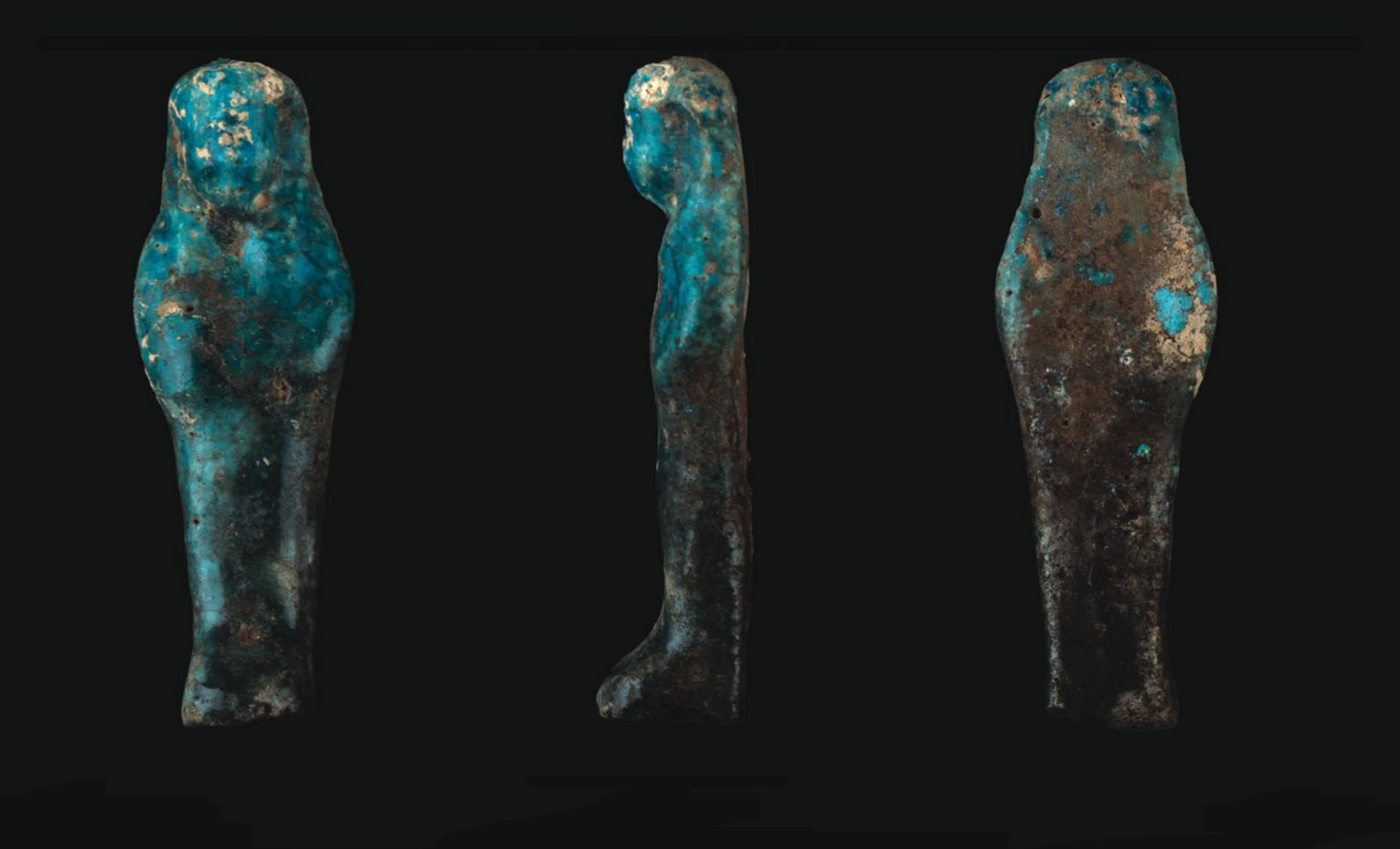

Photograph accompanying the article, “The vast collection of ancient Egyptian artefacts held by University College London’s Petrie Museum includes hundreds of shabti.” The Times, February 16, 2026.

The Petrie Museum of Egyptian and Sudanese Archaeology, part of University College London (UCL), houses one of the most important collections of Egyptian artefacts in the world. It preserves more than 80,000 objects recovered from excavations conducted between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Among them are hundreds of shabti, small funerary figures that formed part of the ritual equipment of tombs in ancient Egypt. These objects—some more than 3,000 years old—constitute an invaluable source for the study of Egyptian funerary beliefs and practices.

Made primarily of faience, stone, wood, or terracotta, shabti typically took the form of mummiform figures and, in some cases, bore agricultural tools. Their number varied according to the social rank of the deceased, reaching into the hundreds in high-status burials. The presence of these pieces in the Petrie Museum is the result of archaeological campaigns led by the Egyptologist Flinders Petrie, whose excavations contributed decisively to the development of modern Egyptology

'Shabti' de Seniu. Tebas, principios de la dinastía XVIII (hacia 1525-1504 a. J c.). Metropolitan Museum of Art (nº 19.3.206), Nueva York. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

These shabti were placed beside the prominent dead with the symbolic purpose of performing, in death, the manual labor that had been carried out on their behalf in life. According to Egyptian religion, the deceased could be summoned to undertake agricultural work in the afterlife, and these figures would answer in their place. Many bear inscriptions derived from the Book of the Dead, declaring their willingness to work voluntarily in the name of the deceased. It is a remarkably explicit expression of a structured conception of labor and of a rigid hierarchy that survived even death itself.

One must look not only at the beliefs these affluent Egyptians held about their gods, but at their brazen inclination toward idleness. Convinced that a second existence awaited them beyond the threshold, they had the audacity to commission effigies of those who had served them in life, so that they might continue to do so after death. For these unfortunate beings, labor did not end with mortality. Perhaps for this reason, the religions that would later emerge promised something more appealing—a kind of paradise where one needed only to choose a suitable place in which to drift in the shade.

Comments powered by Talkyard.