Go to English Version

Go to English VersionA few days ago, I published a review of an exhibition held in Cincinnati, where the banana—liberated from its role as a trivial fruit—rose as an object of symbolic power, invested with a political density far exceeding what its modest morphology might at first suggest.

How does a banana come to embody economic domination and veiled colonialism?

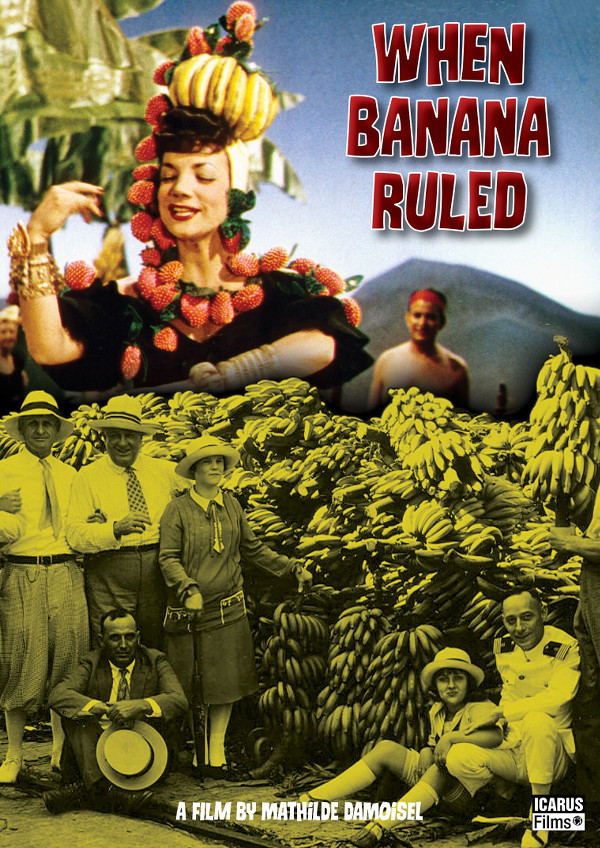

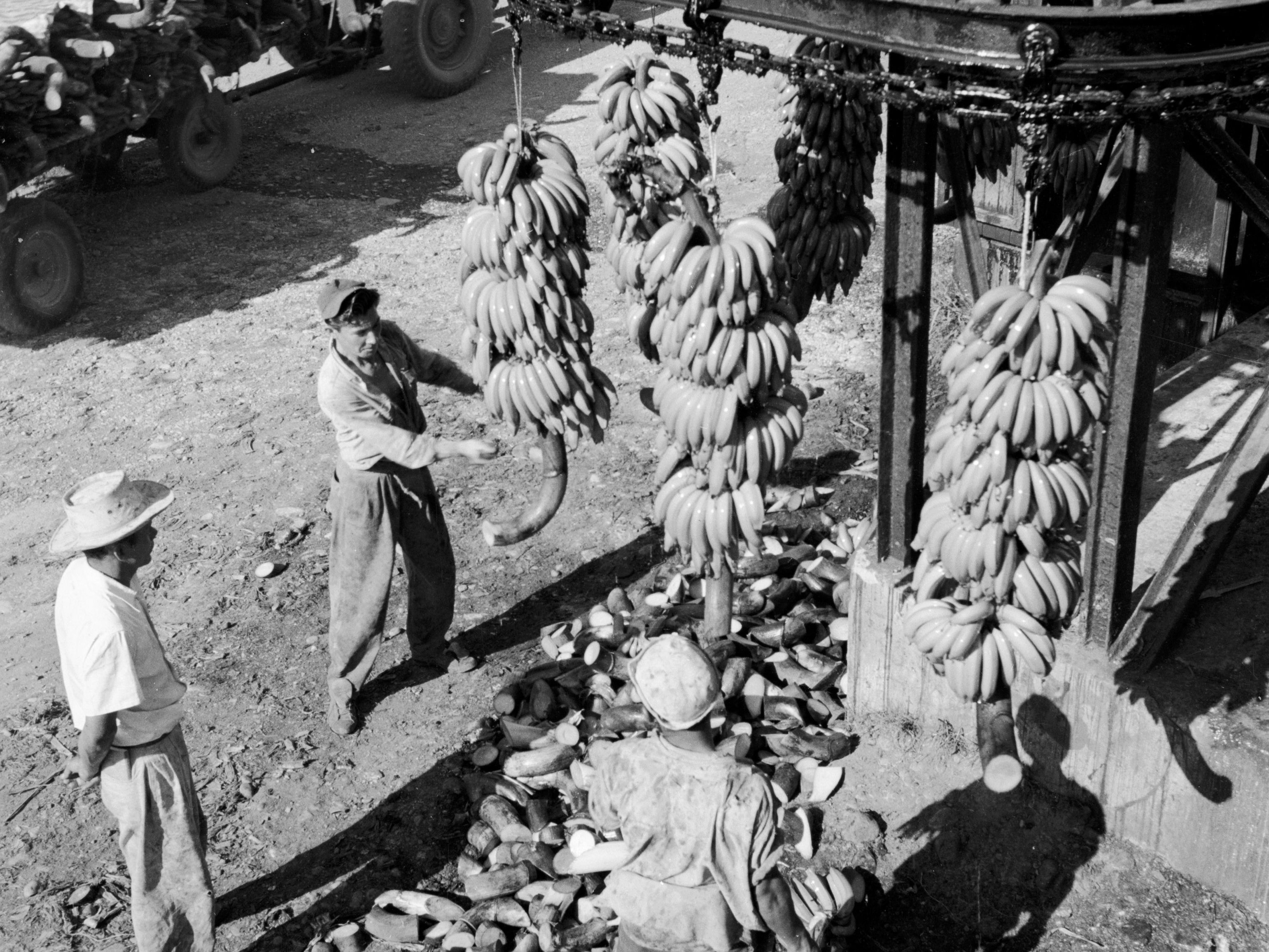

Perhaps because it stood at the epicenter of one of the darkest chapters in the history of capitalism in Latin America. In the early twentieth century, the United Fruit Company, a U.S.-based enterprise that monopolized the production and export of bananas in the region, amassed such overwhelming economic power that it functioned as a parallel political force. When Jacobo Árbenz—democratically elected president—pursued an agrarian reform that directly threatened the company’s interests, the CIA, acting on its behalf, orchestrated a coup d’état that eliminated, in a single stroke, both the threat and the man who embodied it. Since 1954, the banana—and its cultivation—has carried with it a long string of turbulent connotations. Out of this history was born, with all its scorn, the term “banana republic.”

Glorious Victory (Spanish: La Gloriosa Victoria) is a tempera-on-canvas painting by Mexican artist Diego Rivera, created in 1954. The painting addresses the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état that the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) backed to overthrow the democratically elected Guatemalan president Jacobo Arbenz. It is held at the Pushkin Museum, in Moscow.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glorious_Victory#

But bare politics do not interest me. To confine the venerable banana to that insipid register is to close the door on a symbolic feast of the highest order.

During my years at the Institute of Design, I took a course devoted to the basic strategies of advertising and the design of mass-produced objects. The professor, whose clouded gaze recalled a faded Rodolfo Valentino, liked to insist that nothing was more phallic than the deodorant tube sitting on the bathroom shelf—especially the ladies’ kind. They had, he claimed, been conceived to stir desire from the unconscious, appealing as much to touch as to sight. To handle it without inhibition produced, somewhere in the mental substrata, an illusion of control, a flash of sensuality born of the precision of the grip. Its status as an everyday object allowed it to disguise its eroticism under the pretext of functionality, so that lifelong innocents could indulge in a possessive, even exhibitionist handling without the faintest sense of guilt. Disguised as necessity, the little tube awakened latent desire.

Garnier aerosol can measuring 7.4 inches (18 cm) alongside a Dove Ultimate Dry Spray deodorant, showing the difference in height and format between the two products.

And the banana—which one is meant to put in the mouth—what, then, are we to do with it?

We might as well begin at the beginning. Strangely enough, the banana is not American: it originated in Southeast Asia and, after many stops along the way, arrived in the Americas in the hands of Portuguese and Spanish colonizers. From Brazil, it spread like a fertile weed across the continent. It adapted to the New World with astonishing ease, becoming not only a dietary staple but a fetishized commodity. Its domestication was as silent as it was efficient: in barely two centuries it had gone from exotic fruit to strategic monoculture.

In 1876, it reached the United States. During the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, it was presented wrapped in tinfoil and sold at ten cents apiece. For the vast majority, it was their first encounter—some even dared to taste it. Associated with legendary tropical climates, it arrived swathed in curiosity, yet its suggestive anatomy also aroused a certain unease. True to the Victorian values of the nineteenth century, it was deemed a problematic food, particularly for women. Its elongated, cylindrical form—more erect than today’s common Cavendish variety—rendered it an object saturated with meaning, indigestible to the corseted codes of bourgeois decorum. To peel a banana in public, bring it to the mouth at a right angle, or even simply hold it could be read as a lascivious act.

Its expansion in the United States cannot be understood without acknowledging its legendary will to control: over the female body, over popular taste, over the countries that cultivated it. What began as a strange and suspect fruit was, over time, domesticated by an arsenal of images, jingles, packaging, and tropical pedagogy. And yet, a mere attentive glance is enough to make the original tension resurface: its shape, its scent—everything about it remains an inexcusable provocation.

This fraught relationship with the banana lends itself to fertile reading in the realm of classical psychoanalysis. For Freud, objects charged with phallic value are not merely visual or cultural: they are structural symbols. The phallus, more than the penis, is an emblem of power, of lack, and of desire. Hence his most controversial thesis: upon discovering sexual difference, the girl believes she has lost it—or never possessed it—thus entering a “castration complex” in which absence becomes both trauma and object of desire. The boy, realizing he possesses a differential sign, immediately begins to fear its sudden loss, the possibility of failing to develop it fully, or the inability to wield it as a standard.

Such lacks, far from being physical, form the engine of desire: we yearn for what we believe we lack, for what we think will complete us, for what is never wholly within reach. That impossibility shapes our very relation to the world.

Lacan softens the argument: the phallus is not a tangible object but a signifier. What we lack is what we imagine “the Other” possesses—recognition, plenitude, and, above all, a place in another’s desire. In this terrain, gender dissolves into a single structural absence. Thus, when we grasp a banana, we do not—deep in the catacombs of the unconscious—hold a mere fruit, but an instrument of power, a device for validation. And yet, the fleeting illusion of plenitude slips away at once, relocating itself to another site from which it will continue to dictate our actions.

Almost any object can be invested with similar phallic value: a microphone, a sword, a stick of deodorant. They trigger displacements, projections, repressions. To peel a banana may seem banal or provocative depending on the symbolic script of the observer or the one performing the gesture. And, of course, the phallus can also be sublimated—transformed into a sign of wisdom, authority, fertility, or creativity. This is precisely where advertising and pop culture step in, ever ready to appropriate what the unconscious fears or covets, and return it—shrink-wrapped and gleaming—as merchandise.

Freepik is an online platform that offers graphic and visual resources—such as photos, illustrations, vectors, icons, and templates—which designers, content creators, and companies can download for use in their projects. As I am a designer, a content creator, and a business owner, I can download this image which, despite depicting nothing more than the act of eating a banana, I find myself unable to describe to a blind person.

In the end, the psyche never processes the phallic object neutrally: it associates it, fears it, idealizes it, or rejects it, according to the traces of its own desiring constitution.

How, then, did the women of its time process this natural body so laden with symbolism? Did they fear it, idealize it, reject it? Or could they, in handling the banana, avoid—if only for a moment—the involuntary stirring of their most intimate repressions?

The rest… will have to wait for the sequel.

Comments powered by Talkyard.