Go to English Version

Go to English VersionTrying to find something even mildly interesting on the platforms for a quiet December night, I stop at what appears to be the latest cinematic version of the mythical Superman. I read that it was written and directed by James Gunn and released last July, just this past summer. I also note that it has enjoyed a favorable reception from both critics and audiences. A commercial success, in fact—the highest-grossing solo Superman film in the United States among those that place the superhero at the absolute center.

In an interview, its director stated that Superman is “an immigrant that came from other places and populated the country…” All hell broke loose. Troy burned. X burned. Woke nonsense, great job, leftists… the worst people on the planet. Compliments of that kind. Gunn had already provoked Donald Trump and his infantry, and he made those remarks in the middle of a summer marked by raids carried out by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

To be honest, almost all of us had overlooked the obvious: Superman is practically—if not entirely—an undocumented immigrant. One of the country’s supreme moral symbols is an immigrant. He did not even enter under the terms of existing legality. He did not come from one of those shithole countries one is supposedly no longer allowed to arrive from, but from Krypton—a shithole planet, in full decay and destruction. At least he arrived handsome, blue-eyed, which apparently counts as a mitigating factor.

Perhaps there is additional context that explains the virulence of the reaction.

Superman was conceived by the sons of two Jewish immigrant families. Jerome “Jerry” Siegel, whose parents emigrated from Lithuania to New York in 1900, and Joseph “Joe” Shuster—whose family moved from the Netherlands to Toronto. They met in school, right here in Ohio, and quickly realized they shared something in common: the rest of the students picked on them.

They projected into their imagination a figure that might free them from their small personal tragedies. An American from elsewhere, who would confront bullies and defend the oppressed. His alternative identity, his mimetic character—the journalist Clark Kent—would even be shy, inconsequential, and would wear, like Siegel himself, prescription glasses.

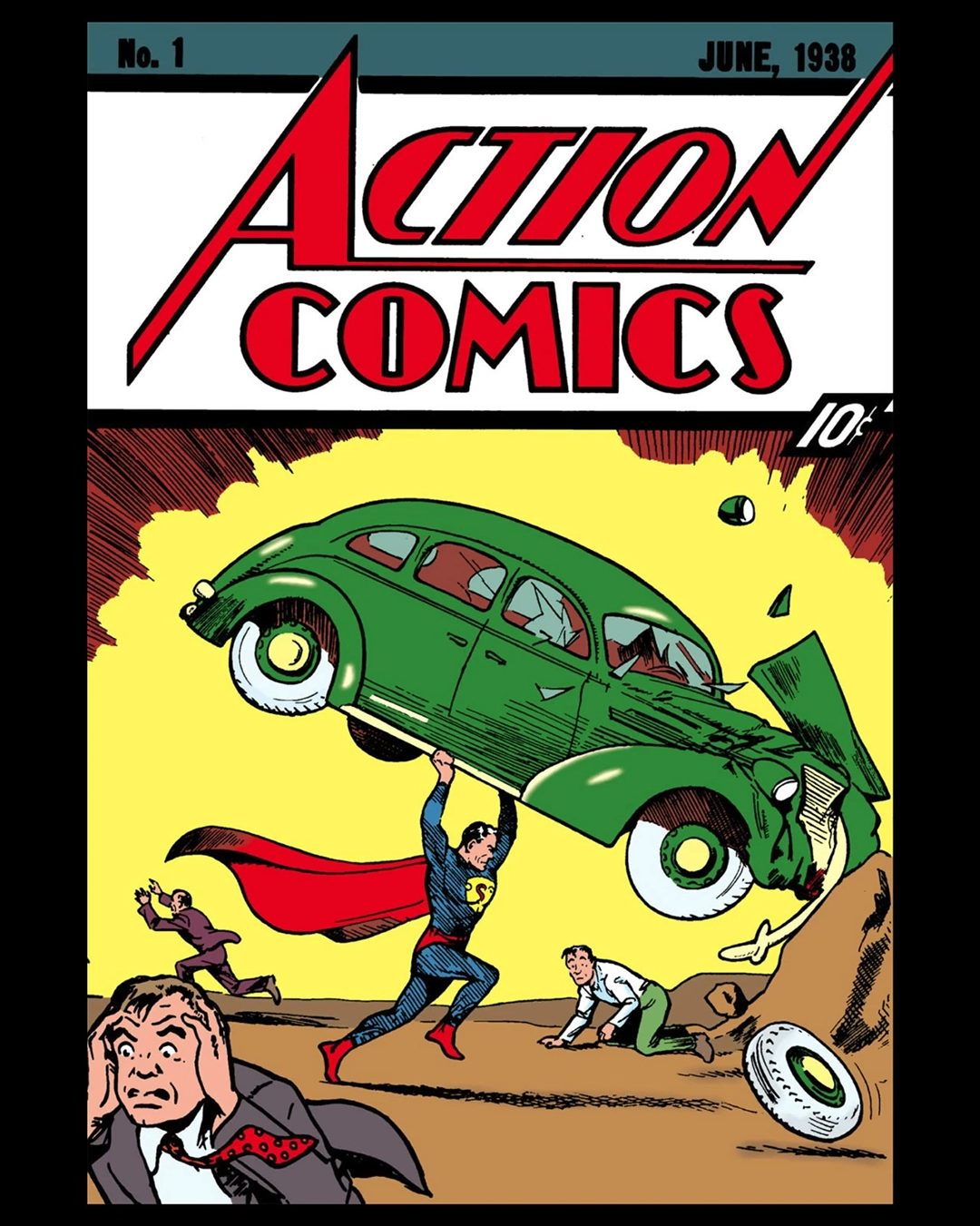

It was impossible to foresee the impact of that first issue of DC’s Action Comics, published on April 18, 1938, with Superman’s arrival. He was not among the earliest heroes of comic books—Doc Savage or John Carter of Mars precede him, for example—but he was the first endowed with supernatural powers, the first super. On that cover he was already smashing a car against a rock while the villains fled in terror. It was a cataclysmic moment that gave birth to an entirely unprecedented cultural modality, one that would weigh as heavily as few others on the collective imagination: the concept of the superhero.

Over time, contradictions arising from his dual nature would only multiply. Because this character embodies, like no other, the paradox of possessing superhuman abilities while deliberately adopting a mask of modesty, clumsiness, and restraint. He is not defined by what he can do, but by what he chooses not to do. As an ideal—formulated time and again as truth, justice, and a vague notion of the common good—he stands on a delicate frontier between universal morality and the specific historical context that shapes him. This is why he has always functioned as a mirror of his time. When social trust in institutions is strong, he is taken as a guarantee. When that trust erodes or collapses, he reveals cracks, contradictions, and suspicions.

This intermittence can be considered essential, because it continually tests his nature. His identity does not depend on a specific territory but on an ethical compass. His coherence resides in adherence to it; once it is lost, all that remains is gratuitous violence and loss of control. He acts with the morality of an earthquake. His relevance does not lie in the accumulation of power, but in a fragile combination of decency, responsibility, and uprootedness. What makes him relevant—and permanently implausible—is that he chooses not to crush a world he could easily dominate.

That is what one of the many Americas that coexist believes to be its moral foundation. There are others that see him as a force to be feared, before which one must kneel—on one knee or both. A broad-shouldered white man, sky-colored eyes, wrapped in a blue-and-red maillot stamped with a logo: an entirely local production for domestic consumption, and from there, for the rest of the planet.

Over time, the cultural ecosystem may have redistributed other superpowers among second- or third-tier heroes. One might even say it is embarrassing that the rest of the communities that make up this ecosystem are underrepresented—yes, for a long time they have been—and that they sprout like mushrooms, overlap, and constantly steal attention that the burly pioneer does not require.

One page of The Definitive History depicts, in its panels, two encounters with President John F. Kennedy, published after his assassination. In one of them, JFK—through the public figure of Superman—learns his secret identity, discovering that he and Clark Kent are one and the same; he gains access to the structural datum of the myth. This does not trouble the superhero in the least: “If I can’t trust the President of the United States,” he smiles, “who can I trust?”

Can you imagine that panel today? Quite possibly another president would rush straight to social media to rant about that Clark Kent—terrible character, purveyor of fake news. And do not rule out a reminder that he is an illegal immigrant who came from a shithole planet, in a disgusting solar system with a dying, pathetic star.

Comments powered by Talkyard.