Just nine days ago, on Friday, June 20, photographer Nick Hedges passed away at the age of 81. He lived his life with the firm belief that photography is a powerful tool for driving social change. He wasn’t alone in this conviction—and speaking for myself, someone who only shoots with a phone, I’m beginning to take that idea seriously.

What do we see in the photograph—what is it, in fact, that the curator, the writer, the director of the MEP, and the readers of these reflections want to see? The image—taken by Janine in Vitry, in 1965—functions as a diptych that articulates two registers: one intimate, the other collective...

The last of these posts was published on June 7. More than two weeks without writing a single line. On my wall, yes—of course—because what I tend to write there is mostly about lived experience: the emotions they provoke, and the sediment they leave behind. A release, nothing more. Nothing to analyze.

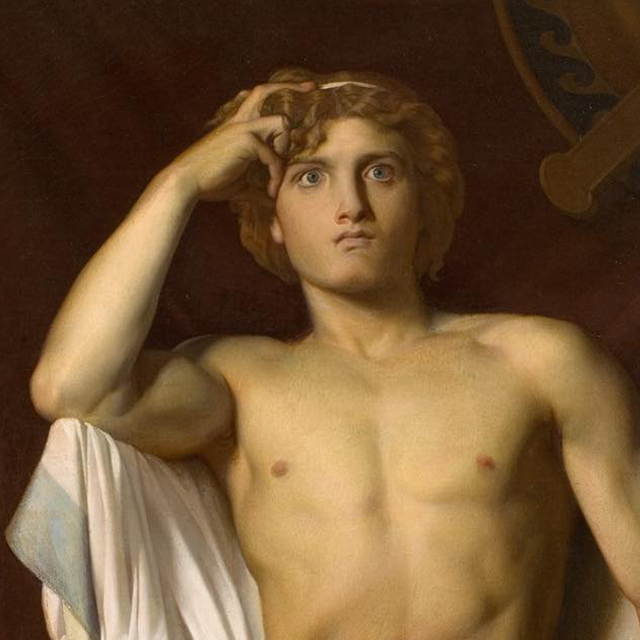

While writing the previous chronicle, I took a few pauses to search for depictions of Achilles in the history of art. To my surprise, they are scarce—and rather anemic. The balance between his weight in the collective imagination and his trace in the visual arts is tenuous, almost absurd.

Years before immersing myself in Luis Segalá y Estalella’s Spanish rendering of the Iliad, I had already been moved by the exquisite summary José Martí wrote for La Edad de Oro. Its simplicity, its scandalous beauty, is devastating.

For several years now we have lived a large part of our lives on social networks. I would say we devote almost as much attention to them as to our most intimate emotional surroundings. Almost all of us are hooked—nearly addicted. These networks seem designed to trigger some reward system in the brain, releasing a quick shot of dopamine each time we receive the tribe’s approval. It’s a flash of instant gratification that urges us to keep typing, and at the same time keeps us staring at the screen when that approval doesn’t come. That’s on one side.

This photograph could have been taken by anyone. Close enough and with a camera in hand, it was only a matter of waiting for the moment. Does that mean, then, that with a decent camera we can walk out into the street, start shooting, and challenge the legacy of a Cartier‑Bresson, to name an example? Possible, yes—yet improbable. Cartier‑Bresson defined what we now understand as the capture of the decisive moment. His immortality rests on hundreds of photographs—almost all of them flawless—where the magic of that instant manifested before his eyes, camera poised. Far too many times for it to be mere chance.

Don’t bother. There was neither a penultimate nor a last. That story was a lyrical invention by James Fenimore Cooper to captivate the eager readers of the early nineteenth century. The tribe, much diminished—now part of the Stockbridge‑Munsee—lives today in Wisconsin, to the west of the Great Lakes, enduring the heavy snowfalls the region bestows for much of the year. And what do they do? They run casinos, persistently demand the restitution of their lands, and in their spare time, pass on their culture to the new generations.

Here we see a Victorian couple upon a tandem bicycle. These nineteenth‑century contraptions were designed for two or more riders. Both were expected to pedal in unison, though the one seated at the front—promptly styled the “captain”—was entrusted not only with steering the machine but also with directing household finances and, by extension, what was eaten, when sleep was taken, and at what hour the day was to begin. The rider behind—known as the stoker—supplied power to the pedals. In other words, the one who truly set the contraption in motion, despite its ostensible purpose of shared effort.