The Bertholdi Columbus statue, gifted to the City of Providence in 1893, was removed from Columbus Square on Friday, June 12, 2020, following the recommendation of the Special Committee for Commemorative Works. Long contested for the legacy of violence and exploitation attributed to Christopher Columbus, the monument remains in storage, well preserved, as its appraisal and the eventual use of any proceeds from its potential sale are determined.

Each year, before or after the contentious celebration of October 12, impassioned debates erupt across Spanish‑speaking America over its legitimacy. In Spain it is the National Day, as well as the Día de la Hispanidad. Throughout this continent it is marked as Día de la Raza in countries such as Mexico and Argentina, though often with an approach that rejects Spanish roots and centers instead on the exaltation of Indigenous peoples. In the United States it is celebrated as Columbus Day—an ideal occasion for acts of dissent.

The outcry against the evangelization of the Americas began to gather force in the mid‑20th century, fueled by decolonization movements that emerged in the wake of World War II. With independence still fresh, many former colonies hurried to rethink and rewrite their history from a new perspective. Although the Patria Grande had been formally emancipated for over half a century, the sudden agitation stirred intellectual elites, who seized the moment to draw the attention of the public—and, inevitably, of political elites.

In the United States, amid the just struggle for civil rights in the 1960s, the average intellectual—whether idle or opportunistic—went beyond his rejoicing at the entry of the oppressed into all economic and social strata and began feverishly compiling tales of genocide and displacement attributed to a “demonic” Spain.

By 1992—just after those Olympic Games in Barcelona immortalized by the voices of Freddie Mercury and Montserrat Caballé—celebrations of the 500th anniversary of the so‑called discovery of the Americas raised a dust storm that has yet to settle. While many states marked the occasion as the “Encounter of Two Worlds,” others reframed it entirely. In 2002 Hugo Chávez proclaimed it the Day of Indigenous Resistance; Evo Morales also sang the rights of original peoples. Eurocentric narratives yielded to postcolonial studies, focusing on the violence, exploitation, and endurance of those communities.

With the rise of social media and the influx of millions of hyper‑sensitive commentators, the din has grown deafening. Each October now brings a fresh wave of arguments, most of them reheated echoes of that lethargic lament—legitimate in many respects, yet often amplifying the old Black Legend spread by the Anglo‑Saxon world in the twilight of the Renaissance.

It is undeniable that colonization led to the mass genocide of Indigenous populations. Millions died through war, through diseases brought by Europeans—smallpox foremost among them—and through the inhuman conditions of slavery and exploitation. Yet the prevailing discourse often insists on seeing this date solely as a glorification of suffering and the destruction of entire civilizations: Aztec, Inca, Taíno, and others.

This year, overnight, many of the world’s leading newspapers echoed a murky piece of news that, to this day, no one can confirm: that Columbus was not Genoese but Spanish, and moreover a converso Jew.

Anglophone headlines—unsurprisingly—declared as fact that Columbus was neither Italian nor Christian. The furor began with the documentary Colón ADN, aired only days ago on Spanish Television.

Colón ADN: Su verdadero origen is a documentary produced by RTVE, Story Producciones, and the University of Granada. It proposes nothing less than to rewrite world history by exploring, through genetic studies, the true lineage of Christopher Columbus. Narrated by Cristóbal Colón de Carvajal, a direct descendant of the navigator, the film interweaves scientific research and historical narrative to cast new light on the enigmatic origins of the so‑called discoverer of the Americas, confronting myths, traditions, and revealing data.

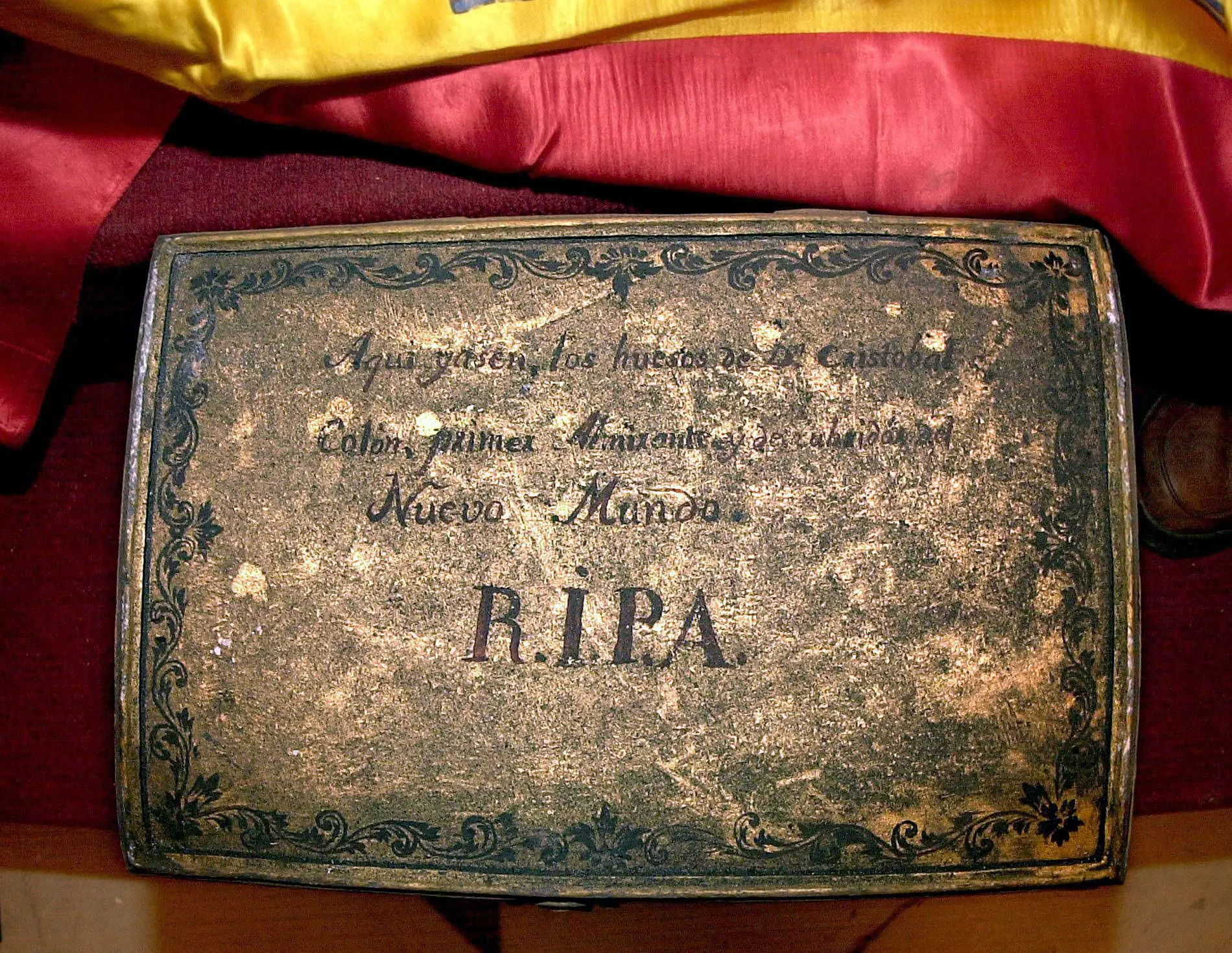

The film claims that the navigator came from a family of weavers in southern Spain and that he never ate acorn‑fed ham. Specialists remain skeptical, sensing more media spectacle than serious inquiry. The remains in question have been under the custody of a single man—the forensic scientist José Antonio Lorente—since 2003. No one else has had access. Lorente has published no analysis in the twenty years since the exhumation. There is not a single verifiable piece of evidence. Yet the film’s director, Regis Francisco López, declares that after these revelations history “must be rewritten.” Media platforms rushed to amplify the story.

The scientific community, however, remains unmoved. When the sealed urn was opened, it did not contain a mummified admiral clutching an identity card, but 150 grams of bone dust and a few fragments, the largest only four centimeters long. For perspective, a tin of sardines holds roughly 100 to 120 grams. Moreover, the remains included those believed to be his brother Diego’s and his son Fernando’s.

What, then, is the point of all this commotion? Where is it meant to lead? One can understand that the forensic scientist, the filmmaker, and the producer might have their reasons. Less obvious is why the story reverberated so loudly across the global press. I found it in The Guardian, The Times, The Washington Post, The New York Times, El Nuevo Herald—and of course throughout the Spanish media. So much ink for an unverified hypothesis? Was he or was he not a Christian? And if he was a Jew, what fragment of history truly needs to be rewritten? It is not as though Christmas would suddenly be moved to December 27—though Nicolás Maduro did, indeed, move it up to October 1.

Perhaps the uproar has subtler causes. Perhaps it is fueled by the enduring Black Legend that England and the Low Countries have propagated since the sixteenth century—a narrative that has never abated, perhaps unremarkable now from sheer repetition, but still perpetuated by an inertia few bother to counter. Or perhaps the world is simply bored—no club football, an audience weary of missile smoke. It is worth pondering, for international breaks can be exhausting, even Tartine Bakery’s bread can grow tiresome. And on the other hand, could it be that the see‑saw of Hispanidad is indeed so deeply lodged at the other extreme?

Forensic scientist José Antonio Lorente, in an image provided by the production company of the documentary 'Columbus DNA.'

Comments powered by Talkyard.