Image taken from Ana de Armas’s Instagram. It was posted on November 30, 2024. Hours later, Mario Pentón — multimedia journalist for Martí Noticias — also commented on his personal Instagram account: While millions of Cubans struggle to feed their children, Manuel Anido, the stepson of (…) Canel, spends more than 12,000 euros studying in Spain.

I open X (formerly Twitter) the way one steps into a Roman coliseum—looking for blood. It is the perfect arena in which to insult one’s neighbor, the one you will hate as much as yourself. X knows my obsessions: Real Madrid, Shih Tzus, and a good meal. It also knows—though I’ve never marked it as an interest—that I sometimes linger over posts about Cuba.

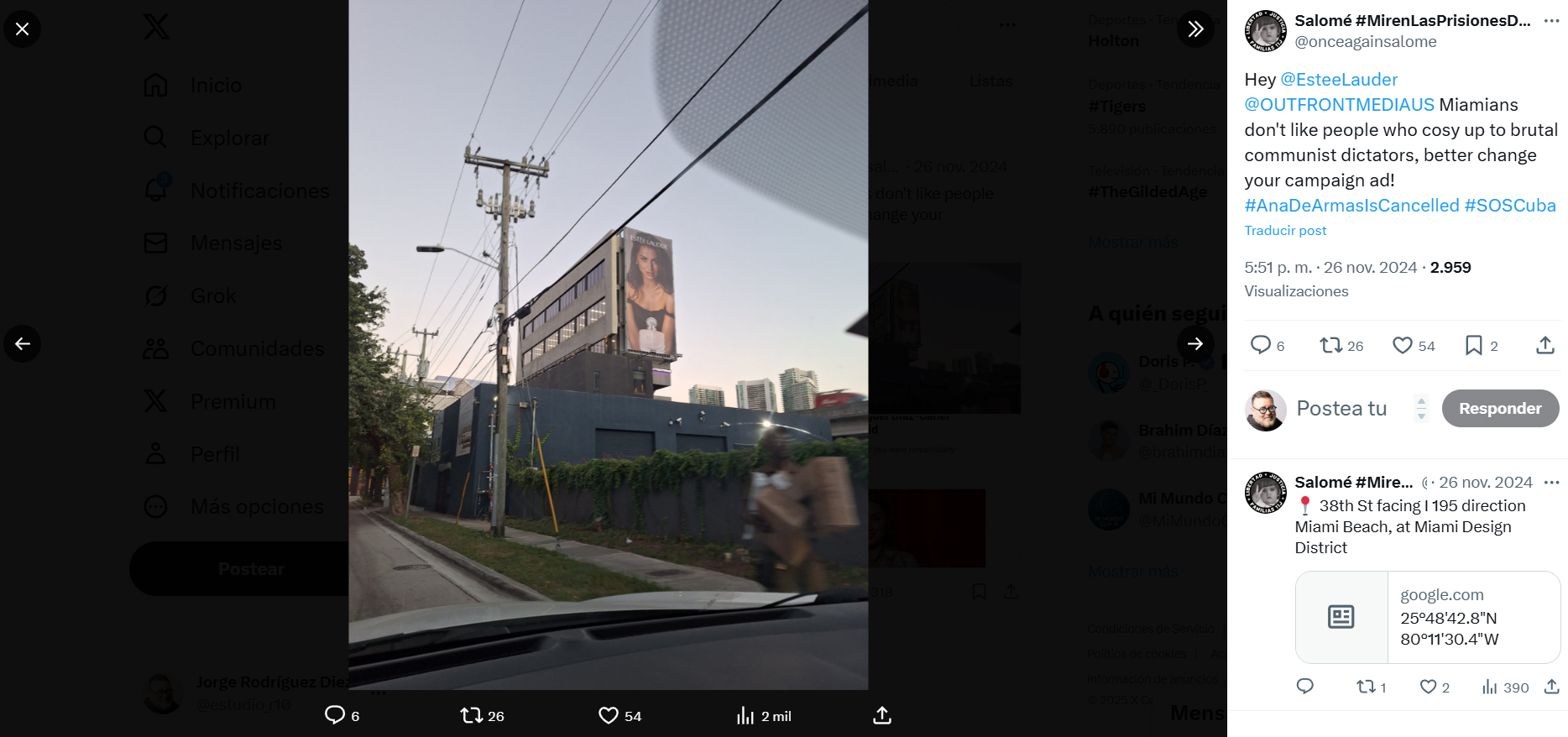

And so it serves me yet again the image of Ana de Armas brazenly overlooking the city of Miami. This time in an Estée Lauder ad, a billboard, according to the post’s author, “on a highway in Miami.” The phrase grates on my ear, almost imperceptibly but insistently. Around here we speak of avenues, streets, expressways. We speak with awe of the I‑95, the Palmetto, the Turnpike. We suffer the US1, Calle Ocho—those.

The author of the tweet cannot believe she is up there again, high above us—physically and symbolically—insulting us all. The comments are exactly what you would expect. Every flavor. From the combative, calling for a boycott of Estée Lauder, to those who doubt that a New York–based multinational would bow to pressure from a South Florida enclave, whose influence has long been concentrated in Miami, Hialeah, and Kendall. This group is, unmistakably, Cuban. And yes, for a long time it was perhaps the most politically and economically powerful community in the region.

My sense is that this is no longer the case. Hispanics of every origin and color have poured in. Above all, Venezuelans with money—middle- and upper‑class émigrés. From Cuba, meanwhile, though they keep arriving by the millions, they no longer bring the money or the distinction once tied to their old social strata. For decades our classes have been reduced to the fat and the thin. We all arrived as Republicans, radical anti‑communists, dispensing Christian blessings.

Estée Lauder billboard in Miami. 38th St., facing I‑195 toward Miami Beach, at the Miami Design District.

Back to the billboard—the one that lit the fuse. It is Estée Lauder: an American multinational founded in 1946 in New York by Estée and Joseph Lauder, specializing in skin care, makeup, perfume, and hair products. Headquarters: the General Motors Building in Midtown Manhattan. What do they sell? Advanced Night Repair Synchronized Multi‑Recovery Complex, an anti‑aging serum: $85 for a 1‑oz (30 ml) bottle. Double Wear Stay‑in‑Place Foundation: around $52. Revitalizing Supreme+ Youth Power Crème: $125. Expensive products, far from “popular.”

Their target? First and foremost, Americans with middle and high incomes. Then China, where the brand’s growth is most explosive—yes, a communist and repressive country. For them they’ve crafted tailored campaigns, hired local influencers, flooded WeChat and Tmall to hook those upper‑middle‑class kids. Third, Western Europe—France, Germany, the UK—people willing to pay for quality. Fourth, voilà le gâteau: Latin America, in this order—Mexico, Brazil, Chile. Then the Middle East, the Emirates, those who will pay handsomely for anything. And near the end, for reasons I can’t quite grasp, Japan, South Korea, and Australia.

Local political squabbles? Estée Lauder couldn’t care less. They care about what we all care about: money. If a footballer is accused of rape and convicted, no matter how many goals he scores, he’s out. A crime that ugly is a stain no brand wants. But when a famous young woman, an adult, decides to walk her dog and carry a handbag on the arm of another young man in a clean shirt… to the average earthling, she has committed no crime. A huge portion of the world neither understands nor wishes to understand—nor wants to be distracted with the detail—that her purse is paid for by the hardship of an entire people. That is the wretched reality.

Try explaining the implications of this little stroll to a young, comfortable couple in Manhattan: that he is the bloody stepson of the modafuca, and they’ll reply—“And who’s that? A rumbero? The guy who invented the mojito? Some trumpet player from Sãlsa?” Things the average gringo vaguely associates with Cuba. The older ones, maybe; the younger don’t even know Cuba exists.

That Hola managed to catch Julieta a second time, stepping out of El Corte Inglés alongside her Alpha Romeo—a flesh‑and‑blood Romeo radiating alpha bravado—a department store, not even a luxury boutique—teaches us something: Ana doesn’t care about the uproar, however loudly it’s been relayed to her. And the other? He has spent most of his life under suspicion; consequences don’t faze him. Which leaves us with another lesson: Ana’s fortune will let her live without working, in her palace, for the rest of her life—even if Estée Lauder, Louis Vuitton, and Hollywood all slam the panic button and decide to cancel her. An unlikely scenario, given two simultaneous truths: cancel culture itself is being canceled, and high‑end brands pay little heed to the cries of immigrant communities whose average incomes are modest and who don’t spend thousands on handbags.

For too long—since Martí and through Fidel Castro—we’ve convinced ourselves that Cuba was some kind of political Bermuda Triangle where great empires came to sink. It has waged a war with the United States for sixty years, and the U.S., with saltpeter bombs and cold fronts, has leveled all its cities. Cuba is fading, as is the influence of its communities. The twenty‑first century has rolled right over us while we obsess over surviving, paying bills, hunting for a pound of brown sugar, worrying over parole papers and I‑220As, enduring blackouts and that common, exhausted question: How much longer can this go on?

From where I stand, we are in no position to wage war on the multinationals of the very country we hope to be good citizens of. Blonde is still on Netflix. They haven’t pulled it. They haven’t issued an apology. And they won’t.

Personally, though, I commit to this: I will never again in my life buy a $5,000 Louis Vuitton bag. I will not purchase a single Estée Lauder product. And when Ana de Armas shoots the sequel to Blonde, I will not watch it in full—only in pieces. I might even cancel Netflix if things get too tight. Because when I come home after nine hours on the tarmac, what I crave is a good fight with communism, at least until two or three in the morning while the churrasco cools on my plate.

Estée Lauder advertisement.

Comments powered by Talkyard.