Portrait of Sheida Soleimani, 2025. Courtesy: Sheida Soleimani

Artist as Ghostwriter: Sheida Soleimani’s Tableaux of Care

The photographer and wildlife rehabilitator explores migration, exile and healing in her show at the International Center of Photography, New York

By Murtaza Vali in Profiles | 16 JUL 25 | Frieze Magazine

The last time I was at the CAC was in late 2017, for Caledonia Curry’s exhibition—better known as Swoon—titled The Canyon: 1999–2017. It was her first museum retrospective. I don’t recall every detail with clarity, but I do retain the certainty that it was a profoundly inspiring experience.

Eight years later I return to the CAC for the public opening of What a Revolutionary Must Know, by the Iranian American artist Sheida Soleimani (b. 1990, Indianapolis). It is her first solo museum exhibition in the United States, in which she presents many works from her Ghostwriter series.

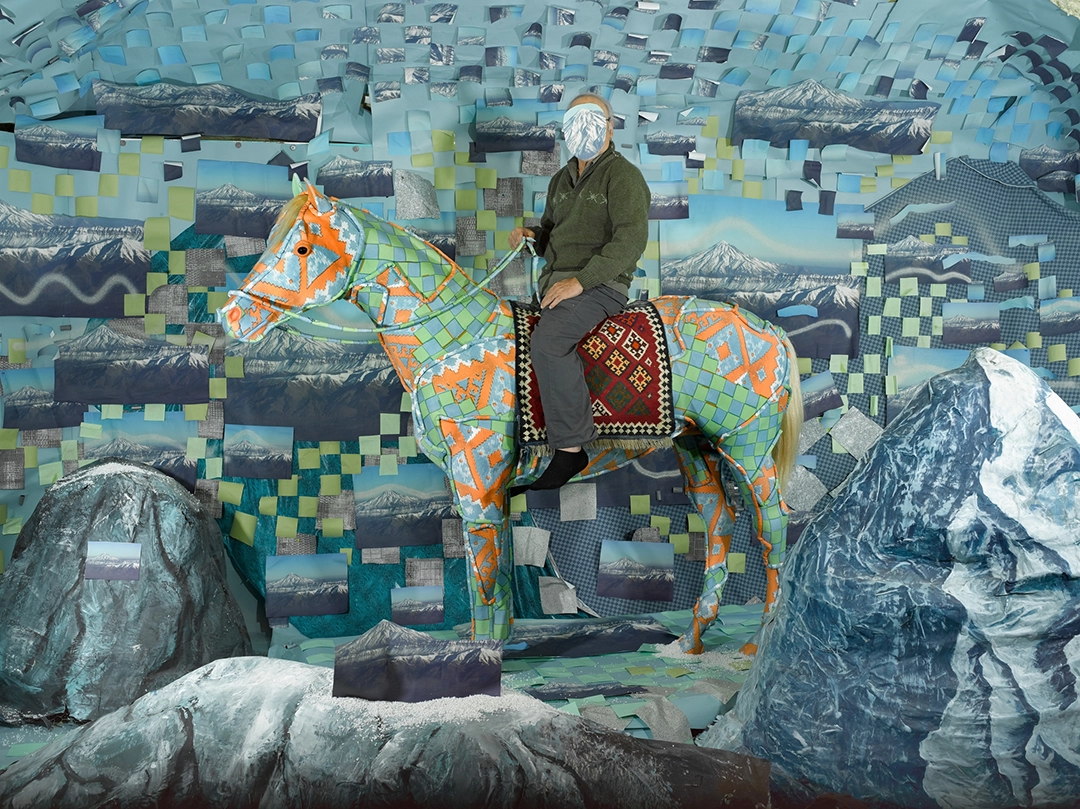

Deliverance, 2024, Archival pigment print, 72 x 90 inches. Image courtesy of the artist, Harlan Levey Projects, Brussels & Edel Assanti, London.

In it, Soleimani reconstructs her parents’ lived experience: their flight from Iran after the 1979 revolution, the passage that followed, their settlement in the United States, and the effort to sustain their ethical principles, their family history, and their sociocultural traditions.

The artist unfurls the narrative through a mise-en-scène where, in a surreal and gently theatrical atmosphere, objects, flowers, textiles and nature, animals and symbols coexist. Her family occupies the center in order to restage their most significant memories. We see them from behind or with their faces covered by paper masks. Possibly a practical—or symbolic—way to shield their identities, as if the risk of escaping a theocratic, authoritarian regime, and of a violent journey, had not been fully laid to rest.

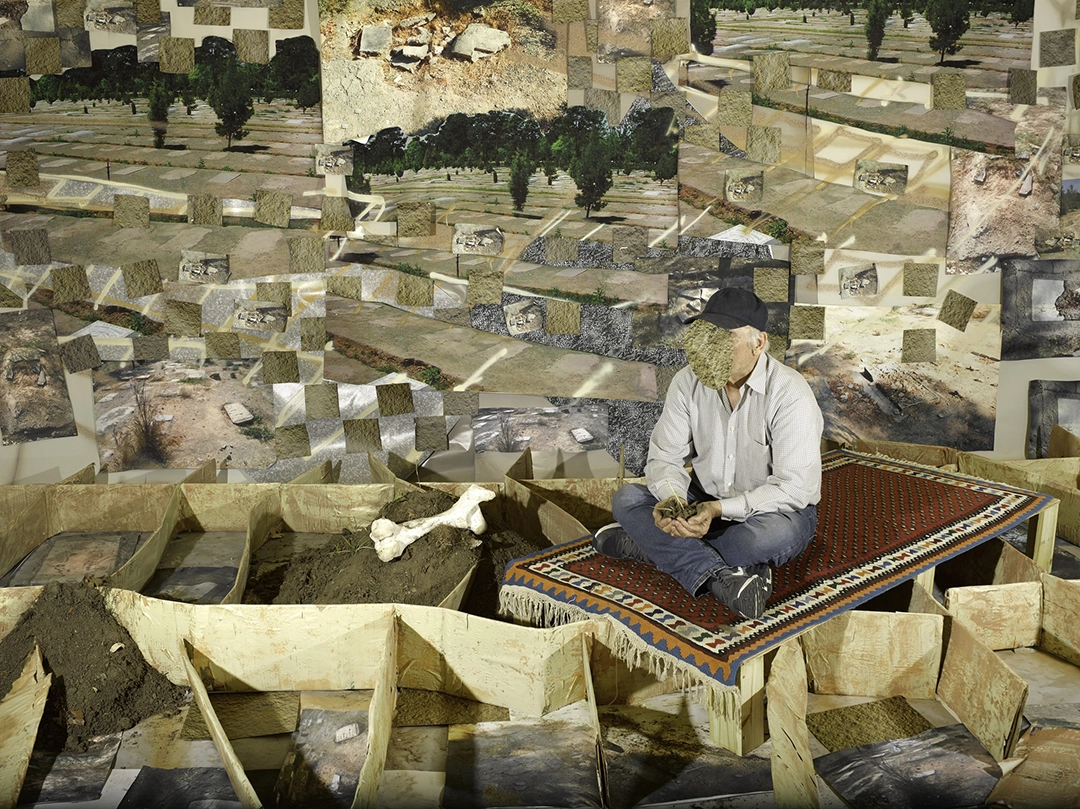

Behest Zahra, 2023, Archival pigment print, 44 x 60 inches. Image courtesy of the artist, Harlan Levey Projects, Brussels & Edel Assanti, London.

The series’ narrative thread, beyond the tale of persecution and refuge, weaves reflections on identity, memory, and political trauma. The photographs were not digitally manipulated. Soleimani seals her stagecraft with superimposed, fragmented images. A devoted piece of visual craftsmanship in which the accumulation of forms without semantic correlates produces a space that is unreal because it is illusory.

Two or three—perhaps more—organizing axes articulate complementary discourses that draw us nearer to or farther from the private and the communal. The arrangement of objects in the foreground is not performative, because the artist denies them movement. Both planes brim with memories of real experiences. Hence her photographs are not merely testimonial records: they are tableaux of dialogue. The lens ceases to be a device of mastery and capture—as Soleimani herself notes when invoking photography’s colonial history—and becomes a collaborator; it subverts the traditional visual hierarchy. Every element appears on the same plane, coming into focus with similar prominence, in a democratic gesture of representation.

The symbols in her imaginary derive as much from Persian tradition as from her own biography. In her talk she shared several allegories. One, of striking beauty: the decapitated lamb and the sugar cube. It evokes a ritual of sacrifice. Her mother told her that when lambs were sacrificed, a sugar cube was placed in their mouths to calm them before the cut. Just as she later perceives the revolutionary dynamic in Iran’s history: sweetness before violence, hope and repression. In turn, the flying carpet points back to a childhood marked by Orientalist stereotypes, which she resignifies with irony through her political memory. Her father, a persecuted physician, crossed the mountains on horseback to flee Iranian repression, wrapped in a sweater that still appears in some of her works.

Panacea, 2024, Archival pigment print, 60 x 44 inches. Image courtesy of the artist, Harlan Levey Projects, Brussels & Edel Assanti, London.

We see how the artist integrates the resources of contemporary visual culture as a means of intensifying her critique. The chromatic excesses, the pink or gold backdrops, the strident contrasts: they attract the viewer only to confront them with another story of violence, censorship, and exile. She argues that the viewer must first be seduced in order to be forced to look at what is unpleasant. Sugar and lambs? It is worth reflecting on how a significant portion of the visuality of the so-called “Third World” reaches us overflowing with chromatic density, with a glut of signifiers that, by sheer excess, becomes monotone. Might this be a response to a long-sustained scarcity, to the deterioration of the social ecosystem, to the darkness of corruption?

What A Revolutionary Must Know, 2022, Archival pigment print, 40 x 30 inches. Image courtesy of the artist, Harlan Levey Projects, Brussels & Edel Assanti, London.

Another aspect to consider in Soleimani’s practice is the constant appearance of the animal as a mirror of the human. Not only in the work. Her project Congress of the Birds (a clinic for wild birds that she personally runs) rescues and rehabilitates thousands of animals injured by architectural infrastructures and human negligence. Can we read the fragility of birds as another emblem of precarity? Is caring for those that crash against glass a metaphor for rehabilitation? Possibly, in her imaginary, it is equivalent to repairing the fracture generated by the violence of state power. That crossing between art and direct action expands her language beyond the museum, toward a terrain where aesthetics and ethics become one.

Truce, 2024, Archival pigment print, 18 x 24 inches. Image courtesy of the artist, Harlan Levey Projects, Brussels & Edel Assanti, London.

Other animals recur in her work: the snake, for example, appears in Stellar Cues (2025) and Affinity (2024). In both, the mother holds the dry skin that once contained a living snake. This translucent exuvia, which retains the pattern of scales, seems rigid enough to be held upright and “challenged.” The most threatening thing is its shadow, somehow being addressed. We also see scorpions—vinegarroons, to be precise. They are not the scorpions they appear to be: they have neither stinger nor venom, yet they keep their pedipalps, those equally threatening fore-claws. Much can be read in the symbolism of this bestiary threaded through so many scenes. I also perceive its polysemy and, precisely because of it, I understand the whole less. I prefer to hold to the analogy between the aerial and the earthbound, between good and evil, between spirit and matter—wherever it takes us.

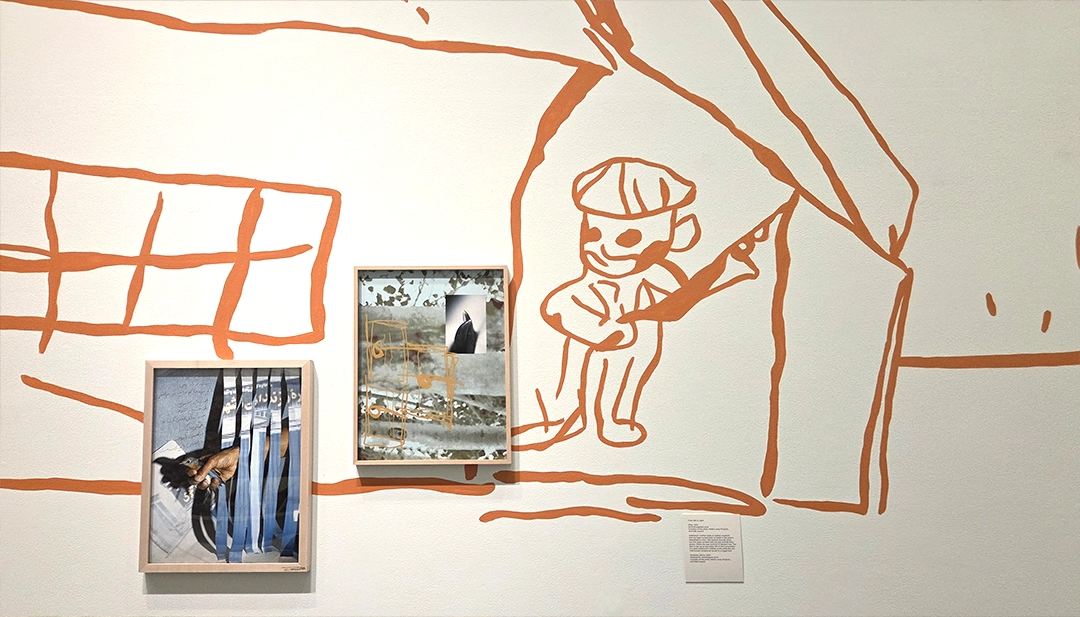

Agitator, 2023. Archival pigment print. Courtesy of the artist and Edel Assanti and Harlan Levey Projects, Brussels.

Dissident, 2023. Archival pigment print. Courtesy of the artist and Edel Assanti and Harlan Levey Projects, Brussels.

Color in her work is likewise a propositional language. Vibrant patterns and saturated surfaces build a hypnotic space that converses with Pop aesthetics. When political figures appear as soft sculptures that deflate, the symbols of power are turned into carnival props. In counterpoint, images of martyrs and the disappeared challenge a gaze accustomed to normalizing suffering through the brutality that saturates the media.

At the conceptual root, the stories of her mother— a nurse who cared for animals at home after being unable to practice in the United States— and of her father— a physician persecuted for his political convictions in Iran— become universal metaphors of resistance and conservation. Soleimani turns family memory into a visual archive of struggle, in which the personal becomes collective. She interlaces—physically and conceptually—tenderness with the terrible aggression and the violence demanded by survival. Not as a linear chronicle, but as a multicolored mosaic where beauty, death, ice, and needles compose a visual body that rearranges our perception of pain and healing. In the end there remains the savor of a small victory, of prevalence. During her talk I saw her parents, seated modestly at the back of the auditorium—the quietest protagonists in the world. An enchanting image; for me, the most moving of the entire exhibition.

Finally, we find—posted in areas of emphatic visual relevance—references to the game Snakes and Ladders. Born in ancient India as Moksha Patam, here it is much more than a pastime: it is a parable of the family’s journey and destiny. Its ladders, metaphors of virtues that lift; its snakes, emblems of vices that drag one toward the abyss—together they turn the board into a spiritual map where every ascent and fall embodies karma. True, in the West the game has shed its moral ballast in favor of a more inconsequential chance, but in this context—and perhaps in its birthplace—the universal image persists: life as a passage between unexpected ascents and inevitable descents, a sway of fortune and loss that reflects the fragility of existence.

Beyond a museography that generated a measure of friction for me—a secondary, monochrome visual discourse linking each piece in a somewhat dissonant root system—I found it a judicious selection, seductive enough to mobilize the reflective mechanisms of a sensitive viewer. Very Persian at heart, What a Revolutionary Must Know is a symbolic chessboard raised from elements of considerable emotional weight. If one attends closely and holds the semantic rhythm of each work, the viewer ends up reformulating one of the questions Soleimani lays upon the table: how can we avoid the normalization of pain through the incessant, insensitive repetition of the news media?

Sheida Soleimani

The artist and educator Sheida Soleimani (Indianapolis, 1990) lives and works in Providence, RI. She is an Associate Professor of Art at Brandeis University, and her practice probes the intersections of art and activism through photography, sculpture, collage, and video, with particular attention to genealogies of violence, migration, and political memory in Iran and its diaspora. She trained at the University of Cincinnati (BFA, 2012) and the Cranbrook Academy of Art (MFA, 2015). Recent solo exhibitions include Panjereh at the International Center of Photography (ICP), New York (2025); What a Revolutionary Must Know at the Contemporary Arts Center (CAC), Cincinnati (2025); and no breath, no breeze at the ICA at MECA&D, Portland, Maine (2024). Her series Ghostwriter—the core of her work in recent years—has entered the V&A Photography Collection at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum.

In addition to her academic and studio work, Soleimani is a federally and state-licensed wildlife rehabilitator and the founder/Executive Director of Congress of the Birds, Rhode Island’s only rehabilitation center dedicated exclusively to birds, where she integrates clinical care with a visual discourse that frames care as a cultural practice. Her work has been the subject of critical profiles and international coverage (Frieze, FT Weekend, WVXU), as well as institutional projects underscoring how her constructed tableaux re-situate archival and press imagery to examine the relation between power, the body, and political iconography.

Comments powered by Talkyard.