopy. He can amuse the casual reader seeking warmth and gentle humor, while simultaneously engaging a more cultivated audience — one capable of reading his metaphors of solitude, frustration, dreams, and the contradictions of life. Today it’s difficult to say which social group finds him most interesting. I would wager children from ten upward to adults in their forties. Those over fifty probably identify less with the dog than with the child they once were.

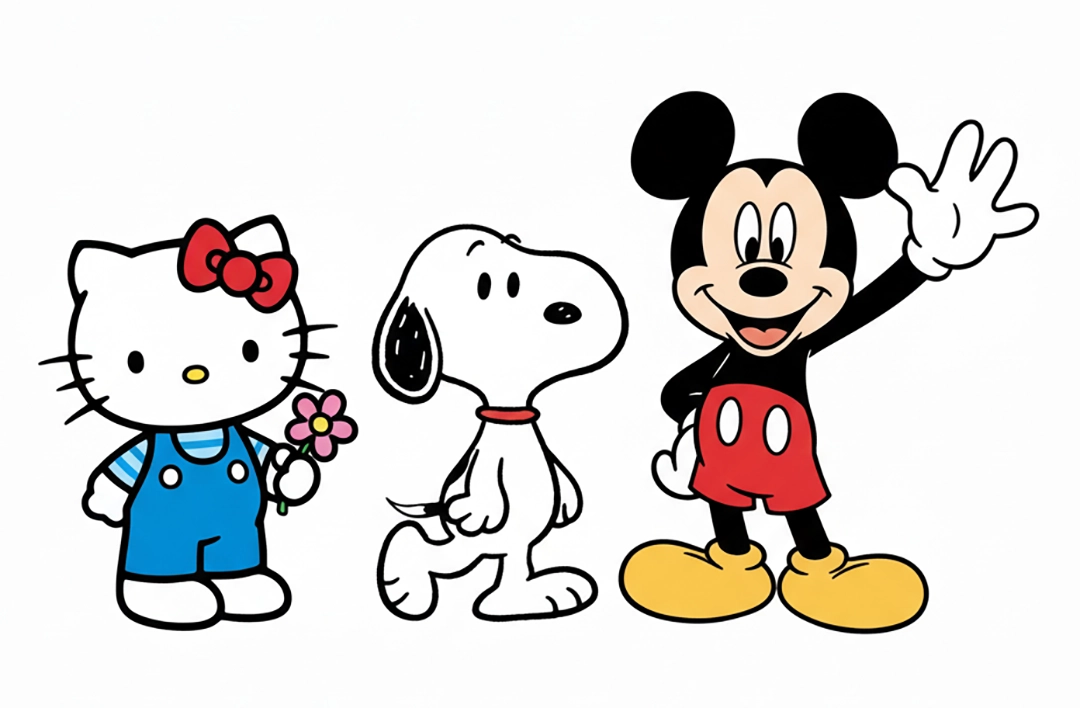

In any case, Snoopy occupies the highest tier of the universal cultural altar — surpassed only by Mickey Mouse and Hello Kitty, who, though far more ubiquitous, lack his symbolic depth. Our Snoopy, beyond his popularity, reveals to the attentive eye a complex and multifaceted personality, endowed with an intense inner life shaped by fantasy, creativity, and the impulse to escape. His relationship with Charlie Brown oscillates between loyalty and irony, between affection and critique. His humor and self-awareness turn frustration into symbolic play. Beneath his mask of autonomy glimmers a quiet existential anxiety, expressed through his failed writing and his impossible dreams of glory and universal recognition.

Taken together, Snoopy is a psychological archetype of imagination as refuge — a being who embodies the human capacity to reinvent oneself in the face of everyday adversity. He unites the tenderness of a faithful companion with the irony of a detached observer.

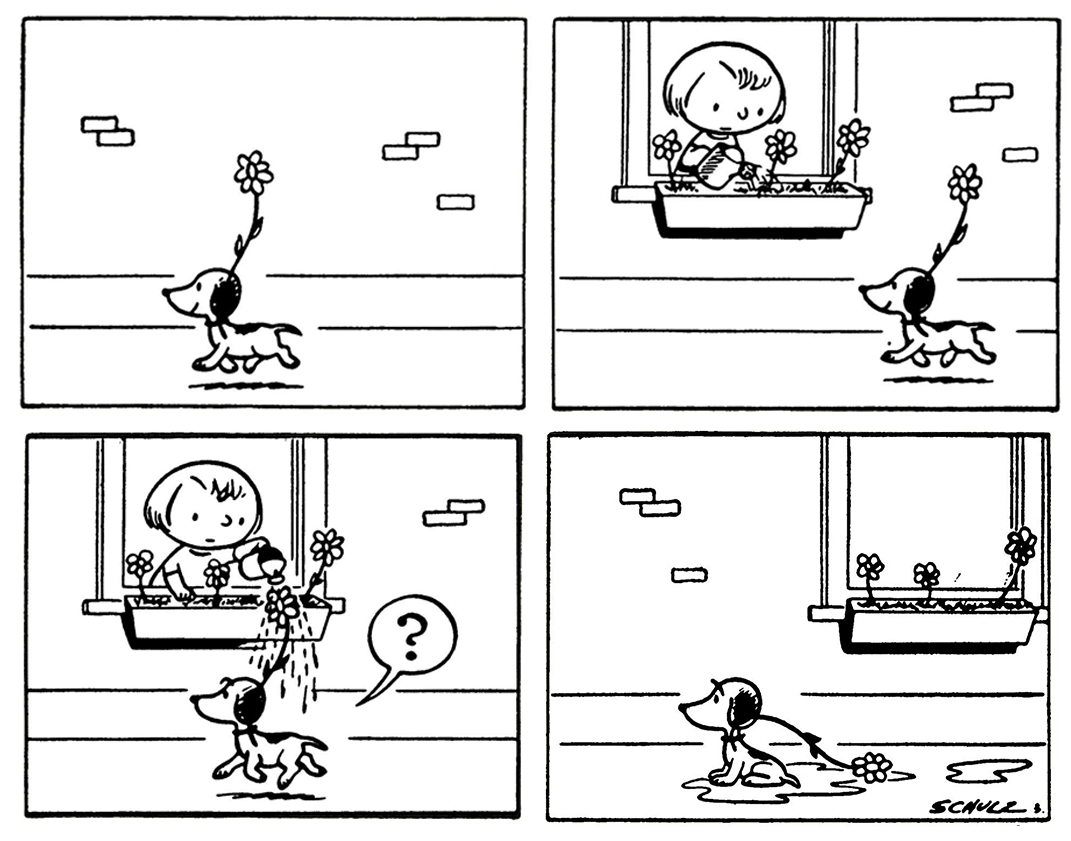

As a final anecdote, it’s worth remembering that Snoopy began by behaving like any other dog: walking on all fours, jumping, begging for scraps. Schulz gradually transformed him — first granting him thoughts (in word balloons), then seating him atop his doghouse, and finally endowing him with an entire imaginative universe that made him the undisputed protagonist of the Peanuts world.

As I was saying, he appeared on my feed — and later, privately, printed on a pair of pajamas in one of those casual photos that, if you let them, can leave you longing for a future that has already passed, and a past that has yet to arrive.

Comments powered by Talkyard.