Go to English Version

Go to English VersionWatching the American Alex Honnold perched on the skyscraper tower in Taipei—508 meters high—immediately carried me to the image of King Kong. With one difference: the latter has an intellectual author, the filmmaker Merian C. Cooper, who directed the original 1933 film alongside Ernest B. Schoedsack for RKO Radio Pictures. The design and animation of the iconic gorilla (stop-motion) were carried out by Willis O’Brien, considered the pioneer—or at least one of the pioneers—of the language. The original screenplay was developed by Edgar Wallace and James A. Creelman. A love of heights runs through these lives and these acts of creation. Merian C. Cooper, besides being director, producer, and screenwriter, was an aviator and an officer of the Polish and American air forces, respectively. By contrast, Alex’s father, Charles Honnold, originally from Germany, a community-college professor, lived with autism spectrum disorder in a body marked by overweight. He died of a heart attack at fifty-five, still young. His mother is originally from Poland, and held the same occupation as the man who became her husband.

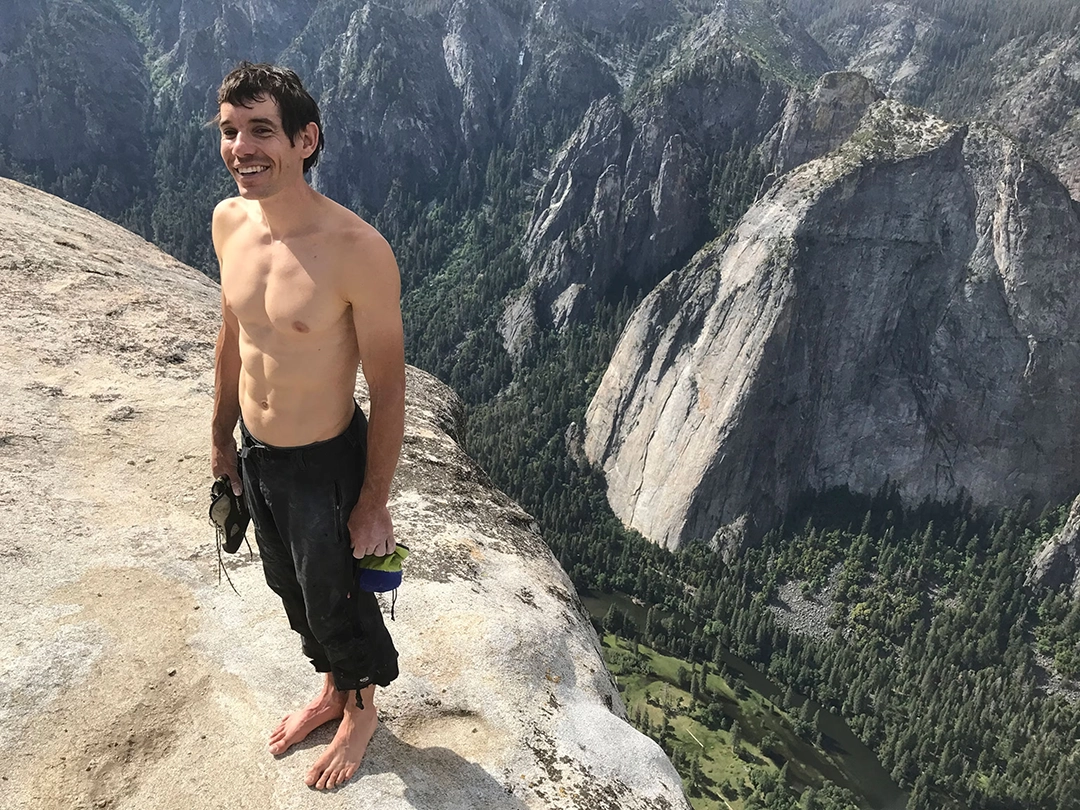

If we take into account that Honnold has, to his credit, the ascent of Mount Watkins, The Nose, and the northwest face of Half Dome, among some of his “heroic” feats, we are looking at a primate with very good odds of soon having devoted followers. I say “primate” because the man enters these rites without ropes. Hence the resemblance to the celebrated ape. If the vitality of your daring contradicts the reasoning that preserves life, what is desired is not precisely to live, but perhaps to survive—filling an emotional and affective void.

What did King Kong represent in its time? The monstrosity and savage character of the figure were associated with the way modernity—with its triumphal parade of progress (tall skyscrapers, streets policed and guarded, swift mobility, accelerated economic growth, among other factors)—was separating us from our vital axis (nature, physical contact, a calmer life, lower percentages of conditions, or diseases, associated with neurodevelopment), in order to turn us into alienated individuals whose function is to remain operative within a context of absolute capitalization of global resources.

We live under legal and juridical frameworks in which violations of elementary human rights are increasingly frequent; government policies that guarantee citizens’ security are absent; and human relationships become ever more liquid. King Kong condenses resistance to that industrialist advance that would flatten any sign of difference, spontaneity, authentic connection to the natural environment. So, what does Honnold represent within this sociological equation that summons the famous character back to mind? He would be the ape’s opposite flank: a man who chooses death every day because he learned to survive in a home where his father—with autism—could not care for him as he would have wished. What option remained? To choose to die every day under the veiled, sensationalist idea that the death is worth it—the exposure of climbing more than 500 meters with no rope—because, as life is treated like Russian roulette, if one has the luck to overcome all these “summits” (summits of what?) one probably obtains the attention he did not receive in childhood and adolescence—above all, in the first of these stages.

At some point Aristotle is said to have remarked: “Give me a child until the age of seven and I will show you the man.” Do we have, on these peaks, a mature forty-year-old man—or a child who never had the chance to have a father capable of loving him as he deserved? How did Dierdre Wolownick, Honnold’s mother, carry these family breaches? It would be useful to investigate, though most likely it was an intimidating weight. In some way, that five-year-old child from Sacramento—who began his first ascents in gymnastics—was trying to dematerialize that burden borne by both parents, to make it lighter.

In the end, as the old song says: “to climb to heaven you need a big ladder and a little one.” Honnold would never arrive—through a career, research, art, or any ordinary occupation—at the “big ladder,” which is to say fame, recognition; so he chose to hide the “little ladder,” which we associate with humility, the search for essence, knowing ourselves to be small, because he did not manage his ineffable solitude through a reunion with himself.

Another aberrant aspect of the news media is that they have circulated the claim that Honnold’s amygdala does not display the activity it should in situations where humans feel fear. Supposedly the gambler of death is not prey to fear when he decides to undertake these adventures. And they repeat it—indiscriminately—as though a family, and a human being who has chosen to vanish, to become incorporeal before supreme designs, had no right to be admitted into physiological normality—and into the condition of autism his father lived with. To sell, one must sell by marking a genetic difference that turns our Sacramento gorilla into a humanoid. That makes him susceptible to yet another achievement that would have to be attributed to a white American man—one whose image can be used in global spectacles of high-risk events, to produce branded documentary content, environmental-awareness campaigns (“turn into an ape, don’t pollute, please”). Meanwhile, King Kong would wonder why his roars—which, to make matters worse, were part of the first soundtrack used in a film—today resemble a global cry, unresolved in any healthy way, more than a true spirit of resistance.

Guayakil [sic], January 30, 2026

Comments powered by Talkyard.