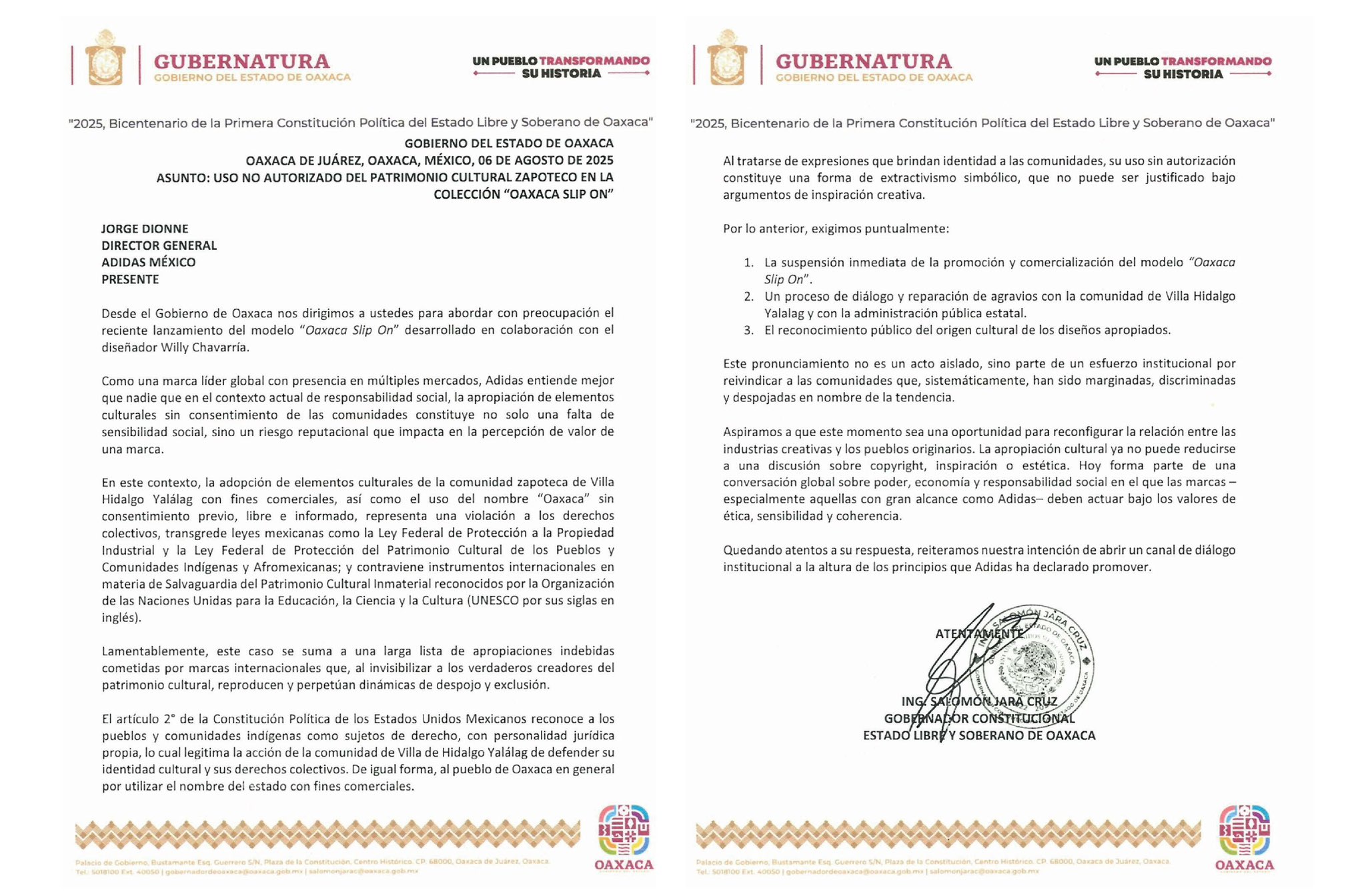

American fashion designer Willy Chavarría at the 2025 Met Gala.

American fashion designer Willy Chavarría, in collaboration with Adidas Originals, introduced the Oaxaca Slip-On, a black-molded, open-toe shoe whose aesthetic directly recalls the huaraches of Villa Hidalgo Yalálag, Oaxaca. The controversy erupted when it came to light that the shoe was being manufactured in China, and that the communities responsible for the craft had neither been consulted nor acknowledged in the creative process.

This scene plays out with the regularity of the tides. A well-known brand launches a product “inspired” by the formal repertoire of some community rooted in an “exotic” corner of the planet, and social media ignites. Cultural authorities demand justice, pronounce judgment, and the accused—be it a brand, designer, or celebrity of the moment—has no choice but to confess the sin and make a public apology.

Chavarría’s offense was to “borrow” a sandal design that huarache artisans in Oaxaca have been hand-braiding for centuries in Villa Hidalgo Yalálag. The company’s offense was to manufacture it where nearly everything produced on a massive scale is made: China. As if that weren’t enough, they placed a price tag on it bearing the Adidas logo.

Even the President of Mexico, Claudia Sheinbaum, denounced the appropriation; the Deputy Minister of Culture promised action. Adidas took down the images, sent the requisite letters, and issued an apology. Chavarría, in an act of public contrition, stated that he “deeply” regretted not having worked with the community in question, that his intention had always been to “honor,” and that he knows “love is not given, it is earned through action.”

Mexico’s Deputy Minister of Cultural Development, Marina Núñez Bespalova.

If we were to distill the concept of appropriation to its chemical essence, it is, without question, more than an academic abstraction. In its pure state, under conditions of extreme cultural asepsis, it means that those who hold economic or media power adopt—and often exhaust—symbols, practices, or creations from historically marginalized communities, profiting from them without reciprocity. Today, once again, we are looking at an everyday object transformed, almost forcibly, into an identity icon—torn from its context and reinserted into the global consumer circuit, sold with a price and a narrative that have little to do with its origins. All this, assuming one could trace it back to the universal invention of footwear.

Up to this point, the script is flawless: there is an offender, there is outrage, there is an apology, there is a promise of restitution. Yet at some point, we ought to ask: have we not spent millennia inspiring—or copying—one another? The history of art, fashion, and design is a continuum of exchange, blending, and mutation of forms, techniques, and materials. Since the day a Phoenician merchant brought purple-dyed cloth to Greece, or a Roman architect adapted Egyptian columns, we have lived in a symbolic economy where everything we now consider “authentic” was, at some point, an appropriation.

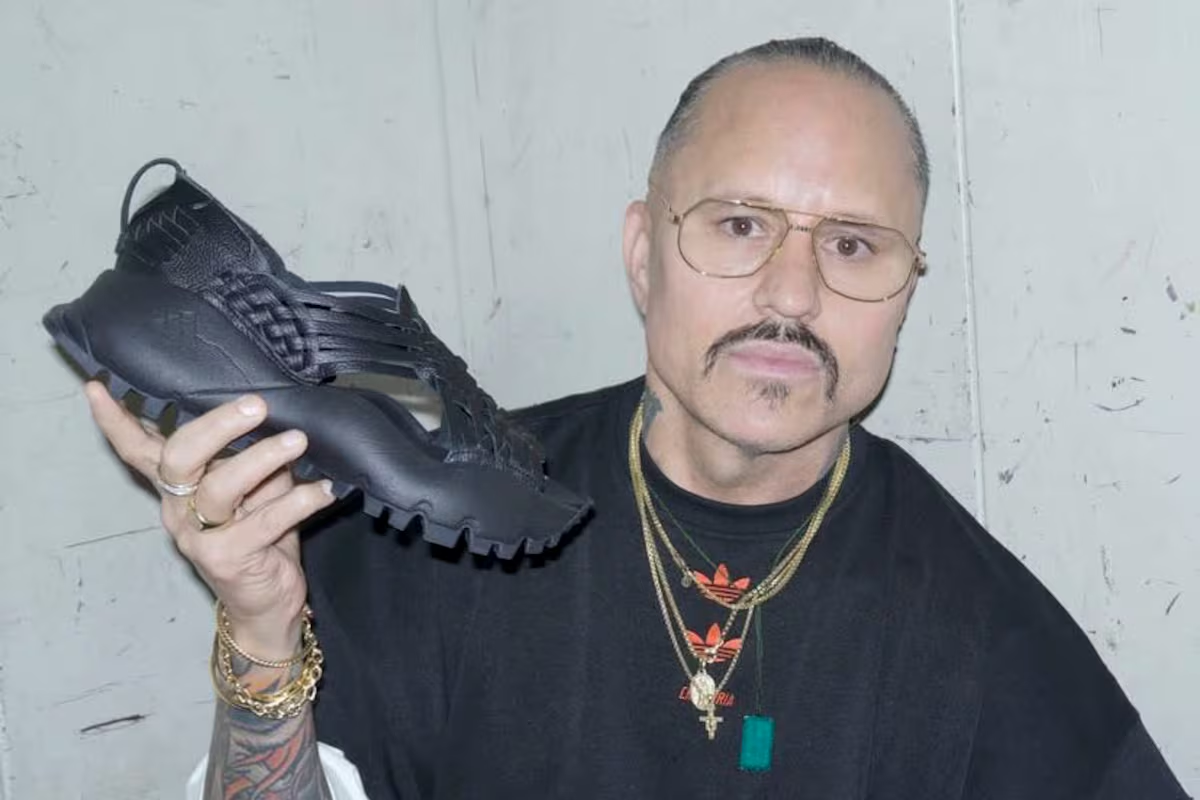

Oaxacan shoemaker Juan Aquino.

I do not seek to justify ignoring the creator communities, nor excluding them from economic benefit. But the modern economy does not work that way. The frenzied dynamics of contemporary consumer culture cannot afford to engage in endless negotiations with groups of artisans who wish—or claim—to trade, profit, or gain from many everyday objects whose origins are buried far back in time.

Perhaps the current obsession with immediate condemnation and public shaming oversimplifies a complex problem for other reasons. Oaxacan craftsmanship is by no means endangered by a pair of mass-produced sandals, just as the Mayan pyramids will not vanish because someone prints them on a T-shirt or a teacup. The real danger lies in the structural inequality that prevents these communities from negotiating from a position of strength. In any case, Adidas is bringing visibility to an extraordinary and highly distinctive form of craftsmanship, which, through exposure, increases the value of the original object.

If I were to open a pizzeria, must I seek authorization from the Italian people? And did those same Italians, when they began producing spaghetti, ask permission from the Chinese? When they discovered that both pizza and pasta went much better with tomatoes… did they ask permission from Mexico?

There is a world of difference between an object produced by an individual and commercialized without the authorization of the author or their direct heirs, and claiming the invention of the wheel, the knife, the pointed stick, bread, the milkshake, or the Spanish omelette.

The “Oaxaca Slip-On” affair is the symptom, not the disease. The scandal will fade, the shoe will become a collector’s item, and in a couple of years someone else, somewhere else, will play the same game. What will not change is our fascination with pointing the finger at the offender of the moment, even as we continue to buy, use, and admire countless things whose origins—if we were to investigate—would also have much to do with “appropriation.”

Now Adidas promises to repair the damage. The huaracheros are convinced that no industry could capture the scent of leather tanned in their land, the centuries-old tension of the hand-braided weave, or the knowledge passed from hand to hand through generations. So what, exactly, is the concern? That it be marketed as if it were an original design? What part of the Oaxaca Slip-On is not Oaxacan?

Perhaps the real question is not whether we should pursue these practices—which, in my view, have much of local marketing about them—or punish them, but whether we are willing to move beyond the spectacle of guilt and step, at last, into the less photogenic but far more effective terrain of genuine agreements, fair payment, and authentic collaboration.

The Oaxaca Slip-On

Comments powered by Talkyard.