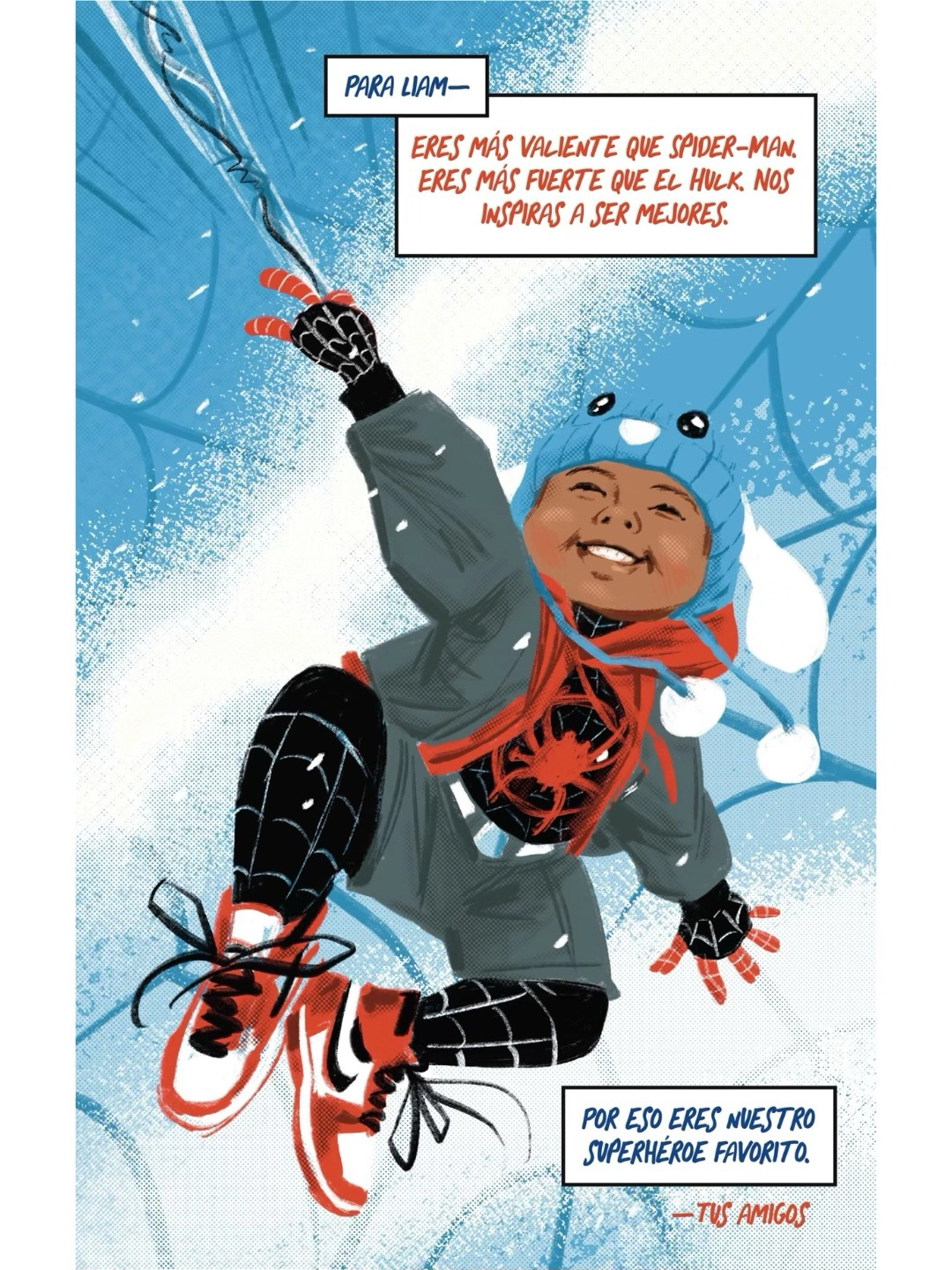

Liam Conejo Ramos in Minneapolis on January 20.

Ali Daniels (AP)

We have previously discussed how a photograph — or an image — can rearticulate the public perception of reality. How it can encapsulate experience, much like a verb does, rendering it transferable, exposable, and legible in a specific way.

Any story is a continuum, difficult to apprehend in its full extension and multidimensionality. In order to be understood and fixed as experience — and as argument — it must be reformulated through its most expressive qualities. This is why we say — often, if not always — that an image is worth more than a thousand words.

The strongest images shelter singular, emotional moments. They frame them, make them readable — that is, they turn them into objects available for rapid interpretation. Through their symbolic power, they distill reality of its scattered and diffuse nuances, making it, so to speak, portable. When a discrete event is absorbed into mass consumption, it loses its singular condition and begins to function as argument, as graphic evidence sustaining broader claims.

Ed Wexler, You Are the Worst of the Worst, editorial cartoon, digital illustration, ca. 2023, © Cagle Cartoons / cagle.com

As John Berger reminds us, every image is a re-created vision, detached from its original time and place. This applies even to photography, which we often mistake for a neutral record. As noted earlier, once it circulates, the photograph ceases to be the instant it crystallized. It becomes a fragment of reality with the capacity to reconfigure that reality itself.

Liam Conejo Ramos is a small Ecuadorian child, wearing a bunny hat, carrying a delicate backpack — the most tender and innocuous figure one might imagine. Yet within a photograph, he becomes a powerful resource, even a dangerous one, depending on who is judging it. His benign fragility reveals, by contrast, the implacable and hermetic hardness of the officers of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

The immediate grammar of the image allows us to read a basic antagonism between vulnerability and power, between childhood and the State, between home and capture. The press reported that Ka Vang, a columnist for the Star Tribune, lost her breath upon seeing it; it produced an almost physical impact as its first effect. While I do not believe in hyperventilated reactions, I understand this one.

What becomes most interesting is the second phase — once the image has been converted into a symbol — when it turns into a fundamental ingredient of the stories and narratives that begin to circulate. It leaves anecdote behind and consolidates itself as an autonomous statement, bypassing testimony in order to emblematize the administration of fear, brutality, and the erosion of principles we once assumed to be foundational.

As Susan Sontag would explain, photography, insofar as it “provides evidence,” becomes a political instrument by transforming what is debatable into something that, for a moment, appears proven. The image functions as testimony before it functions as explanation.

In semiological terms, an image operates on two planes. On the one hand, what Roland Barthes called the studium: the shared cultural field that allows us to read the situation — uniforms, the gesture of custody, the urban setting, the child as passive subject. On the other, the punctum: the splinter that protrudes, wounds, and breaks free from the code. It is the intimate kick of the sign. The blue hat — almost harmless, almost tender — is capable of opening a semantic wound that, precisely by contrast, demonizes the encounter and renders the confrontation intolerable.

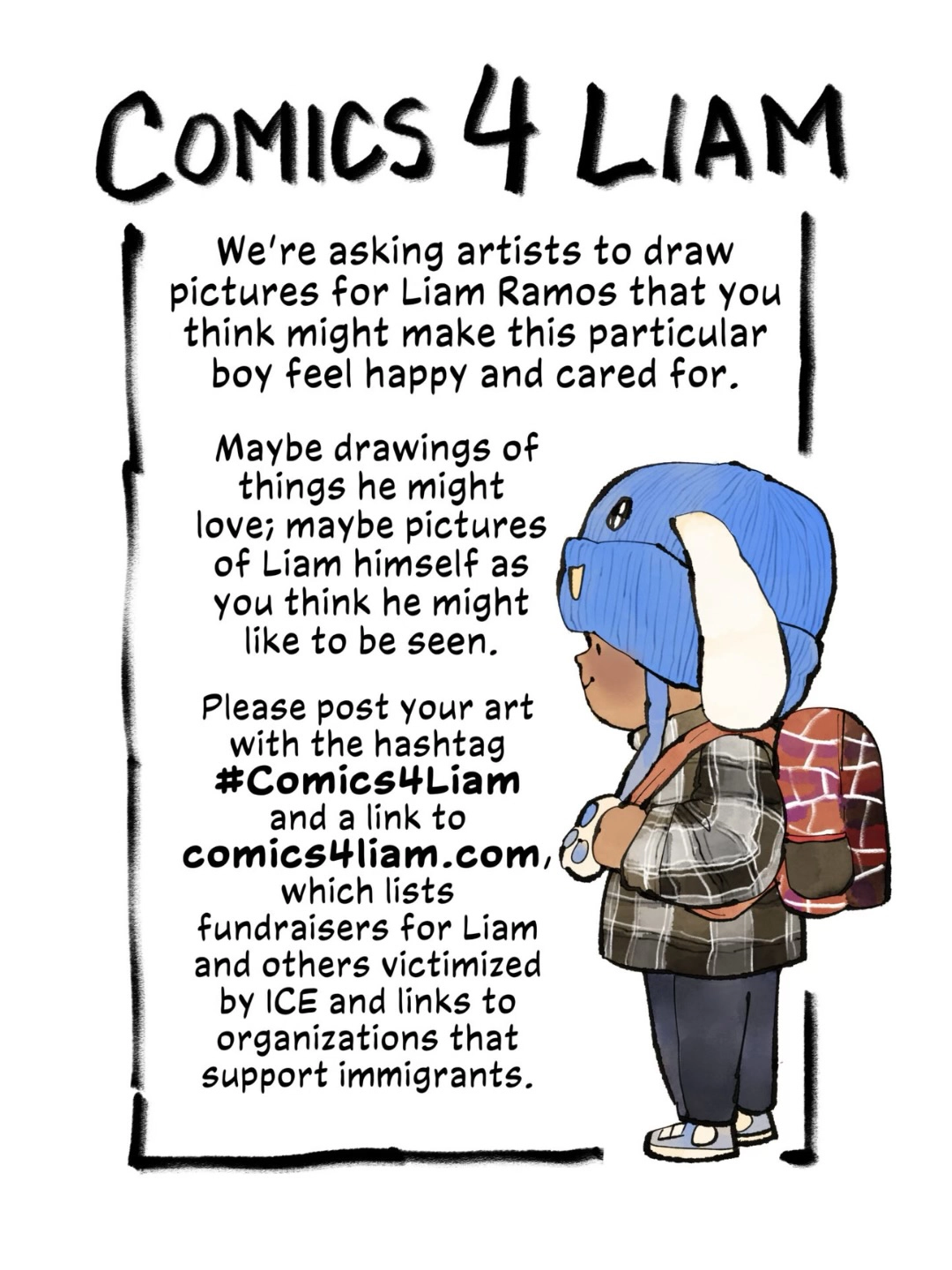

Image taken from the profile of kusi.art

From this point on, the debate over competing versions (who said what, who denied what) becomes secondary in the analysis of the image. Mentioning it is not idle, however, because even briefly it reveals the struggle over the assignment of meaning.

Authorities from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security offered an explanation intended to rest on “security” and “procedure.” Witnesses, those present at the scene, and family members denounced coercive, leonine, and illegitimate tactics. The judge — absent from the scene but holding the image in hand — ultimately issued a harsh critique of the manner in which the detention was carried out and ordered the unconditional release of the child and his father. The contradiction matters as symptom. The image’s force, born of the brutal contrast between the child’s rampant innocence and the brute force of a handful of adults, compels all parties to abandon ambiguity and stake their ground in the struggle to control the narrative.

We enter a fourth level. Image and reading, in vertiginous circulation, begin to summon other stories. Photography as a site where moral tensions are inscribed. One recalls the famous Napalm Girl (The Terror of War), another image that exceeded the event and became a global symbol, with all the ethical complications that entailed — exposure, trauma, political appropriation, the dissemination of an image without the victim’s consent. That same photograph is now debated once again, in terms of its status in the digital era — suspended between historical memory and moderation policies — and even over questions of authorship and credit.

An “iconic” image is never a sign exhausted by a first reading.

As a conclusion, we can say that the photograph of the child Liam functions as a body of water in which the historical tensions between art and politics begin to tremble. Photography fixes aesthetics as a form of persuasion and politics as choreography. It redefines reality, rendering it legible, debatable, shareable, and contestable.

Its visceral power, in my view, lies in the fact that it places the automatic moral immunity of childhood in crisis. It probes, clumsily but relentlessly, into the core of human experience, at the point where the preservation of the species is activated. The protection of the young is central in the world of higher vertebrates, in the domain of the living. It is what must not be touched. And yet, at this moment in history, there are individuals — specimens — who not only violate that primordial instinct, anterior even to consciousness, but allow themselves to be caught by a photograph.

Liam may be the beginning of the end, or the end of an era. It depends on us. I hope.

Comments powered by Talkyard.