Go to English Version

Go to English VersionHuman genius can be observed in many of its works. Nowhere is it more detectable than in the arts: music, literature, and the visual arts. As a species, seen from above, we are all fairly clever. But some are—or were—truly exceptional. What did they require to rise above the rest? What made them singular, beyond the reasoning most of us share?

The everyday Homo sapiens possesses two fundamental tools to navigate an ecosystem of extreme competition and produce outcomes—bad, good, and occasionally, extraordinary. These are them: a highly developed brain, capable of anticipating a Tuesday after a Monday, and the hands. Together, they are responsible for producing all the works that fill us with legitimate pride and that we display, more than anything, as evidence of our sophistication, of the sensitivity that overwhelms us, and of how well our talent detector functions. Only rarely—Stephen Hawking being one exception, and a few others—a mind within an immobile or ungoverned body has managed to produce brilliant results.

Brain and hands evolved almost simultaneously. Each propelled the other forward, and the development of one depended profoundly on the other.

It would be simple to rest on the notion that the evolution of our brain gave us language. Yet the skills required to produce finely crafted stone tools, and to carry out other complex behaviors—such as burying the dead—long predate verbal communication. Many of these activities cannot be learned through observation alone and require some degree of explicit instruction. It is therefore plausible that the need to transmit or share them forced the invention of new forms of communication.

Evidence suggests that hominins were teaching one another skills through direct and deliberate explanation as early as 600,000 years ago, before the emergence of our species, without spoken language being involved. Gestures may have sufficed. In keeping with this, certain cave paintings in France depict hands missing fingers, which may represent—beyond the imprudence of placing one’s hand inside the jaws of a hyena—a primitive form of sign language.

Paco de Lucía

In a colossal leap forward to our own time, we must acknowledge that the fingering of Paco de Lucía, for example, cannot be understood merely as speed or mechanical dexterity. It is a phenomenon of neuromuscular precision refined to an almost inconceivable degree. Each finger of his left hand exerted the exact pressure required to materialize each note. Minimal, and at the same time absolute. They operated as autonomous entities subordinated to a superior architecture of control that, beyond any ordinary human faculty, I insist on calling genius.

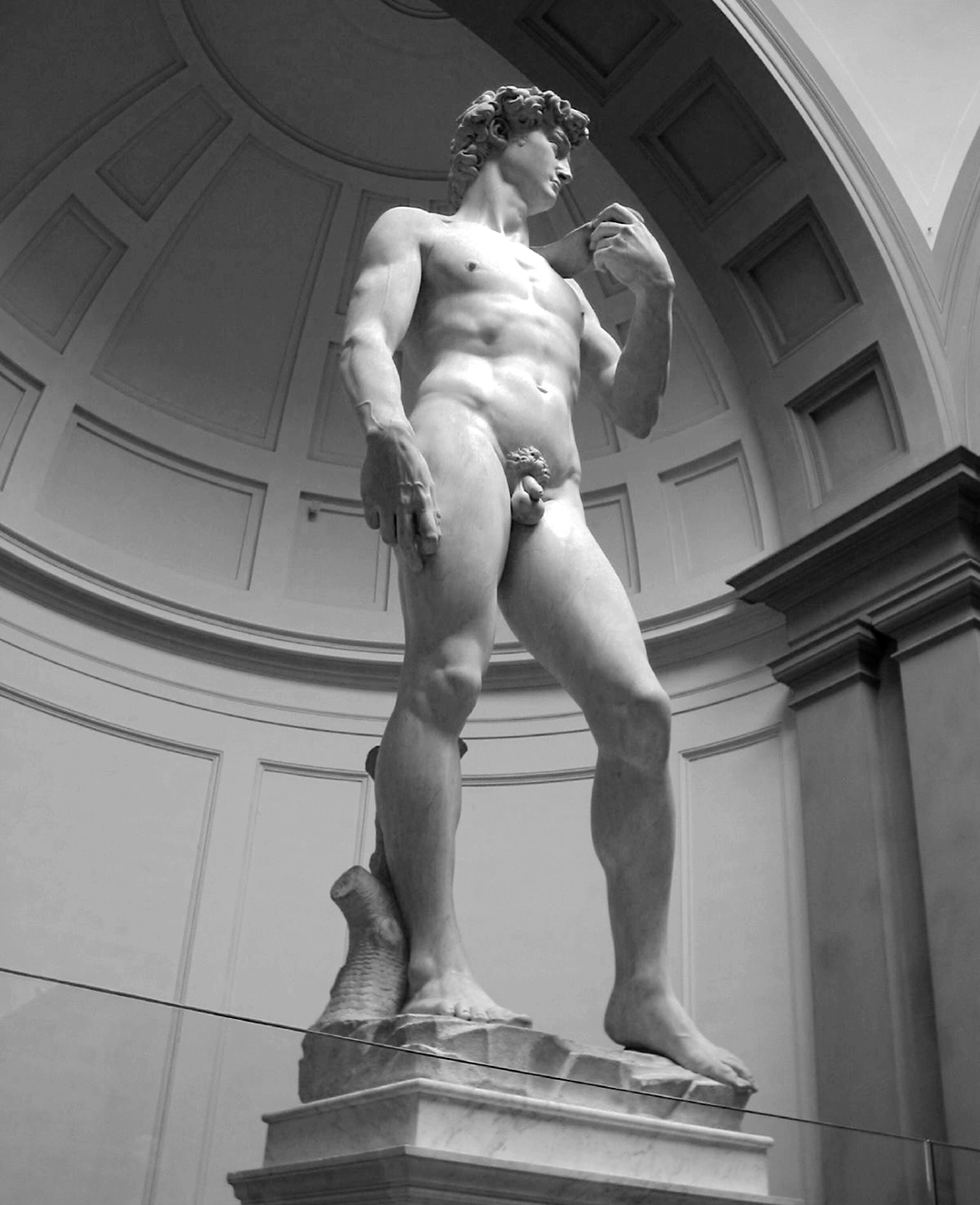

It was also the extraordinary neocortex of Michelangelo Buonarroti—the outer layer that includes the regions controlling motor function—that allowed his prodigious hands to sculpt, among other things, the sublime right hand of his David.

Both cases allow us to glimpse that singular wiring between a brilliant brain and hands of exceptional operational precision.

I want to pause for a moment on the right hand of the biblical hero, one of the most observed, discussed, and interpreted elements of the sculpture. Only to revisit why so many have spoken of it.

Since the sixteenth century, it has been one of the fundamental symbolic and psychological centers of the work. Giorgio Vasari, the first great historian of modern art and a contemporary of Michelangelo himself, perceived that in this sculpture nothing obeyed naturalistic fidelity, but rather a higher logic of meaning. It is, in fact, disproportionately large in relation to the rest of the body. Many believe this was a deliberate decision responding both to optical and expressive reasons.

The sculpture was originally intended to be seen from below, placed at height, and Michelangelo corrected perspective by enlarging those parts of the body that needed to retain their visual force at a distance. But beyond this technical correction, its enlargement responds to a symbolic hierarchy. It is an instrument of will.

Its fingers are neither tense nor relaxed. The tendons are visible beneath the marble’s surface, and the veins, carved with a precision unseen since the time of Greece, transmit vitality—life awakened, circulation, and above all, a rare form of containment.

Károly (Charles) von Tolnai, the Hungarian-born American scholar and one of the greatest Michelangelo specialists of the twentieth century, observed that the artist chose to represent the moment immediately preceding combat. One of waiting, which—of course—can be mapped and reproduced across the entirety of its frozen gestural field. The sculpture waits, but the myth burst forth the moment the dust was cleared. It reinterprets the traditional meaning of this champion of faith. It moves us away from triumph and martial prowess and places before us a subject conscious of his dense spirituality. Like an instant surrendered to history, it suspends movement and leaves, within the concentrated hand, the totality of his emotional energy.

Kenneth Clark, in his celebrated study of the nude, likewise stated that David does not represent physical strength itself, but the strength of consciousness—that his right hand is the instrument of his intelligence, not of violence. Nothing brutal. Simply precise, overwhelming if we intuit how it gathers energy, refining the blow. It has also been interpreted as a form of anticipation: it has not yet acted, but the eruption will be inevitable. Modern historiography further observes that its size seems to belong to a more mature body than that of the youth himself. This subtle discordance introduces a temporal dimension. It appears to announce the hero David is not yet, but is on the verge of becoming. A sculptural form that contains a promise. This is hardly surprising, given that Michelangelo, profoundly influenced by Florentine Neoplatonism, conceived the body not merely as matter, but as the manifestation of an interior reality. The hand, in this sense, is the exteriorization of an invisible decision.

From a technical standpoint, it constitutes an extraordinary demonstration of Michelangelo’s command over marble. The transitions between surfaces, the articulation of the knuckles, the differential tension of each finger, and the variable depth of the veins create the illusion of a living organism beneath petrified skin.

It is unnecessary to convince anyone that the hand—and the sculpture as a whole—is genius, produced not only by a prodigious mind, but by a celestial mastery of the hands that executed it. Whoever is not convinced—do not insist—consider them lost.

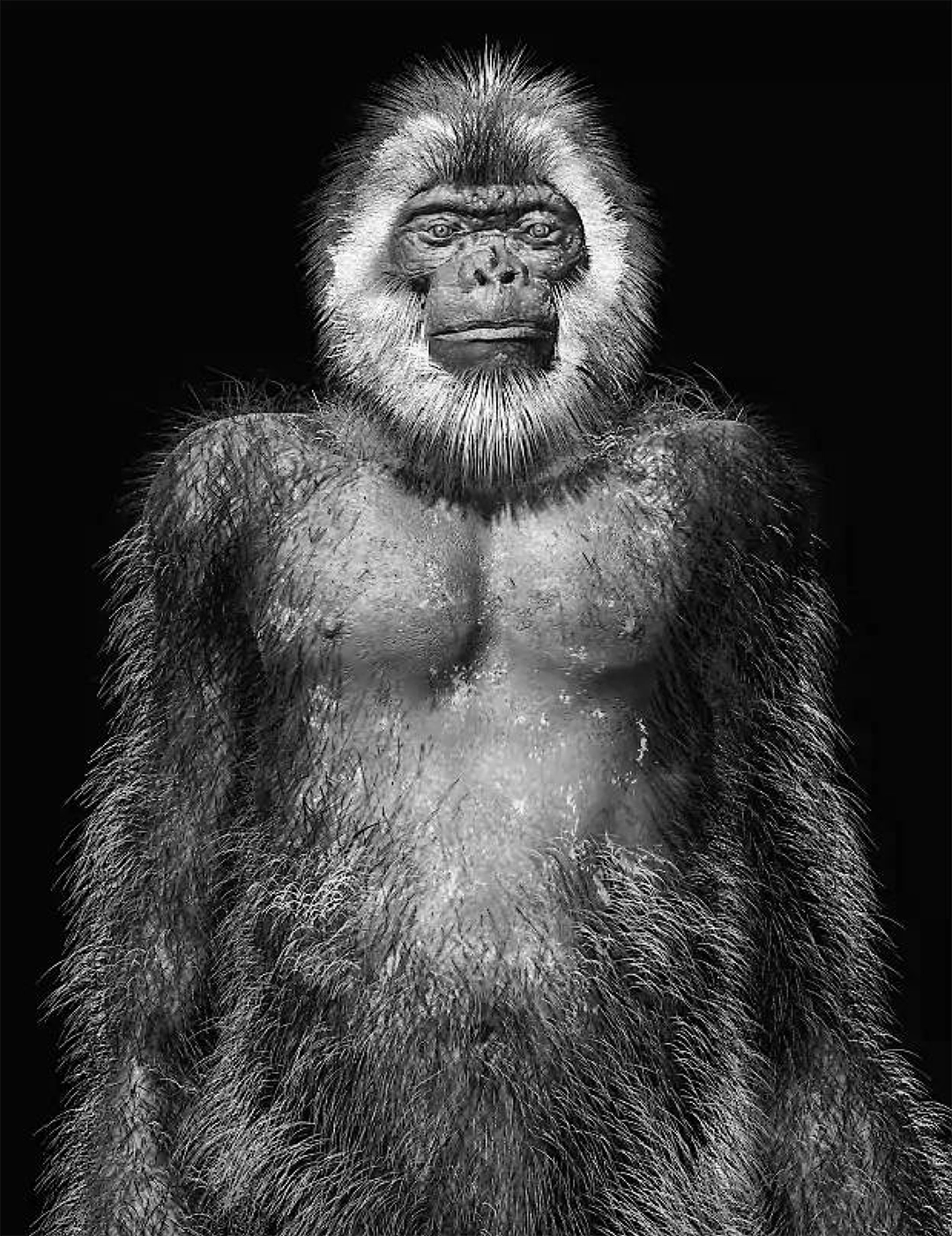

Ardipithecus. John Bavaro Fine Arts Science Photo Library

Let us now step back several million years. A hominin we have called Australopithecus began to take things somewhat more seriously and intuited that swinging from branches would lead nowhere. It chose instead to wander upright, and its hands began to change substantially. They had already begun to do so in the earlier Ardipithecus.

Later, in the common ancestor of Paranthropus and Homo, some 3.5 million years ago, the fingers became less curved, the thumb grew stronger, and the wrist acquired greater mobility. This allowed for the versatile use of tools. With the earliest Homo, the consumption of meat and the production of more complex stone implements increased evolutionary pressure on the hand. They favored increasing dexterity. At the same time, the brain took notice and expanded as well, especially in the areas that govern its movement.

Walking upright, consuming more meat, using the hands as a visor to scan for predators, and making obscene gestures at neighbors—digitus impudicus and other ancestral signals of contempt—began to shape that natural marvel we call the modern human hand. Today, sapiens still walk among us who use their hands like australopithecines and stand upright while secretly longing to return to all fours or climb back into the trees, from which height they bark down at us for no purpose other than to extract a fragment of human attention.

Michelangeli pauci, Australopitheci multi.

Comments powered by Talkyard.