The photograph was taken by Evelyn Sosa in Havana on December 31, 2017, at the New Year’s Eve party organized by HAPE Collective. HAPE Collective is an international platform born in Havana in 2016 with the mission of promoting cultural exchange through boundary‑breaking musical encounters. Made up of DJs, musicians, and cultural promoters from different countries, the collective has created a unique space for collaboration and experimentation, connecting local music scenes with global networks.

The Party

Last week, at the exhibition Osy Milián opened at Galería Zapata, I told Evelyn Sosa I wanted to write about one of her photographs. I also told her that it would not be an interpretation or a critical assessment of her work, but rather of that particular image. And I did not say then—though I say it now—that if the result resembled what is known in the field as an “art review,” it would be incidental and by no means intentional. That said, above you can see the photograph in question: one that draws my attention more than any of the others I’ve kept. For many reasons, but above all for one that seems essential to me: I know well, and hold deep affection for, the one I believe to be its central figure.

Aside from Evelyn’s presence, there are three forces vying, with differing intensities, for that fleeting instant the camera rescues from oblivion: the setting and the two young women who inhabit it. The presumed night is the starting point of the narrative—the space where minor gestures build meaning. In this night, as in any other, there is something unsaid yet sensed. The feeling of being on the edge, on the threshold where one world ends and another begins. My first reading is a soft warning: there is a line you cannot cross.

The harsh light, so easily taken for granted by any who perceive it, seems to grasp what interests the photographer and takes sides. The frame does not deceive either. I’ve left an annotated copy to show you the image’s axis of rotation. Its texture is as rough as those nights that have yet to find direction. Everything is contrast. The suspended moment does not seem to seek an answer—rather, it leaves us with many questions. To begin with.

Who are they?

Two girls who feel safe enough not to be forced into any pose or attitude. It all stems from a small, fragile intimacy. One drinks. The other watches.

The one who drinks. What is she telling us?

Her sip is not of thirst, but of gesture—one older than this and every other party. To hide part of the face, yet holding with a sidelong glance—barely focused—an air of detachment or sensory overload. She seems to literally overlook the boldness of whoever dares to turn her into evidence. And, surrendered to the gesture, she drinks without urgency, without theatrics, as she has done countless times before. She wears a garment that glimmers in motion, its tiny incandescences alive with their own will, intent on drawing or deflecting attention, as the moment demands.

The suspended bottle transcends mere consumption: it is a declaration of identity and at once an act of self‑protection. When we drink in public, in a social context, we mark distance and trace subtle borders between the private and the collective. In social psychology this is known as heightened self‑awareness under public scrutiny. When someone feels observed or exposed, they respond with automatisms of collective use: they light a cigarette, raise a drink to their lips, yawn—gestures at once ambiguous and, in some way, defensive.

Identity is also a veil. In the Western tradition the face is the emblem of truth; to hide it is to elude confrontation. There is something deliberately withdrawn in her posture. That expected movement of lifting the bottle acquires, on another level, a certain philosophical weight: it is a simple act—an evasion, a digression, an attempt to draw attention to itself—yet also a way to slow down time, to dilute consciousness. As Kierkegaard would say, perhaps she drinks to “postpone the burden of being.” A statement, after all, that not everything human is visible in the apparent, and that her interiority must remain beyond the reach of “practically” everyone else.

The other girl, the one who watches. She…

seems to hold the ontological plane of the scene. She looks at Evelyn—she looks at us—and her mere presence embodies the notion of the witness. She is the “Other” Emmanuel Levinas speaks of, the one who calls us to respond. A gaze that cannot be reduced. Her very presence obliges us to acknowledge her humanity and to act ethically. Yet notice—she is not accusatory. She does not seem to demand a response. She is, for now, simply the reminder that the “Other” is watching.

This manner of looking, so difficult to describe, is pure Presence. Evelyn intuits who she is. I am not so sure she truly knows. And that is true of many people. But she does not intervene. She watches, steady, dense, silent. And that guardian‑angel vigilance confirms: I am with you. She is friend and mirror. She manifests a tacit complicity. Between those dark eyes and the viewfinder, an emotional bond is forged that needs no words, no gesture, no sign: I am the being who… For that reason I have no doubt: it is a gaze of approval, of support, and also of protection.

In friendships—especially between women—there is a keen ability to communicate through almost imperceptible gestures. Posture, gaze, or silence are enough. Those eyes do not simply look at the camera; in fact, they do not look at it—they pierce through it. They are fixed on the photographer, on Evelyn, and it is possible they sense she might feel tense under the first girl’s wariness. She takes on a protective role, perhaps even a maternal one, revealing even a faint trace of pride.

Because Ilse has always been a vigilant accomplice, because she has perhaps spent too much time in that sharp intersection between shadow and desire. From that rearguard she transmits a calm watchfulness over her friend’s creative act. I like to believe—because it is a beautiful thought—that when Evelyn perceives how much humanity and emotion live in Ilse’s gaze, she shifts her focus and decides to safeguard what, in that moment, feels like refuge.

This photograph—and every other I have seen by Evelyn Sosa—is not conceived to be enjoyed, judged, or understood through the male gaze. Woman is at the center of all her work. Not just any woman, far from it, but those who carry the essential quality Evelyn needs to collect in order to make her testimony visible. It is a body of work that, distilled in this single image, defends the right to silence, to exhaustion, to rest, and above all, to ambiguity. For Evelyn’s women inhabit the edge of time, the edge of desire; they burn in black and white.

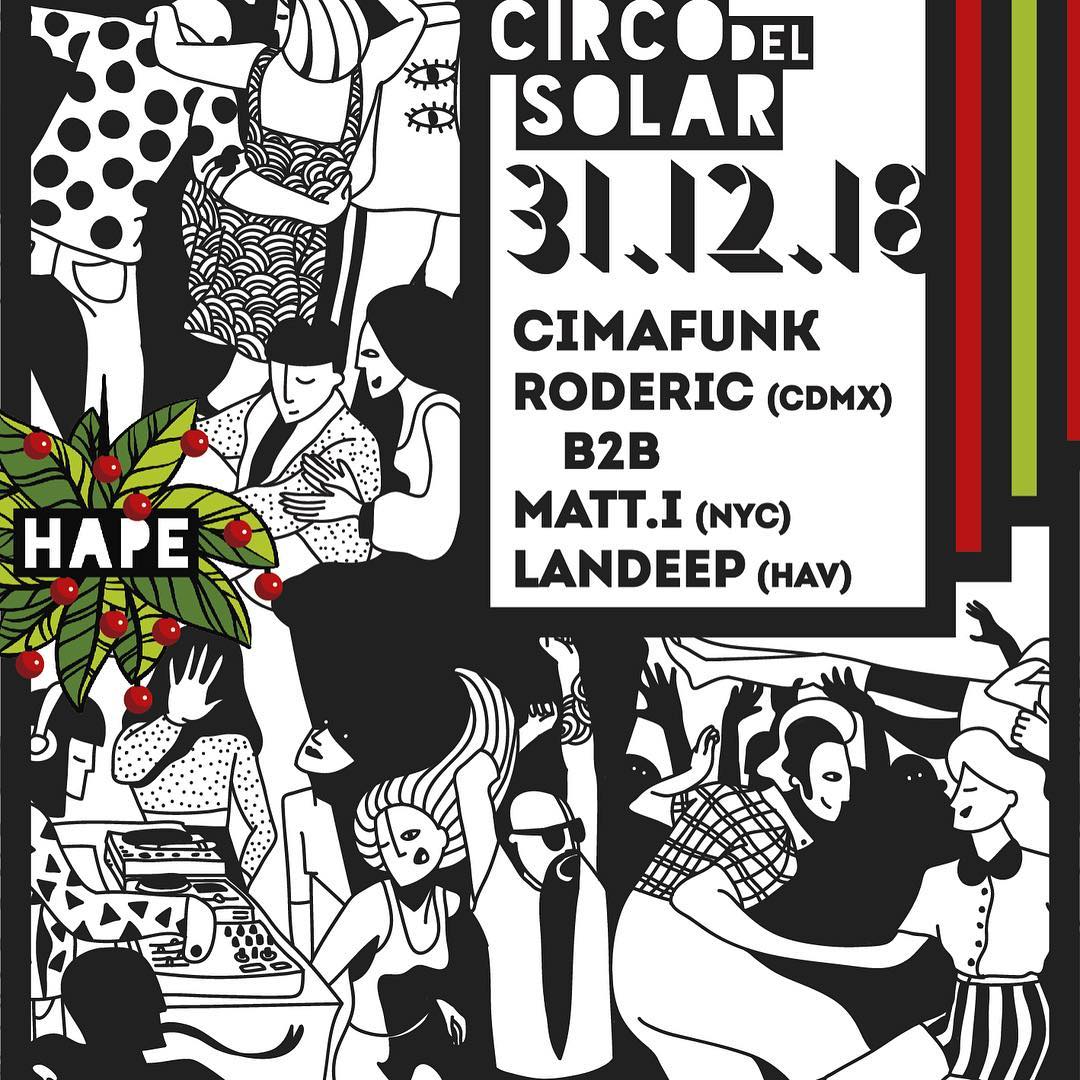

HAPE New Year from Havana, where we celebrated the arrival of 2019 at Circo de Solar organized by @copperbridge in collaboration with @hapecollective & @vedadosocialclub feat: @cimafunk @ciaomatti @ro.deric @djlandeep art: @amaiasarah

Comments powered by Talkyard.