The Sleeping Gypsy (1897), oil on canvas, 129.5 × 200.7 cm. Henri Rousseau. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired in 1939 through funds donated by Simon Guggenheim expressly for its purchase. Accession no. 1939.467. Formerly in French and American private collections, the painting is regarded as a pivotal work in defining Rousseau’s late period and the early contours of modern art.

Philately was one of the small devotions of my childhood. I inherited hundreds of stamps from my father. I could never say whether he collected them himself or simply bought them for my brother and me. Among all of them, one in particular held my gaze with disproportionate insistence: a reproduction of The Sleeping Gypsy, the 1897 painting by Henri Rousseau that I finally saw years later at the MoMA.

Scrutinizing that tiny image was one of the most intense and enduring visual experiences of my early life—perhaps the first that awakened my desire to interpret what I saw. A woman asleep in the desert, her mandolin and water jar beside her, while a lion approaches, almost timidly, to breathe her in under a swollen moon. An icon of dream imagery in art, and one of Rousseau’s most celebrated works.

Rousseau replaces the narrative logic of the scene with a dialogue between symbolic elements of a shared, almost primordial nature. The woman’s deep sleep, which would normally suggest absolute vulnerability, does not, in this case, consign her to helplessness. Perhaps what truly sleeps is her habitual vigilance—her native state of alertness. In the background, the unconscious—those internal traumas not yet shelved in the archives of forgetting—takes the form of a lion, watching from the periphery, acutely alert. Although traditionally a symbol of power and threat, here it appears arrested in a gesture stripped of violence, reinforcing the sense that it may be the woman’s psychic shadow observing the momentary softening of her own identity.

This occurs in the desert—an a-historical space with no cultural coordinates. An archetypal plane in which signs operate in their purest state. The moon asserts its own agency as witness, orchestrator of this subversion of conduct, presiding over the improbable coexistence of danger and calm, animality and humanity, sleep and vigilance.

I doubt Rousseau sought anything more than to show—without attempting to resolve it—the coexistence of contradictory forces within a singular soul, or to meditate on the dark territory where the deformed flowers of the interior life take root. That realm where rationality abdicates, and from which an ancient, ambiguous, revelatory consciousness rises.

He is, without question, one of the artists who shaped my vocation for the visual. Fifty-five of his paintings are currently on view at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia. The exhibition is titled A Painter’s Secret, and—as with any exhibition of his—it is rare, magical, and filled with drifting enchantments.

The curators say they sought to dispel the myth of Rousseau as an ingenuous painter. They see him instead as a kind of visionary who understood the seductive power of calculated awkwardness, of pictorial candor as a strategy. His almost childlike frontal compositions and rigid figures operate as masks—concealing a far deeper understanding of the human psyche while presenting only a primitive, seemingly innocent figuration. From that supposed naïveté he forged an imaginary world with virtually no limits. In his paintings, echoes of folk art and pre-Renaissance Christian iconography mingle with what critics have called the “magic and frank spontaneity of children’s art.”

A Carnival Evening (1885–1886), oil on canvas, 117.4 × 89.6 cm. Henri Rousseau. First exhibited at the 1886 Salon des Indépendants. Now in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Acc. no. 1963-181-64, acquired through the 1963 bequest of Louis E. Stern. Long considered one of Rousseau’s early masterpieces, the painting already displays the deliberate flatness, nocturnal atmosphere, and liminal sensibility that would shape his mature style.

One of the works on view, Carnival Evening (1886), is considered among his most enigmatic. Two costumed figures walk arm in arm as they leave a shadowed forest. It is a premonition of what surrealism would later embrace—strange, and at the same time, romantic.

In his lifetime no one understood the symbolism of his work; he was ridiculed as a technically limited painter. For decades he was dismissed as a clumsy autodidact from whom little could be expected—someone who painted this way because he couldn’t paint otherwise.

Today, critics are beginning to suspect that the naïve ones were everyone else. That Rousseau understood perfectly well the advantages his manner of painting could afford him in an art market undergoing rapid transformation. In late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Paris, the notion of the “primitive,” the “popular,” or the “childlike” became increasingly aligned with authenticity, purity, and originality—values the avant-garde held in the highest regard. To be seen as a “pure” creator, uncorrupted by academic training, heightened the fascination his work elicited among artists, collectors, and critics alike. His unfinished, planar, and subtly off-center aesthetic—those compositions arrested in a time without a clock—began to satisfy the hunger for authenticity that modernity installed as one of its founding myths.

A Painter’s Secret remains on view until February 22.

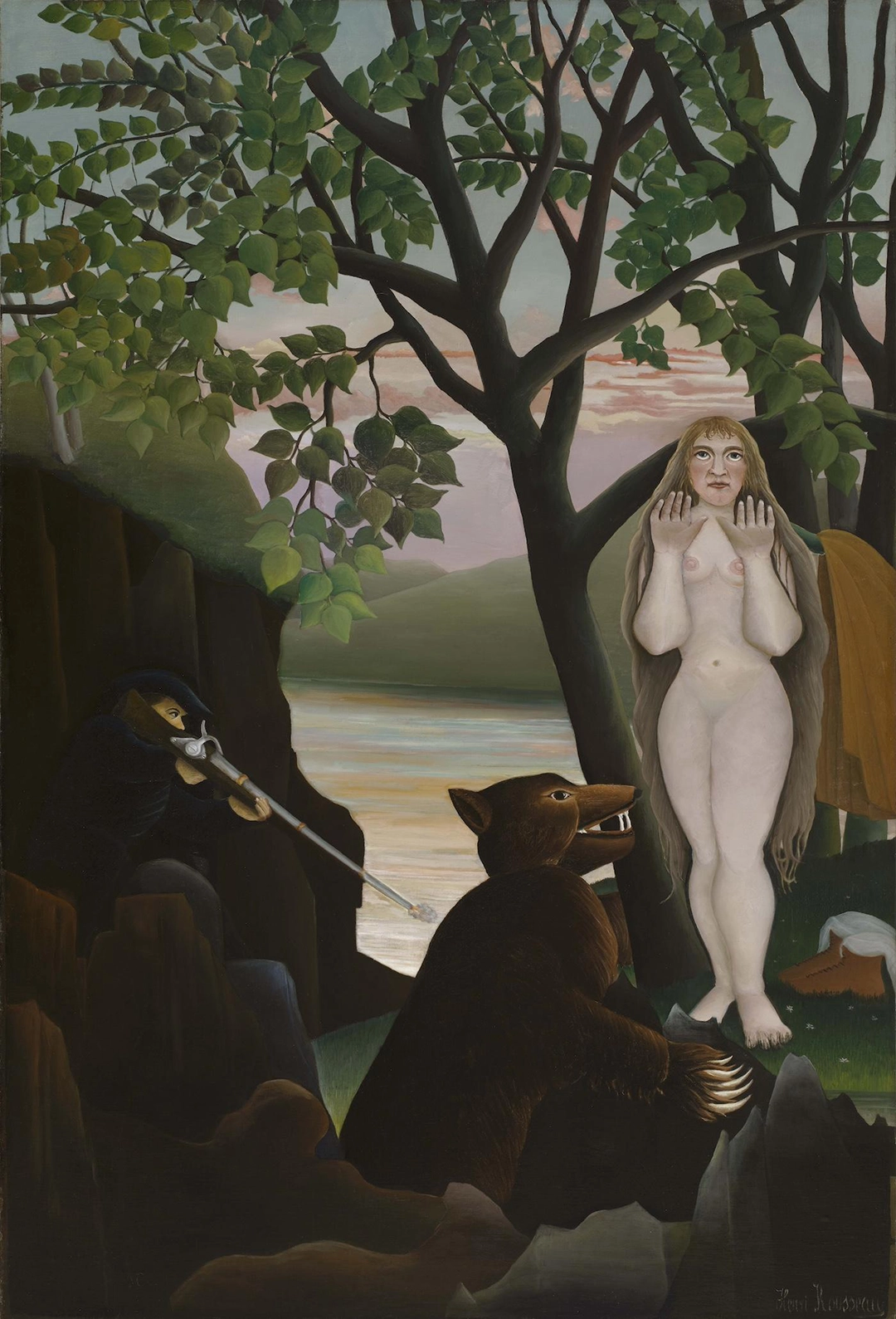

Unpleasant Surprise (1899–1901), oil on canvas, 157.5 × 98.1 cm. Henri Rousseau. The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia. Formerly in European private collections prior to its acquisition by Albert C. Barnes. A seminal example of Rousseau’s late style, marked by ritualized composition, a heightened sense of theatricality, and the meticulously constructed artifice that defines his mature pictorial language.

Comments powered by Talkyard.