Leni Riefenstahl

If there is something that substantially differentiates the socioliberal left from today’s woke left, it is the politics of cancellation. And if there is a figure that embodies that debate in the world of cinema, it is the German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl, author of two highly celebrated documentaries, pioneering in many ways, which she made on commission from Adolf Hitler. It is not the first time nor will it be the last time that we talk about the way of judging the relationship between art and politics.

While progressive critics of the 1980s and 1990s, such as Román Gubern or Ángel Fernández Santos, defended Leni Riefenstahl from the conviction that it was possible to separate ideology —even if it was perverse— from the aesthetic excellence of a work, the current trend leans towards a moral fundamentalism that admits no nuances. At that time it was accepted that a film could have unquestionable value even if its ideological background was reprehensible, in the same way that The Birth of a Nation is recognized as a masterpiece despite its flagrant racism. Today, by contrast, a justice-driven spirit predominates, seeking to cancel rather than to understand, to submit form to content and reduce the work to the political judgment of its author. The comparison, at bottom, reveals a change of paradigm: from criticism that valued the autonomy of art, to a cultural vigilance that subjects it to a permanent ethical tribunal.

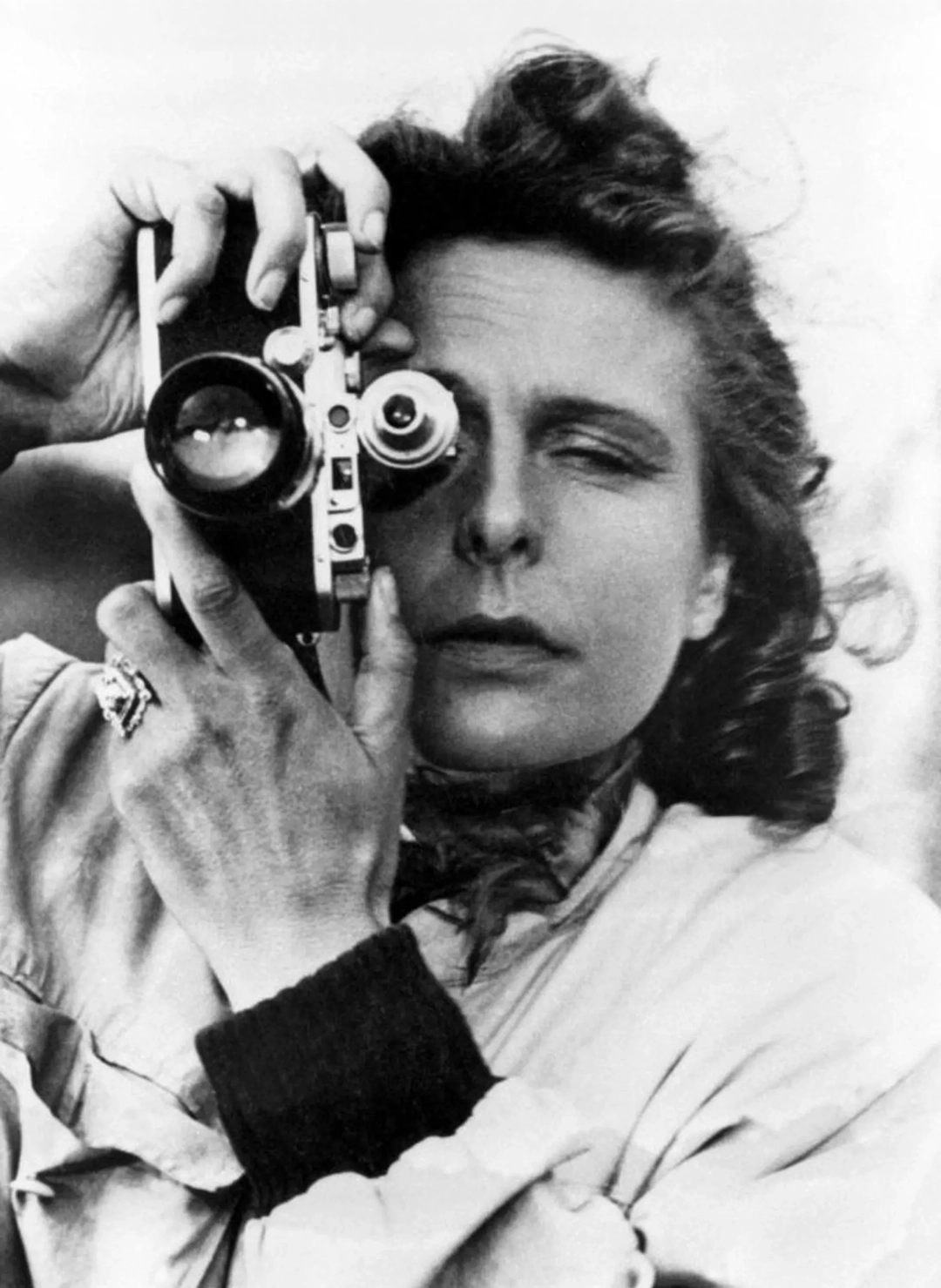

Riefenstahl at work on Tiefland in 1940

Leni Riefenstahl, German filmmaker celebrated for Triumph of the Will and Olympia, was a key figure in cinema in the 1930s. Her relationship with Hitler, whom she filmed at the Nuremberg Congress of 1934, marked her forever. Although she never joined the Nazi Party and was acquitted in two trials, her closeness to the regime turned her into a figure incapable of escaping the stigma. At that time, Hitler enjoyed a special magnetism for millions of Germans. He had reduced unemployment, restored the sense of dignity to a country humiliated by Versailles, and appealed to a collective sense of nation that promised to overcome recent defeats. Riefenstahl, like almost everyone, succumbed to that fascination. She herself confessed to having felt trembling and a “magnetic power” when hearing him for the first time.

Her film Triumph of the Will captured that popular devotion, merging the image of the leader with that of Germany. The rhetoric seemed to offer peace, unity, and personal perfection, although there were already signs of persecution against the Jews. Seen today, the film is a dangerous exaltation, but at the time it was celebrated even outside Germany. It was awarded in the France of the Popular Front and valued in the Soviet Union. After the Nazi defeat and the discovery of the Holocaust, the situation changed. Riefenstahl was interrogated and acquitted, but suspicion never disappeared. Wherever she went, she was remembered for her closeness to Hitler and was asked for explanations. She tried to rewrite her biography, denying metaphors or symbolic intentions in her films, although that effort stripped her own art of life.

In the persistent search for wood for the bonfire, the controversy is reborn today as incessant critical harassment. Documentaries such as that of Andrés Veiel insist on her proximity to Nazi power, raising accusations of having witnessed executions or worked with Roma children taken from concentration camps. Although some testimonies point in that direction, the evidence remains ambiguous and is not enough to dictate a definitive condemnation.

Leni Riefenstahl, 1935

Let us ask ourselves once more —as many times as necessary. How far does the responsibility of the artist go in horrific contexts? Should we evaluate the work for its aesthetic value or judge it for the ideology it served? Leni Riefenstahl —who can no longer expect even the peace that death grants— remains trapped between two irreconcilable forces. The formal greatness of her cinema, considered pioneering in audiovisual language, and the impossibility of separating her work from the political context that inspired it. Her long century of existence carried her from the admiration for her talent to the accusation of having sought shelter from the “sun of the moral world” in the icy shadow of the Deutscher Führer.

Comments powered by Talkyard.