Day after day, I browse through a handful of publications that, either in their entirety or in their cultural sections, comment on the most significant events within the visual arts. They form the main source of my modest archives. At times I come across striking images that merely illustrate an article; fortunately, when the magazine is a serious one, the caption provides all the essential data. Yet beyond the excellence of the work itself, it’s worth asking, every so often, whether—as illustration—it’s truly a fitting choice.

There are moments of alignment, when it seems as if the universe is sending us a sign. Vain hope. One could say the same of crossing a disciplined line of ants at work, each keeping perfect distance from the other—and all it would mean is that they are carrying organic matter back to the nest.

Last week I came across this image in nearly every major newspaper I usually consult. The moment I first saw it, I saved it immediately—not only because it gave me a sense of quiet delight, but also because it seemed perfectly suited for this very section. When it began multiplying across the media, I imagined the exhilaration must have been universal. Most readers, I suspect, felt a similar surge of joy.

This image seized my attention at once. I suppose it was conceived—or chosen—precisely to provoke that effect on a massive scale. Within the advancing ranks of women soldiers of the People’s Liberation Army of China, one face stands out: the second from left to right. Is it mere chance?

God knows why I tend to read the BBC’s digital edition late at night. Perhaps because I enjoy — and at the same time, not entirely — its concise and direct style. It does, however, offer compelling articles on themes or events that larger media outlets often overlook. Georgina Rannard, for instance, published a captivating piece (in its English version) about the ancient practice of tattooing on the Siberian steppe.

At barely twenty‑two, the dazzling Sofia was already under Paramount’s watchful eye. Its executives, captivated by her performances in Aida (1953) and The Gold of Naples (1953), saw in her the natural successor to the great European figures Hollywood had once embraced: Ingrid Bergman and Marlene Dietrich.

According to various sources, Girl with a Pearl Earring (2003), directed by Peter Webber and starring Scarlett Johansson as Griet, offers a carefully crafted fictional account inspired by the iconic painting of the same name by Johannes Vermeer. Critics agree that the film successfully evokes the visual world of the Dutch master with notable sensitivity. Based on the novel by Tracy Chevalier, the story is set in 17th-century Delft and follows a young maid who becomes a quiet yet pivotal presence in the painter’s studio.

I believe it has something to do with age—the way we begin to reject an overwhelming percentage of the stimuli we receive each day. Visual, auditory, olfactory... perhaps only the tactile ones survive, and even then, just barely. Maybe it’s because, after fifty, we’re simply not touched as often as we once were.

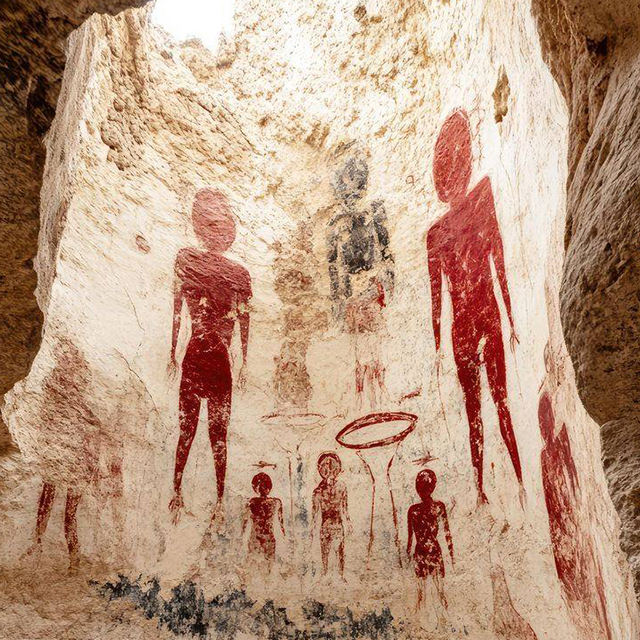

Alone in the vastness of space, that is. And many of us, alas, in the cramped solitude of our own rooms. Perhaps that is why I tend to raise an eyebrow —the left one— whenever I come across posts whose authors claim to detect, in ancient structures, rock art, or oral legends, undeniable evidence of extraterrestrial encounters at the dawn of time.