Go to English Version

Go to English VersionIn 1992 I was very hungry. Not appetite—hunger. Cuba was enduring what was possibly the darkest year of what the government called the “Special Period in Time of Peace.” That was how President Fidel Castro named it in his televised addresses. For the weight of his words, for the absolute finality of every decision, he could be considered a pharaoh—and in some way, he was.

That same year, the Egyptian government officially announced the project to build a new Grand Museum, meant to relieve and update the aging Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square.

Wooden guardian statue of the Ka of the King wearing the Nemes headcloth. Image courtesy of IMG.

An Ancient and a Modern Egypt

Although the granite blocks inside the Great Pyramid of Khufu can weigh 60 or even 80 tons, most of them range between two and three. After placing the first, those tireless Egyptians laid the rest at a rate of about 315 blocks per day. Twenty years later, a well-dressed slave—singing praises to the funerary spirit of pharaonic industry—placed the final stone, high above all the others, on what became the pyramid’s tip. It still carries the weight of sixteen empty Empire State Buildings—or eight hundred thousand African elephants in the rainy season.

The first stone of the Grand Egyptian Museum was set in 2002. A rather light stone, in fact. A pebble. The next ones began to be placed five years later. At that pace, contemporary Egypt would take eleven and a half million years to finish even a modest pyramid—almost a sketch of one. Fortunately, they took matters into their own hands and urgently called an international design competition. Architects Róisín Heneghan and Shi-Fu Peng of Heneghan Peng Architects in Ireland won the commission.

Three years later, in 2005, the hammers began to strike—the dust, the noise. In 2010 came the transfer of the largest pieces, such as the colossal statue of Ramses II, and the mounting of the collections. Construction was declared complete in 2023. Thirty-one years of effort—with electricity, technology, cold water, air-conditioning, computers, and television. In that same span of time, mobile telephony evolved from the one-kilogram Motorola International 3200 to the 234-gram Samsung Galaxy S23 Ultra.

First Visitors

In October 2024 there was a partial—or trial—opening, to see how things were going. Only 4,000 visitors per day were admitted. On November 1 the museum was officially inaugurated with a state ceremony presided over by Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, attended by heads of state and European royal houses.

A few days ago, on November 4, coinciding with the anniversary of the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb, it fully opened its doors to the public.

Pragmatics

Official estimates place its cost around $1.2 billion, although some analysts—factoring in overruns and associated works—raise the figure above $3 billion.

But the Grand Egyptian Museum is astonishing. To express its scale in cold numbers does little to convey its proportions. The Louvre, for instance, is much larger in sheer exhibition space. The GEM is roughly the size of the Prado—or as if MoMA were devoted exclusively to Egyptian art. Counting the total surface area, the complex spans the equivalent of seventy European soccer fields.

Collection

The crown jewels of the collection are the Colossus of Ramses II and the Solar Boats of Khufu.

Ramses reigns over the grand entrance hall. The monumental statue, eleven meters high and weighing eighty-three tons, was moved with extraordinary care from Ramses Square in Cairo to its current setting in 2006—an engineering feat of breathtaking precision. Today the colossus stands as guardian of the museum and as a symbolic bridge between Egypt’s ancient grandeur and its modern architectural ambition.

The First Solar Boat of Khufu was discovered in 1954 by Egyptian archaeologist Kamal el-Mallakh, near the Great Pyramid. It lay in a sealed pit for more than 4,500 years—dismantled into over 1,200 pieces and reassembled over the course of a decade. Conceived to transport Pharaoh Khufu on his eternal voyage with the sun god Ra, it is considered the oldest and best-preserved wooden vessel in the world. It was transferred to the Grand Egyptian Museum in 2021 for permanent conservation.

A second boat was detected in 1987 through radar studies. Its recovery was overseen by Japanese archaeologist Sakuji Yoshimura, under the ever-watchful eye of Zahi Hawass. More fragmented and fragile than the first, composed of more than 1,700 pieces, it will eventually be displayed beside it within a publicly visible restoration lab.

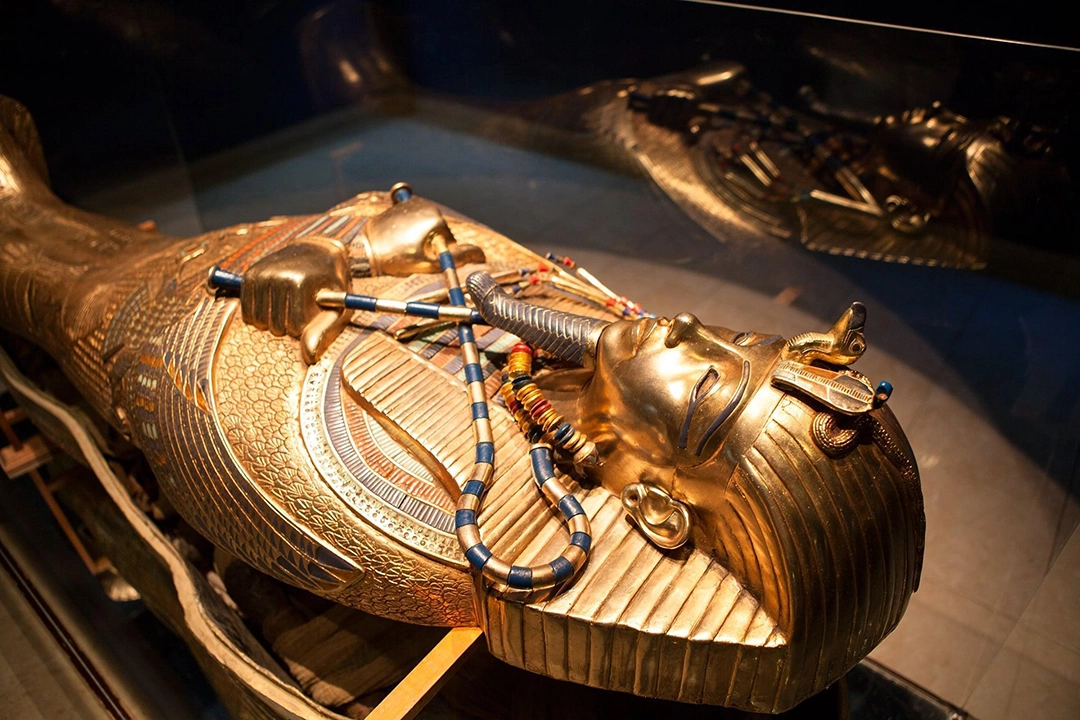

In all, the museum exhibits more than 100,000 objects from every period of ancient Egypt—from the Predynastic era to the Roman and Coptic. What fascinates me most is the complete collection of Tutankhamun’s funerary treasures—5,398 pieces—displayed in their entirety for the first time in a single museum and gallery.

The opening of the GEM has been received worldwide as a powerful cultural symbol—hailed by the press as “the largest institution in the world devoted to a single civilization.” Yet it also carries the weight of delay, unfinished sections, and the demanding task of offering a world-class museological experience.

And yet, unsurprisingly, I haven’t found a single article reading this vast historical and artistic display through an ideological lens—not the same, of course, but somehow akin to the way we question colonial monuments in the Americas: toppled or reinterpreted as symbols of subjugation.

From a certain—perhaps extreme—point of view, doesn’t this monumental narrative, beyond celebrating architectural greatness, also re-signify and glorify the legacy of a monarchy that fused political and religious power to its ultimate degree? The pharaohs were not merely kings; they were gods on earth. All the monumental art they produced was also, to a considerable extent, a pedagogy of power—a machinery for obedience and the perpetuation of memory. No other ideological system has endured so long, or with such absolute coherence.

Why does no one, even timidly or with a blush, seem willing to acknowledge—or even quietly ignore—the minimization of forced labor, the extreme mental and physical hierarchies, and the innumerable, now-forgotten forms of servitude that made these wonders possible? Why does the exaltation of a hereditary theocratic monarchy—one even more concentrated, sanctified, and absolute—outshine reflection on its human cost?

And what if we tried the mental exercise—purely as fiction—of dismantling this narrative, this entire architecture?

That will be a text for another day.

P.S. For the record, I find the ancient Egyptians extremely likable—all of them, not just the pharaohs.

Comments powered by Talkyard.